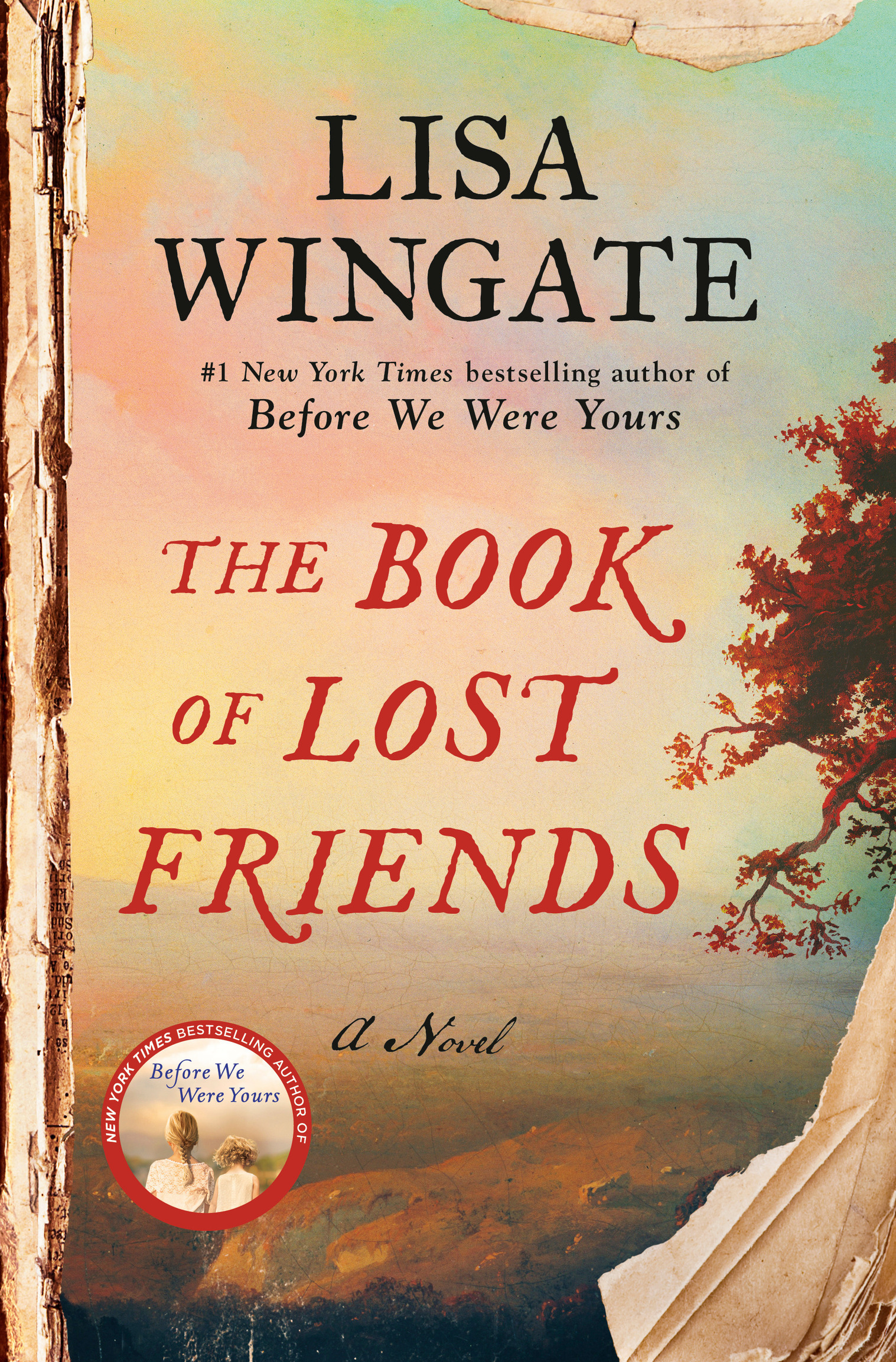

The Book of Lost Friends: A Novel

Read The Book of Lost Friends: A Novel Online

Authors: Lisa Wingate

The Book of Lost Friends

is a work of fiction. All incidents and dialogue, and all characters with the exception of some well-known historical figures, are products of the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Where real-life historical persons appear, the situations, incidents, and dialogues concerning those persons are entirely fictional and are not intended to depict actual events or to change the entirely fictional nature of the work. In all other respects, any resemblance to persons living or dead is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2020 by Wingate Media LLC

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

B

ALLANTINE

and the

H

OUSE

colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wingate, Lisa, author. Title: The book of lost friends : a novel / Lisa Wingate.

Description: First edition. | New York : Ballantine Books, 2020 | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019051637 (print) | LCCN 2019051638 (ebook) | ISBN 9781984819888 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781984819895 (ebook)

Subjects: GSAFD: Historical fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3573.I53165 B66 2020 (print) | LCC PS3573.I53165 (ebook) | DDC 813/.54—dc23

LC record available at

https://lccn.loc.gov/2019051637

Hardback ISBN 9781984819888

International Edition ISBN 9780593237724

Ebook ISBN 9781984819895

Book design by Andrea Lau, adapted for ebook

Cover design: Ella Laytham

Cover images: Dallas Museum of Art, Texas, gift of A. H. Belo Corporation/Bridgeman Images (landscape); Pobytov/Getty Images (tree); LiliGraphie/Getty Images, da-kuk/Getty Images (paper textures)

ep_prh_5.5.0_c0_r0

A single ladybug lands featherlight on the teacher’s finger, clings there, a living gemstone. A ruby with polka dots and legs. Before a slight breeze beckons the visitor away, an old children’s rhyme sifts through the teacher’s mind.

Ladybug, ladybug, fly away home,

Your house is on fire, and your children are gone.

The words leave a murky shadow as the teacher touches a student’s shoulder, feels the damp warmth beneath the girl’s roughly woven calico dress. The hand-stitched neckline hangs askew over smooth amber-brown skin, the garment a little too large for the girl inside it. A single puffy scar protrudes from one loosely buttoned cuff. The teacher wonders briefly about its cause, resists allowing her mind to speculate.

What would be the point?

she thinks.

We all have scars.

She glances around the makeshift gathering place under the trees, the rough slabwood benches crowded with girls on the verge of womanhood, boys seeking to step into the world of men. Leaning over crooked tables littered with nib pens, blotters, and inkwells, they read their papers, mouthing the words, intent upon the important task ahead.

All except this one girl.

“Fully prepared?” the teacher inquires, her head angling toward the girl’s work. “You’ve practiced reading it aloud?”

“I can’t do it.” The girl sags, defeated in her own mind. “Not…not with

these

people looking on.” Her young face casts miserably toward the onlookers who have gathered at the fringes of the open-air classroom—moneyed men in well-fitting suits and women in expensive dresses, petulantly waving off the afternoon heat with printed handbills and paper fans left over from the morning’s fiery political speeches.

“You never know what you can do until you try,” the teacher advises. Oh, how familiar that girlish insecurity is. Not so many years ago, the teacher

was

this girl. Uncertain of herself, overcome with fear. Paralyzed, really.

“I

can’t,

” the girl moans, clutching her stomach.

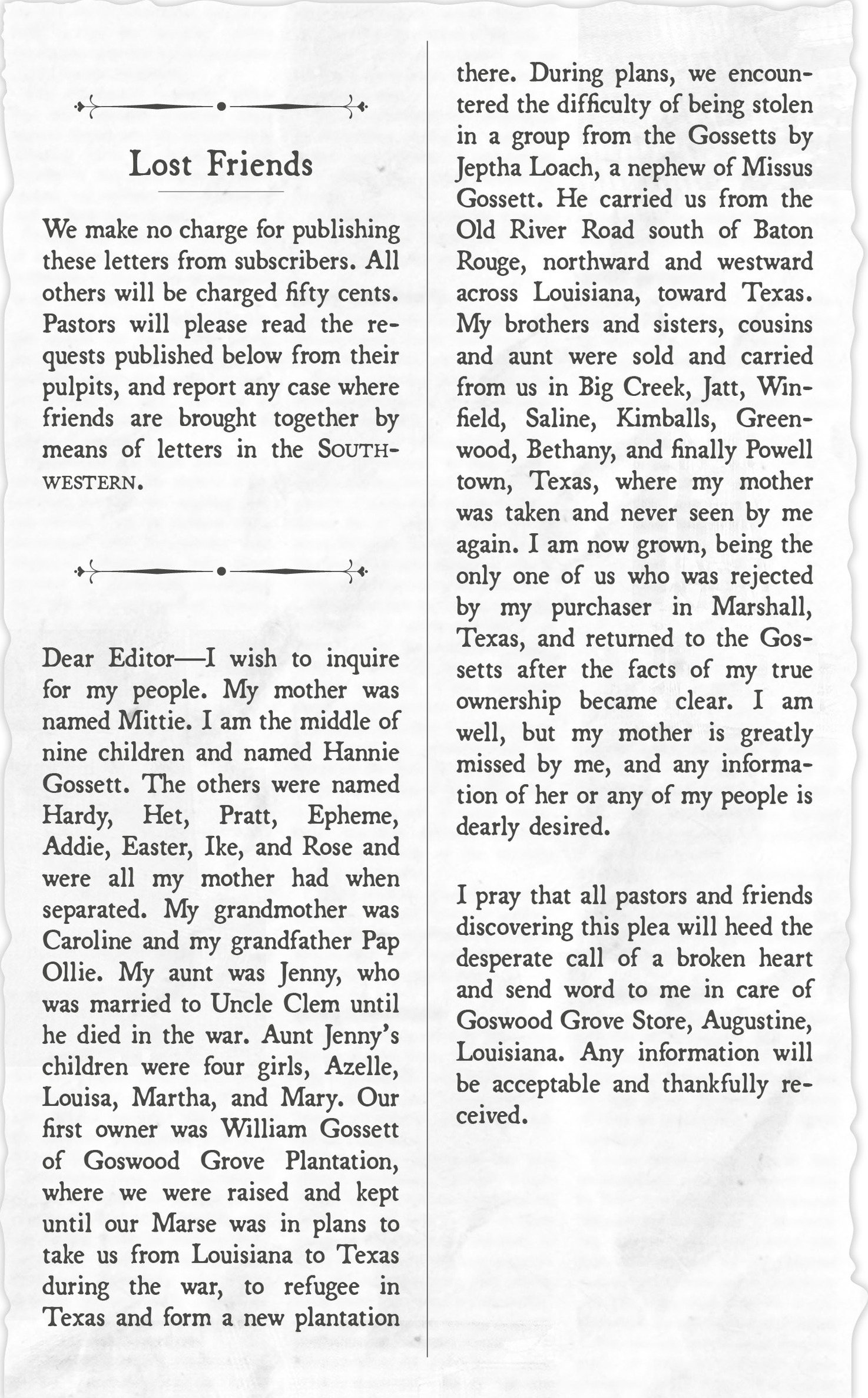

Bundling cumbersome skirts and petticoats to keep them from the dust, the teacher lowers herself to catch the girl’s gaze. “Where will they hear the story if not from you—the story of being stolen away from family? Of writing an advertisement seeking any word of loved ones, and hoping to save up the fifty cents to have it printed in the

Southwestern

paper, so that it might travel through all the nearby states and territories? How will they understand the desperate need to finally know,

Are my people out there, somewhere?

”

The girl’s thin shoulders lift, then wilt. “These folks ain’t here because they care what I’ve got to say. It won’t change anything.”

“Perhaps it will. The most important endeavors require a risk.” The teacher understands this all too well. Someday, she, too, must strike off on a similar journey, one that involves a risk.

Today, however, is for her students and for the “Lost Friends” column of the

Southwestern Christian Advocate

newspaper, and for all it represents. “At the very least, we must tell our stories, mustn’t we? Speak the names? You know, there is an old proverb that says, ‘We die once when the last breath leaves our bodies. We die a second time when the last person speaks our name.’ The first death is beyond our control, but the second one we can strive to prevent.”

“If you say so,” the girl acquiesces, tenuously drawing a breath. “But I best do it right off, so I don’t lose my nerve. Can I go on and give my reading before the rest?”

The teacher nods. “If you start, I’m certain the others will know to follow.” Stepping back, she surveys the remainder of her group.

All the stories here,

she thinks.

People separated by impossible distance, by human fallacy, by cruelty. Enduring the terrible torture of not knowing.

And though she’d rather not—she’d give anything if not—she imagines her own scar. One hidden beneath the skin where no one else can see it. She thinks of her own lost love, out there. Somewhere. Who knows where?

A murmur of thinly veiled impatience stirs among the audience as the girl rises and proceeds along the aisle between the benches, her posture stiffening to a strangely regal bearing. The frenzied motion of paper fans ceases and fluttering handbills go silent when she turns to speak her piece, looking neither left nor right.

“I…” her voice falters. Rimming the crowd with her gaze, she clenches and unclenches her fingers, clutching thick folds of the blue-and-white calico dress. Time seems to hover then, like the ladybug deciding whether it will land or fly on.

Finally, the girl’s chin rises with stalwart determination. Her voice carries past the students to the audience, demanding attention as she speaks a name that will not be silenced on this day. “I am Hannie Gossett.”

HANNIE GOSSETT—LOUISIANA, 1875

The dream takes me from quiet sleep, same way it’s done many a time, sweeps me up like dust. Away I float, a dozen years to the past, and sift from a body that’s almost a woman’s into a little-girl shape only six years old. Though I don’t want to, I see what my little-girl eyes saw then.

I see buyers gather in the trader’s yard as I peek through the gaps in the stockade log fence. I stand in winter-cold dirt tramped by so many feet before my own two. Big feet like Mama’s and small feet like mine and tiny feet like Mary Angel’s. Heels and toes that’s left dents in the wet ground.

How many others been here before me?

I wonder.

How many with hearts rattlin’ and muscles knotted up, but with no place to run?

Might be a hundred hundreds. Heels by the doubles and toes by the tens. Can’t count high as that. I just turned from five years old to six a few months back. It’s Feb’ary right now, a word I can’t say right, ever. My mouth twists up and makes

Feb-ba-ba-ba-bary,

like a sheep. My brothers and sisters’ve always pestered me hard over it, all eight, even the ones that’s younger. Usually, we’d tussle if Mama was off at work with the field gangs or gone to the spinnin’ house, cording wool and weaving the homespun.

Our slabwood cabin would rock and rattle till finally somebody fell out the door or the window and went to howlin’. That’d bring Ol’ Tati, cane switch ready, and her saying, “Gonna give you a breshin’ with this switch if you don’t shesh now.” She’d swat butts and legs, just play-like, and we’d scamper one over top the other like baby goats scooting through the gate. We’d crawl up under them beds and try to hide, knees and elbows poking everywhere.

Can’t do that no more. All my mama’s children been carried off one by one and two by two. Aunt Jenny Angel and three of her four girls, gone, too. Sold away in trader yards like this one, from south Louisiana almost to Texas. My mind works hard to keep account of where all we been, our numbers dwindling by the day, as we tramp behind Jep Loach’s wagon, slave chains pulling the grown folk by the wrist, and us children left with no other choice but to follow on.

But the nights been worst of all. We just hope Jep Loach falls to sleep quick from whiskey and the day’s travel. It’s when he don’t that the bad things happen—to Mama and Aunt Jenny both, and now just to Mama, with Aunt Jenny sold off. Only Mama and me left now. Us two and Aunt Jenny’s baby girl, li’l Mary Angel.

Every chance there is, Mama says them words in my ear—who’s been carried away from us, and what’s the names of the buyers that took them from the auction block and where’re they gone to. We start with Aunt Jenny, her three oldest girls. Then come my brothers and sisters, oldest to youngest,

Hardy at Big Creek, to a man name LeBas from Woodville. Het at Jatt carried off by a man name Palmer from Big Woods….

Prat, Epheme, Addie, Easter, Ike, and Baby Rose,

tore from my mama’s arms in a place called Bethany. Baby Rose wailed and Mama fought and begged and said, “We gotta be kept as one. The baby ain’t weaned! Baby ain’t…”

It shames me now, but I clung on Mama’s skirts and cried, “Mama, no! Mama, no! Don’t!” My body shook and my mind ran wild circles. I was afraid they’d take my mama, too, and it’d be just me and little cousin Mary Angel left when the wagon rolled on.

Jep Loach means to put all us in his pocket before he’s done, but he sells just one or two at each place, so’s to get out quick. Says his uncle give him the permissions for all this, but that ain’t true. Old Marse and Old Missus meant for him to do what folks all over south Louisiana been doing since the Yankee gunboats pushed on upriver from New Orleans—take their slaves west so the Federals can’t set us free. Go refugee on the Gossett land in Texas till the war is over. That’s why they sent us with Jep Loach, but he’s stole us away, instead.

“Marse Gossett gonna come for us soon’s he learns of bein’ crossed by Jep Loach,” Mama’s promised over and over. “Won’t matter about Jep bein’ nephew to Old Missus then. Marse gonna send Jep off to the army for the warfaring then. Only reason Jep ain’t wearin’ that gray uniform a’ready is Marse been paying Jep’s way out. This be the end of that, and all us be shed of Jep for good. You wait and see. And that’s why we chant the names, so’s we know where to gather the lost when Old Marse comes. You put it deep in your rememberings, so’s you can tell it if you’re the one gets found first.”

But now hope comes as thin as the winter light through them East Texas piney woods, as I squat inside that log pen in the trader’s yard. Just Mama and me and Mary Angel here, and one goes today. One, at least. More coins in the pocket, and whoever don’t get sold tramps on with Jep Loach’s wagon. He’ll hit the liquor right off, happy he got away with it one more time, thieving from his own kin. All Old Missus’s people—all the Loach family—just bad apples, but Jep is the rottenest, worse as Old Missus, herself. She’s the devil, and he is, too.

“Come ’way from there, Hannie,” Mama tells me. “Come here, close.”

Of a sudden, the door’s open, and a man’s got Mary Angel’s little arm, and Mama clings on, tears making a flood river while she whispers to the trader’s man, who’s big as a mountain and dark as a deer’s eye, “We ain’t his. We been stole away from Marse William Gossett of Goswood Grove plantation, down by the River Road south from Baton Rouge. We been carried off. We…been…we…”

She goes to her knees, folds over Mary Angel like she’d take that baby girl up inside of her if she could. “Please. Please! My sister, Jenny, been sold by this man already. And all her children but this li’l one, and all my children ’cept my Hannie. Fetch us last three out together. Fetch us out, all three. Tell your marse this baby girl, she sickly. Say we gotta be sold off in one lot. All three together. Have mercy. Please! Tell your marse we been stole from Marse William Gossett at Goswood Grove, down off the River Road. We stole property. We been

stole.

”

The man’s groan comes old and tired. “Can’t do nothin’. Can’t nobody do nothin’ ’bout it all. You just make it go hard on the child. You just make it go hard. Two gotta go today. In two dif’ernt lots. One at a time.”

“No.” Mama’s eyes close hard, then open again. She looks up at the man, coughs out words and tears and spit all together. “Tell my marse William Gossett—when he comes here seeking after us—at least give word of where we gone to. Name who carries us away and where they strikes off for. Old Marse Gossett’s gonna find us, take us to refugee in Texas, all us together.”

The man don’t answer, and Mama turns to Mary Angel, slips out a scrap of brown homespun cut from the hem of Aunt Jenny Angel’s heavy winter petticoat while we camped with the wagon. By their own hands, Mama and Aunt Jenny Angel made fifteen tiny poke sacks, hung with jute strings they stole out of the wagon.

Inside each bag went three blue glass beads off the string Grandmama always kept special. Them beads was her most precious thing, come all the way from Africa.

That where my grandmama and grandpoppy’s cotched from.

She’d tell that tale by the tallow candle on winter nights, all us gathered round her lap in that ring of light. Then she’d share about Africa, where our people been before here. Where they was queens and princes.

Blue mean all us walk in the true way. The fam’ly be loyal, each to the other, always and ever,

she’d say, and then her eyes would gather at the corners and she’d take out that string of beads and let all us pass it in the circle, hold its weight in our hands. Feel a tiny piece of that far-off place…and the meanin’ of blue.

Three beads been made ready to go with my li’l cousin, now.

Mama holds tight to Mary Angel’s chin. “This a promise.” Mama tucks that pouch down Mary Angel’s dress and ties the strings round a skinny little baby neck that’s still too small for the head on it. “You hold it close by, li’l pea. If that’s the only thing you do, you keep it. This the sign of your people. We lay our eyes on each other again in this life, no matter how long it be from now, this how we, each of us, knows the other one. If long time pass, and you get up big, by the beads we still gonna know you. Listen at me. You hear Aunt Mittie, now?” She makes a motion with her hands. A needle and thread. Beads on a string. “We put this string back together someday, all us. In this world, God willing, or in the next.”

Li’l Mary Angel don’t nod nor blink nor speak. Used to, she’d chatter the ears off your head, but not no more. A big ol’ tear spills down her brown skin as the man carries her out the door, her arms and legs stiff as a carved wood doll’s.

Time jumps round then. Don’t know how, but I’m back at the wall, watching betwixt the logs while Mary Angel gets brung ’cross the yard. Her little brown shoes dangle in the air, same brogans all us got in our Christmas boxes just two month ago, special made right there on Goswood by Uncle Ira, who kept the tanner shop, and mended the harness, and sewed up all them new Christmas shoes.

I think of him and home while I watch Mary Angel’s little shoes up on the auction block. Cold wind snakes over her skinny legs when her dress gets pulled up and the man says she’s got good, straight knees. Mama just weeps. But somebody’s got to listen for who takes Mary Angel. Somebody’s got to add her to the chant.

So, I do.

Seems like just a minute goes by before a big hand circles my arm, and it’s me getting dragged ’cross the floor. My shoulder wrenches loose with a pop. The heels of my Christmas shoes furrow the dirt like plow blades.

“No! Mama! Help me!” My blood runs wild. I fight and scream, catch Mama’s arm, and she catches mine.

Don’t let go,

my eyes tell hers. Of a sudden, I understand the big man’s words and how come they broke Mama down.

Two gotta go today.

In two dif’ernt lots. One at a time.

This is the day the worse happens. Last day for me and Mama. Two gets sold here and one goes on with Jep Loach, to get sold at the next place down the road. My stomach heaves and burns in my throat, but ain’t nothing there to retch up. I make water down my leg, and it fills up my shoe and soaks over to the dirt.

“Please! Please! Us two, together!” Mama begs.

The man kicks her hard, and our hands rip apart at the weave. Mama’s head hits the logs, and she crumples in the little dents from all them other feet, her face quiet like she’s gone asleep. A tiny brown poke dangles in her hand. Three blue beads roll loose in the dust.

“You give me any trouble, and I’ll shoot her dead where she lies.” The voice runs over me on spider legs. Ain’t the trader’s man that’s got me. It’s Jep Loach. I ain’t being carried to the block. I’m being took to the devil wagon. I’m the one he means to sell at the someplace farther on.

I tear loose, try to run back to Mama, but my knees go soft as wet grass. I topple and stretch my fingers toward the beads, toward my mother.

“Mama! Mama!” I scream and scream and scream….

It’s my own voice that wakes me from the dream of that terrible day, just like always. I hear the sound of the scream, feel the raw of it in my throat. I come to, fighting off Jep Loach’s big hands and crying out for the mother I ain’t laid eyes on in twelve years now, since I was a six-year-old child.

“Mama! Mama! Mama!” The word spills from me three times more, travels out ’cross the night-quiet fields of Goswood Grove before I clamp my mouth closed and look back over my shoulder toward the sharecrop cabin, hoping they didn’t hear me. No sense to wake everybody with my sleep-wanderings. Hard day’s work ahead for me and Ol’ Tati and what’s left of the stray young ones she’s raised these long years since the war was over and we had no mamas or papas to claim us.

Of all my brothers and sisters, of all my family stole away by Jep Loach, I was the only one Marse Gossett got back, and that was just by luck when folks at the next auction sale figured out I was stole property and called the sheriff to hold me until Marse could come. With the war on, and folks running everywhere to get away from it, and us trying to scratch a living from the wild Texas land, there wasn’t any going back to look for the rest. I was a child with nobody of my own when the Federal soldiers finally made their way to our refugee place in Texas and forced the Gossetts to read the free papers out loud and say the war was over, even in Texas. Slaves could go where they pleased, now.

Old Missus warned all us we wouldn’t make it five miles before we starved or got killed by road agents or scalped by Indians, and she hoped we did, if we’d be ungrateful and foolish enough to do such a thing as leave. With the war over, there wasn’t no more need to refugee in Texas, and we’d best come back to Louisiana with her and Marse Gossett—who we was now to call

Mister,

not

Marse,

so’s not to bring down the wrath of Federal soldiers who’d be crawling over everything like lice for a while yet. Back on the old place at Goswood Grove, we would at least have Old

Mister

and Missus to keep us safe and fed and put clothes on our miserable bodies.

“Now, you young children have no choice in the matter,” she told the ones of us with no folk. “You are in our charge, and of course we will give you the benefit of transporting you away from this godforsaken Texas wilderness, back to Goswood Grove until you are of age or a parent comes to claim you.”

Much as I hated Old Missus and working in the house as keeper and plaything to Little Missy Lavinia, who was a trial of her own, I rested in the promise Mama had spoke just two years before at the trader’s yard. She’d come to find me, soon’s she could. She’d find all us, and we’d string Grandmama’s beads together again.

And so I was biddable but also restless with hope. It was the restless part that spurred me to wander at night, that conjured evil dreams of Jep Loach, and watching my people get stole away, and seeing Mama laid out on the floor of the trader’s pen. Dead, for all I could know then.

For all I still

do

know.

I look down and see that I been walking in my sleep again. I’m standing out on the old cutoff pecan stump. A field of fresh soil spreads out, the season’s new-planted crop still too wispy and fine to cover it. Moon ribbons fall over the row tips, so the land is a giant loom, the warp threads strung but waiting on the weaving woman to slide the shuttle back and forth, back and forth, making cloth the way the women slaves did before the war. Spinning houses sit empty now that store-bought calico comes cheap from mills in the North. But back in the old days when I was a little child, it was card the cotton, card the wool. Spin a broach of thread every night after tromping in from the field. That was Mama’s life at Goswood Grove. Had to be or she’d have Old Missus to deal with.