The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty (61 page)

Read The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty Online

Authors: Caroline Alexander

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Military, #Naval

BOOK: The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty

5.44Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

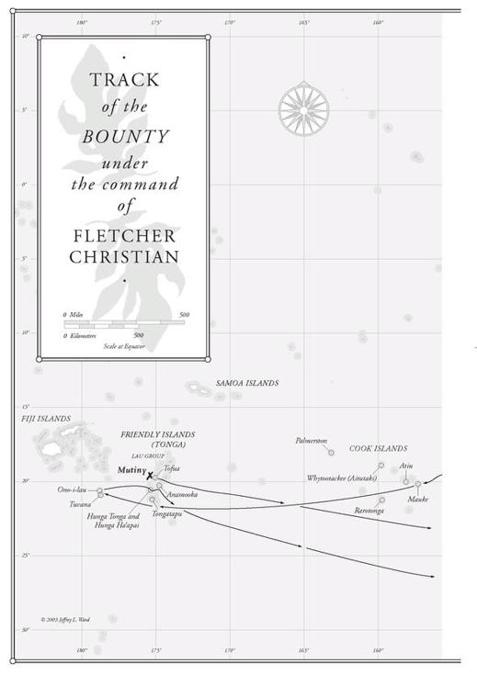

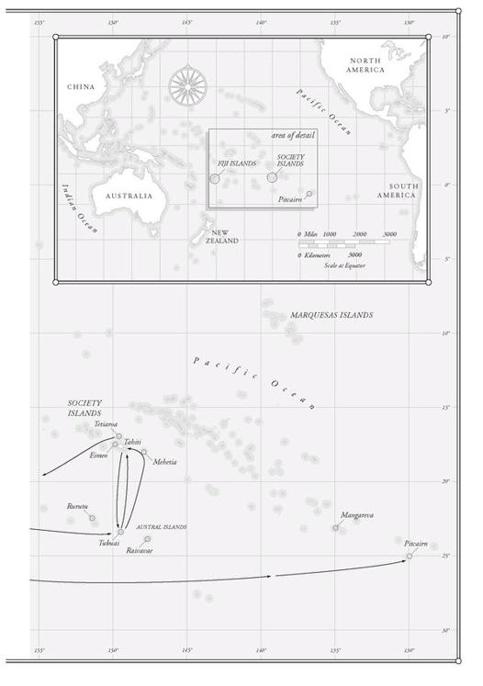

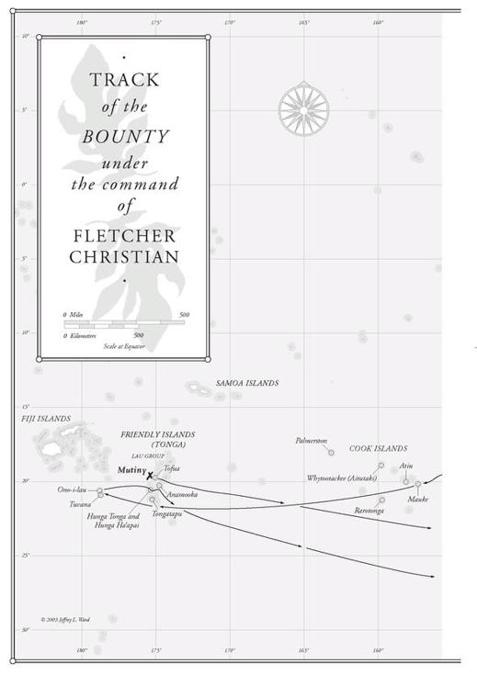

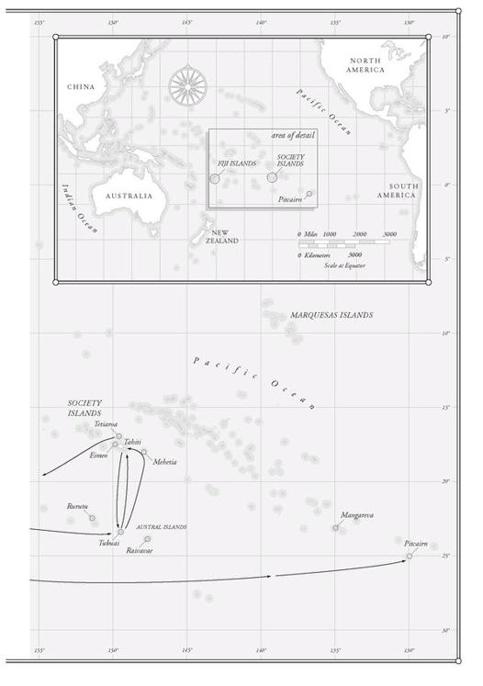

According to Adams, once the

Bounty

departed Tahiti for the third and final time, following the failed settlement and bloodshed in Tubuai, there was no definite destination. The Marquesas Islands were first discussed, but Christian, availing himself of the volumes of voyages of discovery in Bligh’s library, read Captain Carteret’s description of Pitcairn. The island was very remote, uninhabited and devoid of anchorage, ensuring that a passing ship would be less inclined to loiter; and so it was there he had steered the

Bounty

’s course.

Bounty

departed Tahiti for the third and final time, following the failed settlement and bloodshed in Tubuai, there was no definite destination. The Marquesas Islands were first discussed, but Christian, availing himself of the volumes of voyages of discovery in Bligh’s library, read Captain Carteret’s description of Pitcairn. The island was very remote, uninhabited and devoid of anchorage, ensuring that a passing ship would be less inclined to loiter; and so it was there he had steered the

Bounty

’s course.

On arrival, Christian and a reconnaissance party went ashore and returned greatly satisfied. They had found wood, water, fruit trees and rich soil. They had also discovered a mountainous and difficult land with narrow, easily defensible passes and a number of caves; the island was the perfect outlaw’s redoubt. (Christian had returned to the ship with “a joyful expression such as we had not seen on him for a long time past,” Adams told a later visitor.) The ship was slowly unloaded and then burned. While the settlement was being built, the mutineers lived under the

Bounty

’s sails; and when these were no longer required for shelter, the cloth had been cut up to fashion clothes. Thus had this small ship served her company to the very end. Her guns and anchors were observed by later visitors to be lying in the shallow water of Bounty Bay.

Bounty

’s sails; and when these were no longer required for shelter, the cloth had been cut up to fashion clothes. Thus had this small ship served her company to the very end. Her guns and anchors were observed by later visitors to be lying in the shallow water of Bounty Bay.

The massacre of the mutineers and the blacks had taken place in several waves of violence, and principally arose from the fact that the Englishmen had come to regard their Otaheitean friends as slaves. Fletcher Christian was killed in the first wave as he tilled his yam field. McCoy

and Mills heard his groans, but decided it was Christian’s wife calling him to dinner.

and Mills heard his groans, but decided it was Christian’s wife calling him to dinner.

“Thus fell a man, who, from being the reputed ringleader of the mutiny, has obtained an unenviable celebrity,” wrote Beechey, adding by way of another of his editorials, “and whose crime may perhaps be considered as in some degree palliated, by the tyranny which led to its commission.”

Captain Beechey and the

Blossom

departed Pitcairn on December 20, 1825, continuing on their own voyage of discovery throughout the Pacific and Bering Strait, as part of the Admiralty’s new polar ventures. The

Blossom

did not return to England until 1828. The full import of this voyage would be made manifest two years later.

Blossom

departed Pitcairn on December 20, 1825, continuing on their own voyage of discovery throughout the Pacific and Bering Strait, as part of the Admiralty’s new polar ventures. The

Blossom

did not return to England until 1828. The full import of this voyage would be made manifest two years later.

One of the items of interest that Beechey brought away on the

Blossom

was the diary of Edward Young, one of the most enigmatic of the mutineers. The journal, which Young started toward the end of 1793, some two months after the death of Christian in the first wave of massacres—in some accounts—was said by Beechey to give evidence of Young’s education and “serious turn of mind.” His journal, which was never to be seen or cited again, opened a window on a dark, largely undisclosed aspect of island life—the unhappiness of the island’s women. Only one of the female pioneers—Teehuteatuaonoa, nicknamed Jenny—ever gave her own version of the early days of settlement, and that only after she had escaped from Pitcairn—she had hitched a passage with Captain Reynolds on the

Sultan,

some years before, in 1817. From Young’s and Teehuteatuaonoa’s accounts, and the occasional incautious remark of John Adams, a more complete and complicated history of this exemplary community emerged.

Blossom

was the diary of Edward Young, one of the most enigmatic of the mutineers. The journal, which Young started toward the end of 1793, some two months after the death of Christian in the first wave of massacres—in some accounts—was said by Beechey to give evidence of Young’s education and “serious turn of mind.” His journal, which was never to be seen or cited again, opened a window on a dark, largely undisclosed aspect of island life—the unhappiness of the island’s women. Only one of the female pioneers—Teehuteatuaonoa, nicknamed Jenny—ever gave her own version of the early days of settlement, and that only after she had escaped from Pitcairn—she had hitched a passage with Captain Reynolds on the

Sultan,

some years before, in 1817. From Young’s and Teehuteatuaonoa’s accounts, and the occasional incautious remark of John Adams, a more complete and complicated history of this exemplary community emerged.

With the exception of the female companions of Christian and Quintal, and Jenny herself who had once been the “wife” of Adams, all the women brought to Pitcairn had been kidnapped. When the

Bounty

had arrived at Matavai Bay on its final visit, the usual friendly visitors came on board, including eighteen women, one with a child. After the women went below for supper, Christian ordered the anchor cable cut. Although told that the ship was only going around the island, the women realized the truth when they passed through and beyond the reef; one courageous woman had dived overboard. After this, Christian had been careful not to bring the ship too close to other landfalls, knowing, as Jenny said, that several of the women would have tried to swim to shore. Off the island of Eimeo, five or six leagues from Tahiti, six of the women “who were rather ancient” and presumably deemed physically unattractive were sent ashore.

Bounty

had arrived at Matavai Bay on its final visit, the usual friendly visitors came on board, including eighteen women, one with a child. After the women went below for supper, Christian ordered the anchor cable cut. Although told that the ship was only going around the island, the women realized the truth when they passed through and beyond the reef; one courageous woman had dived overboard. After this, Christian had been careful not to bring the ship too close to other landfalls, knowing, as Jenny said, that several of the women would have tried to swim to shore. Off the island of Eimeo, five or six leagues from Tahiti, six of the women “who were rather ancient” and presumably deemed physically unattractive were sent ashore.

After scouting several islands, Christian set out for Pitcairn, a search during which two full months would pass without seeing land. During this time, “all on board were much discouraged: they therefore thought of returning to Otaheite.” But at last, on the evening of January 15, 1790, the island was seen rising like a great rock from the ocean. For three days a fierce wind held them at bay, preventing any landing; that the island was so effectively defended by the elements may have been seen as a favorable omen.

With the aid of a raft, the men methodically unloaded the

Bounty,

and when everything had been removed they debated what to do with the ship. “Christian wished to save her for awhile,” Jenny said, but while they were debating, Matthew Quintal had gone on board and set a fire in the bow; later, two others followed and fired other parts of the ship. But during the night “all were in tears at seeing her in flames. Some regretted exceedingly that they had not confined Capt. Bligh and returned to their native country, instead of acting as they had done.”

Bounty,

and when everything had been removed they debated what to do with the ship. “Christian wished to save her for awhile,” Jenny said, but while they were debating, Matthew Quintal had gone on board and set a fire in the bow; later, two others followed and fired other parts of the ship. But during the night “all were in tears at seeing her in flames. Some regretted exceedingly that they had not confined Capt. Bligh and returned to their native country, instead of acting as they had done.”

Prisoners now of the island, the women set to work. It would be their skills of homemaking, their knowledge of preparing the familiar fruits and fish and fowl, and their traditions of making bark cloth and clothes that would carry the settlement. Passed around from one “husband” to the other, as men died and the balance of power shifted, they rebelled.

“[S]ince the massacre, it has been the desire of the greater part of them to get some conveyance, to enable them to leave the island,” Edward Young recorded in his diary. Shortly before, he had come upon Jenny handling the skull of Jack Williams and learned to his amazement and horror that the women had refused to bury the slaughtered men.

“I thought that if the girls did not agree to give up the heads of the five white men in a peaceable manner, they ought to be taken by force, and buried,” wrote Young indignantly; he was after all a gentleman. One of these unburied skulls belonged to Fletcher Christian, whose head, according to Jenny, had been “disfigured” with an axe after he was killed.

The women’s desperation finally prompted the men to build them a small boat, according to Young, who also reported that Jenny in her zeal had ripped boards out of her own house for building material. On August 13, 1794, the little vessel was completed, and two days later launched. But the women’s hopes of a return to their native land were bitterly dashed when the vessel foundered, “according to expectation,” as Young wrote, with masculine amusement. Miserably, the women returned to their captors. The “wives” of McCoy and Quintal—who, as Beechey had to comment, “appear to have been of very quarrelsome dispositions”—were frequently beaten.

A grave was duly dug for the murdered men’s bones. Three months later “a conspiracy of the women to kill the white men in their sleep was discovered.” No punishment was inflicted, but as Young recorded, “We did not forget their conduct; and it was agreed among us, that the first female who misbehaved should be put to death.” And so the years passed. A multitude of offspring were born to the women, who had been passed promiscuously around the male survivors. Jenny herself had formerly been the “wife” of John Adams, who as Alexander Smith had tattooed her with his initials while they were on Tahiti. When he left her, she was turned over to Isaac Martin. With the arrival of the

Sultan

in 1817, Jenny at last made good her escape, returning in a roundabout fashion after a voyage of some years, to her native Tahiti thirty-one years after she had departed. As the newsman who first recorded her story reported, she had been “apparently a good looking woman in her time.” Her hands were hard from manual labor.

Sultan

in 1817, Jenny at last made good her escape, returning in a roundabout fashion after a voyage of some years, to her native Tahiti thirty-one years after she had departed. As the newsman who first recorded her story reported, she had been “apparently a good looking woman in her time.” Her hands were hard from manual labor.

Mauatua (Christian’s wife, known by him affectionately as Mainmast, perhaps for her height), Vahineatua, Teio (and her little daughter, Teatuahitea), Faahotu, Teraura, Obuarei, Tevarua, Toofaiti, Mareva, Tinafornea, and Jenny or Teehuteatuaonoa . . . the names of the women who made the Pitcairn experiment succeed had rarely been evoked. Also evocative were the familiar names with which Jenny referred to the

Bounty

men—Billy Brown, Jack Williams, Neddy Young, Matt Quintal—the names of English lads one might run into on any waterfront. Christian on the other hand, as Adams reported reverentially, was always addressed as “Mr. Christian.” As Lieutenant Belcher had been shrewd enough to perceive, the authority Christian possessed had held in check even those against his desperate scheme. Sleepless and the worse for drink, he seems to have succeeded with his mutiny in great part because he was the most popular man on board.

Bounty

men—Billy Brown, Jack Williams, Neddy Young, Matt Quintal—the names of English lads one might run into on any waterfront. Christian on the other hand, as Adams reported reverentially, was always addressed as “Mr. Christian.” As Lieutenant Belcher had been shrewd enough to perceive, the authority Christian possessed had held in check even those against his desperate scheme. Sleepless and the worse for drink, he seems to have succeeded with his mutiny in great part because he was the most popular man on board.

How much of his authority he retained to the end is difficult to tell. He clearly lost his grasp at Tubuai, and also the confidence of the sixteen men who at the last chose to leave him and take their chances on Tahiti. Events related by Jenny suggest that he was having difficulty holding his small band intact during the months in which they roamed the sea, seeking their new home. Adams, as often, contradicts himself: Christian “was always cheerful,” he told Beechey, and was “naturally of a happy, ingenuous disposition.” Yet, when discussing the island’s geography Adams pointed out a cave, “the intended retreat of Christian, in the event of a landing being effected by any ship sent in pursuit of him, and where he resolved to sell his life as dearly as he could.” In this cave, Adams told other ships, Christian was wont to retreat and brood. And what of Adams’s earlier statements to Captains Staines and Pipon that Christian had “by many acts of cruelty and inhumanity, brought on himself the hatred and detestation of his companions”?

Despite the heartfelt pronouncements of almost every visitor that “for good morals, politeness of behavior,” as well as their “strict adherence to the truth, and the principles of religion,” the Pitcairners had, thanks to John Adams, “not their equals to be found on earth,” it is very unclear how much of anything Adams himself said was to be taken as truth. Most suspicious were his inconsistent stories of Christian’s death. Was the story he spontaneously told Captain Folger, the first visitor to catch him unawares, the real truth? If so, then Fletcher Christian was killed in a single massacre that occurred on the island about four years after arrival. Or was the truth that which he related, after a sober second thought, to Folger’s second mate—that Christian committed suicide? Why, when Christian’s own wife was living, had Adams insisted that she had predeceased her husband? And what of his statement to Captain Pipon that the mutineers had divided into parties, “seeking every opportunity on both sides to put each other to death”? Had Adams and Christian been of the same “party”? Or had they been adversaries? What importance is to be attached to the striking fact that Adams was one of only two men left standing in the wake of the massacres? Was it Adams’s party that killed Christian? Could it even be—impossible as it would seem of the venerable patriarch! —that it was Adams who killed Christian?

With the arrival of each ship eager to pay homage to the Christian miracle of Pitcairn, the wily survivor made subtle adjustments to his narration. From the tenor of the questions he was asked, he must have soon caught hold of the shape his story had taken in England. By the 1820s, Adams had introduced a new element: the mutiny had been caused by the “remorseless severity” of Bligh, who had even subjected his mate, Fletcher Christian, “to corporal chastisement.”

Other books

Fire Inside: A Chaos Novel by Kristen Ashley

Deadly Thyme by R.L. Nolen

The Centurion's Wife by Bunn, Davis, Oke, Janette

The Zone of Interest by Martin Amis

Davo's Little Something by Robert G. Barrett

The Frenzy Way by Gregory Lamberson

Statesman by Anthony, Piers

When Seducing A Duke by Kathryn Smith