The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss (11 page)

Read The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss Online

Authors: Dennis McKenna

Dad not only greatly enjoyed flying, he was an excellent pilot known for his skill at flying in the Colorado Rockies. It was a skill worthy of recognition; flying in the high mountains is tricky and dangerous, given the changeable weather, unpredictable winds, and other hazards. Dad was often called out by the local Civil Air Patrol to search for some plane that had gone down in the mountains. Most of these crashes were caused by ignorance, bad judgment, or inexperience on the part of pilots my father called “flatland furriners” with no business flying in that rugged terrain. In most cases he was right. He flew for years in the mountains, under some pretty harrowing conditions, and never had any problems. He had good judgment and knew when not to push it.

My father spent years sharing a Piper Cub with the other members of a local flying club before he got his Tri-Pacer. I mentioned how he used his plane to cover his vast sales territory, which he enjoyed. The plane also gave him more time with us in Paonia, which on balance was probably a good thing though it increased the opportunities for conflict. Wings certainly gave us options that weren’t available to other families, like weekend trips. We could take off for the Grand Canyon, Mesa Verde, Carlsbad Caverns, or Arches National Monument and be back home in time for school on Monday morning. It was great fun, and I think it broadened our perspective beyond that of most of our peers. In the summer of 1962, when I was eleven and Terry was fifteen, my father borrowed a somewhat bigger plane, a Piper Comanche, and took us on a two-week trip to the Seattle World’s Fair, an amazing experience for both of us. The theme of the fair, Century 21, was a paean to the utopian,

Jetsons

-style future that supposedly lay just a few short decades ahead. For two geeky boys who were already steeped in science fiction and popular science, to tour that world was a thrill.

My most memorable flying experiences took place closer to home. My father had a friend who had a ranch farther up the Crystal River valley from the one owned by my aunt and uncle. He also owned a small plane and had built a rough dirt airstrip on his land beside some of the river’s best fishing spots. My father had permission to fly in and catch a few fish whenever he wanted. It became a regular thing for the two of us to get up early in the morning, fly over, and return in time for breakfast with a mess of fresh trout to fill out the menu.

This was an incredibly cool thing to do, but also tricky! Getting in and out of that airstrip required every bit of Dad’s skill as a pilot, due to the updrafts and downdrafts he had to contend with. Once you came over the ridge on the way in, you had to drop like a stone in order to lose enough altitude to make a run at the strip; and you only got one chance. He had to put the plane into what felt like a suicide dive, only pulling up at the last minute to make a perfect landing. Flying out was similar. When taking off in the thin mountain air, the danger was that we wouldn’t have the lift to clear the ridge. As soon as we left the ground, Dad had to put the plane into a steep climb and risk stalling, in order to avoid the downdrafts from the winds that were howling over the ridge. If we didn’t make the altitude on the first try, there was no going back; we’d end up as a crumbled piece of tinfoil on the unforgiving rocks below.

I didn’t realize at the time that we were taking a significant risk every time we made that trip. Dad must have known, but I did not. I never worried for a minute about the danger. My dad, my amazing father, the legendary mountain pilot, was at the controls, and there was simply no way we were going down. It couldn’t happen, and it didn’t. He was that good. I was that naive. Looking back on these experiences, I think we both must have been a little nuts to have attempted them.

If you were a kid growing up in Western Colorado in the 1950s and ’60s, “huntin’ and fishin’ ” were just things you did. They were pretty much in your blood. Except when they weren’t, which was the case with me. Our father was an excellent fly fisherman. I tried to learn to fly fish, but I was lousy at it. I could never get the hang of casting the fly into the right ripple in the stream where the fish were lurking, let alone to know, as he did, they’d be there. On the rare occasions when I did catch something, I’d have to kill it, usually by beating its head against the nearest rock. I didn’t like killing fish; it was the most distasteful part of the whole exercise. I got pretty good at cleaning them, but I didn’t care for that either, especially the part where I had to remove the fish shit from their intestinal tract, located just below the spinal column. Yuck! So I never really made the cut as a fisherman, much to our father’s disappointment, I’m sure. Later, our outings got better once he’d abandoned any expectation that I’d actually fish. Instead he’d fish, and I’d go off somewhere, smoke a little weed, and hunt mushrooms. By then I’d developed a passion for hunting mushrooms, and I had a pretty good eye. I was always looking for the Holy Grail, in the form of

Amanita muscaria

, but they were rare. I did find plenty of delicious edibles, though, and enjoyed many a feast.

I was only a little more successful at hunting than fishing. I had a .410 shotgun inherited from my great grandfather, a beautiful gun that fired a single shell, handcrafted for his wife when he was stationed at a military post in South Africa. Or so went the family legend, which may or may not have been true. Dad had a bigger gun, a 12-gauge double-barrel. Shooting ducks and pheasants wasn’t that hard, and I regularly brought them down. But as with the fish, you then had to clean them, a messy business neither of us liked; we were always trying to give away our kill to friends. I’m sorry to admit it, but the pleasure for us was in the hunt.

Hunting elk and deer was a more serious business, not least because we used high-powered rifles, and you could get yourself seriously killed if you weren’t careful. Shotguns could be just as dangerous, of course, but they lacked the aura of lethality that rifles had. Also, hunting large animals was more associated with the whole manhood thing. It was a shamanic activity, a rite of passage. Somewhere in all manly men (and manly men we were, or at least wanted to be) there is a Paleolithic warrior lusting to take spear in hand and head out on the ice sheet in search of saber-toothed cats. We were living out that primal quest, reconnecting with our hunter-shaman selves, albeit with better technology. That included the car ride we’d take every fall to stage our reenactment at Lee Sperry’s ranch on West Muddy Creek.

Lee was a real cowboy, a cattleman who operated an enormous ranch with several thousand head. Every hunting season, he opened the place to tourist hunters from Texas, mostly, but also my father and his friends. For two weeks we lived there in a caveman’s paradise, surrounded by a testosterone-drenched, stinking, grizzled bunch that drank hard liquor and communicated in grunts. In reality, of course, these folks (with the exception of Lee, who was as tough as he looked) were soft tenderfoots—accountants and salesmen, teachers and grocers, mostly sedentary and well padded. But for two weeks we were the fucking Clan of the Cave Bear. I recall it as a fantastic experience, though much of it I disliked. I was afraid of the horses we had to ride; I didn’t enjoy getting up in the cold at four in the morning, breaking the ice in the watering trough in the early dawn; I didn’t want to spend all day on the trail getting my ass rubbed raw, freezing most of the time, then getting sunburned and eaten by bugs, before dragging back, dog-tired, at day’s end. It was terrible. It was wonderful! These were some of the richest experiences I ever shared with my Dad. I never complained or whined, because real men don’t whine, and I wanted more than anything to be accepted as part of the clan.

Dad and his friends were looking to bag elk. Hunting for deer was beneath them; deer were for tourists and wimps (and children, like me). Elk were big and dangerous, a fitting prey for manly men, and besides, you got a lot more meat when you brought one down. And bringing one down was a big deal. For one thing, it meant that the hunt was probably over for the day, because you had to gut and haul the animal, sometimes in pieces, back to the curing house at the ranch. Elk are huge animals that easily weigh 500 pounds. It took several men to hoist one up in a tree using a block and tackle slung over a limb. The next step was to slit the animal’s throat and let the blood drain, then cut open the body and remove the viscera. After cutting the skin at certain places, we’d peel it back to reveal the muscles and tendons. To call this “dressing” the animal struck me as odd, because what we were actually doing was undressing it. After that, the smaller carcasses could be loaded on a packhorse and carted back to the ranch. The bigger ones had to be cut in half and loaded on two horses—a grisly, bloody, smelly mess.

Back at the curing house, we’d hoist the dead creature on hooks, and there it would hang for up to two weeks. What was known as “curing” really amounted to rotting; but it did seem to tenderize the meat and improve its flavor. Uncured meat had a “gamey” taste that made it less appealing. Frankly, it always tasted pretty gamey to me, but I learned to like it at least enough to eat it. Once cured, the carcass went to Chapman’s Storage Lockers, where it was cut into pieces with band saws and other tools and stored. That was our meat for the winter. At home, we had elk steaks every Saturday night for the next six months whether we wanted them or not, and believe me, at the end of six months, you didn’t want them. What I would have done by then for a nice beef burger or a piece of fried chicken! Sometimes I’d complain that the meat was tough, and my father would respond with a standard retort: “It’s a lot tougher when there isn’t any!” Hard to argue with that.

I took part in the annual hunt for a few years, until I was twelve or thirteen. Terence had gone through the same initiation, but the two of us never had a chance to partake in that rite together. By the time I was old enough to go, Terence had lost interest, or had already left for California, where he spent his last two years of high school.

The truth is I was no better at hunting than I was at fishing, so I never ended up killing anything. Or almost never. Which was fine by me. Despite the discomforts, I enjoyed riding horses all day through the aspen forests of the high country. At that time of the year, the aspens were putting on their brightest colors, blinding yellows and oranges in great swaths as far as the eye could see. The air was crisp and tangy, just cold enough so you could see your breath; the sky was a robin-egg blue, as blue as it gets. The West Muddy was a beautiful place to be that time of year; bagging an elk or deer, fulfilling the mission to actually kill something, seemed like an afterthought.

Eventually, on what must have been my third or fourth trip, I did succeed in killing my first and only deer, a nice-looking four-point buck. I was with Dad when I spotted it, in a little glen down the ridge, standing in a cluster of aspen trees, sixty or seventy yards away. Dad spotted it at the same time, and instructed me to get off the horse quietly, crouch down, and take my time aiming. By the time I had, the thing had disappeared before my eyes, as if it had melted back into the trees. But I went ahead and took aim at the spot where it had been a moment before. I squeezed off a shot, more or less blindly. And as blind luck would have it, the deer had not moved; my aim was true. It was a clean shot to the neck, and the thing flopped down.

Leading our horses, we walked slowly down the ridge to where the animal lay, still breathing but obviously near death. Dad unsheathed his hunting knife, walked up and slit its throat to end its suffering. I felt no joy at witnessing this, no sense of triumph, no sense of pride. At that moment, I didn’t feel anything like a manly man. I felt like a murderer; I had killed something beautiful and wild and free. But I could not show this emotion to my Dad, or to the other men who by then were approaching. I bit my lip to keep from crying, pulled myself together, and began the grim task of skinning the creature I had slain.

That was the last time I went hunting with our father on the West Muddy. I had undergone the rite of passage. I was now officially a member of the clan, a manly man among manly men. And that was enough. I have to admit I felt a touch of pride, though not for a killing a deer; I felt only nauseated and weak-kneed about that. No, the pride was in knowing that I had made my father proud. Together we had shown his peers, now my peers, that I wasn’t just some geeky weirdo four-eyed gawky kid. I could be a brute with the best of them. In that weird, twisted, uniquely male world where killing something is seen as a good thing, I had risen to the occasion. The values of the clan were again affirmed.

Chapter 9 - Goodbye to All That

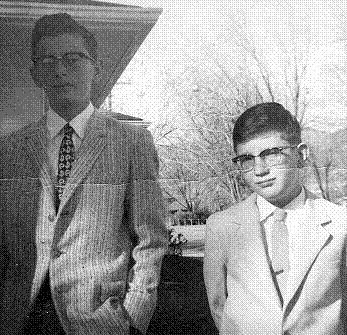

Terence and Dennis dressed for church, 1959.

So this was the picture of our family life at the end of the 1950s, pulled from memory like a faded snapshot from those innocent years. For me, it evokes the breathless moment of eerie calm that settles over the landscape before a summer thunderstorm; nothing is happening, yet the air is charged with anticipation. There was a foreboding intuition that the old order, the old certainties, would soon be swept away. Despite an apparent calm, social forces beyond anyone’s control were massing on the horizon, ready to rip the idyllic Norman Rockwell fantasy to shreds. Indeed, everything we thought we knew, everything we thought we were, would soon be transfigured by the winds of change.