The Burning Shore (13 page)

Authors: Ed Offley

No. O.I.C./S.I./57

U-BOAT SITUATION

Week ending [January 12, 1942]

The general situation is now somewhat clearer and the most striking feature is a heavy concentration [of U-boats] off the North American seaboard from New York to Cape Race. Two groups have so far been formed. One, of 6 U-boats, is already in position off Cape Race and St. John’s [Newfoundland], and a second, of 5 U-boats, is apparently approaching the American coast between New York and Portland [Maine]. It is known that [there are] a total of 21 boats [heading west]

.

9

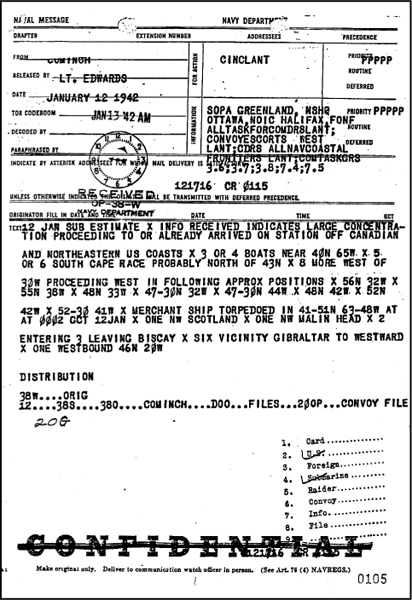

Less than ten hours later, a second, direct message from COMINCH to all major American and Canadian naval units in the Atlantic rocketed into the ESF code room, giving the latitude-longitude locations of the U-boats:

INFO RECEIVED INDICATES LARGE [U-BOAT] CONCENTRATION PROCEEDING TO OR ALREADY ARRIVED ON STATION OFF CANADIAN AND NORTHEASTERN US COASTS X 3 OR 4 BOATS NEAR 40N 65W X 5 OR 6 SOUTH [OF] CAPE RACE PROBABLY NORTH OF 43N X 8 MORE WEST OF 30W PROCEEDING WEST IN FOLLOWING APPROX POSITIONS X 56 N 32W X 55N 38W X 48N 33W 47–30N 32W X 47–30N 44W X 48N 42W X 52N 42W X 52–30N 41W.

10

Hours after British intelligence pinpointed the location of a dozen U-boats heading to the American coast to attack shipping, the Operational Intelligence Centre flashed the information to US Navy Headquarters, which then, in the early hours of January 13, 1942, transmitted this message warning the US Atlantic Fleet (CINCLANT) and all other naval units on the East Coast. Despite more than twenty-four hours’ advance warning of the U-boats’ arrival offshore, the navy did nothing to thwart the attack. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION.

For Admiral Andrews, the nightmare now loomed before him. The U-boats were just hours away from unleashing a full-scale offensive against the Eastern Sea Frontier. Unlike the hapless Admiral Husband Kimmel at Pearl Harbor, who saw his fleet half disarmed in a surprise attack that came as a genuine bolt from the blue, here was a clear and explicit tactical warning that gave the numbers, locations, and anticipated timing of Admiral Dönitz’s planned Drumbeat offensive. Yet Andrews could do absolutely nothing about it.

There was, however, something that Admiral Ingersoll at Atlantic Fleet Headquarters in Norfolk or Admiral King at Main Navy in Washington could do: as the U-boats crept in toward their attack positions late in the day on January 12, the nineteen combat-ready destroyers then resting in East Coast ports were readily available to take on the advancing U-boats. It would have been a simple and straightforward mission for the Atlantic Fleet to carry out: surge the destroyers out to sea to mount a search-and-destroy operation against the advancing wolf pack. Yet, inexplicably, King and Ingersoll did nothing. They had assembled the destroyers and other warships to escort a large troop convoy mustering in New York and destined for Northern Ireland. Since the deployment of American soldiers to Iceland and the British Isles was a top priority of the Arcadia Conference still underway in Washington, DC, neither admiral was inclined to delay its departure, even in the face of the imminent U-boat threat.

11

A

T 2000 HOURS

EWT

ON

T

UESDAY

, J

ANUARY

13, 1942, the

USS Gwin

was at sea in the western Atlantic approximately twenty-five

nautical miles south of Newport, Rhode Island. The 347-foot

Gleaves

-class destroyer, just two days shy of its first anniversary as a commissioned US Navy warship, had left Boston earlier that afternoon for an overnight passage to the naval anchorage at Staten Island, New York.

Gwin

was a heavily armed warship, with five 5-inch/.38-cal. dual-purpose guns; six 20-mm antiaircraft guns, ten 21-inch torpedo tubes, and a full complement of depth charges. Having emerged from the Cape Cod Canal at 1713 hours EWT, Commander J. M. Higgins and his crew of fifteen officers and 260 enlisted men were holding steady on a west-southwest course that would skirt the southern coastline of Long Island as they proceeded at a leisurely speed of just eleven knots. Unbeknownst to the 276 American sailors, a fierce new chapter in the Battle of the Atlantic was about to erupt very close by.

At that same hour, U-123 was forty nautical miles south of the

Gwin

. Just fifty-four hours after sinking the freighter

Cyclops

, Kapitänleutnant Reinhard Hardegen and his fifty-one-man crew were also heading for New York. U-123 still had fourteen torpedoes aboard, and by order of Vice Admiral Dönitz, Hardegen’s initial attack area consisted of the coastal waters off Long Island and the approaches to New York Harbor. Though neither knew it, Commander Higgins and Kapitänleutnant Hardegen were sailing on a parallel course—the Americans heading to a brief in-port visit and the Germans on their way to battle.

12

Shortly after midnight local time on Wednesday, January 14, one of Hardegen’s lookouts spotted the moving lights of an Allied merchant ship at about 4,400 yards to port ahead of the U-boat, moving on a reciprocal course before vanishing in a fogbank. As

the ship emerged from the fog, looming up to port, Hardegen ordered all four bow tubes flooded, and several minutes later Hoffmann hit the firing lever to send a pair of G7es racing off toward the target just nine hundred yards away.

The 9,577-ton Panamanian oil tanker

Norness

was carrying a cargo of 12,200 tons of fuel oil to Liverpool when Hardegen pounced. The first torpedo from U-123 missed, but the second in the salvo struck the tanker on its port side near the stern, blasting a giant hole in the hull and sending a massive shower of fuel oil that covered the tanker’s main deck. Although the explosion created a 150-foot column of flames and thick smoke, and fuel covered the tanker’s deck and superstructure, the ship itself did not immediately catch fire. Nevertheless, the

Norness

was doomed. As the ship began listing to one side, its masts toppling onto the main deck, Captain Harold Hansen raced up to the bridge, only to be warned by a lookout that a German U-boat was visible off to port. Fearing a second torpedo might ignite the fuel into a major conflagration, Hanson ordered his forty-man crew to abandon ship. One crewman had already perished when the torpedo detonation blew him over the side into the frigid ocean, and a second man drowned when a lifeboat capsized, throwing him into the water. Twenty-five individuals made it safely into a second lifeboat, and six more escaped on a life raft. Hansen and seven others then successfully lowered the ship’s only motorboat, but when they cast off, its engine would not start. In desperation, the eight survivors hand-paddled away from the sinking

Norness

. Nine minutes later, a second torpedo crashed into the tanker directly beneath its bridge, setting off another towering smoke column.

The

Norness

had been able to transmit an emergency radio message at the beginning of Hardegen’s attack, but no US Navy warships scrambled from port to hunt for the U-boat lurking offshore. Twenty-seven minutes after firing the first of four torpedoes at the tanker—two of which missed—Hardegen ordered a fifth torpedo launched, and this finished off the

Norness

, which sank rapidly by the stern as its surviving crewmen watched from a distance.

Meanwhile, the destroyer

Gwin

continued on its leisurely westward path toward Staten Island. Whether from atmospheric interference at sea or human incompetence ashore, the tanker’s destruction went undetected for more than twelve hours until a navy ZNP dirigible spotted the tanker’s near-perpendicular bow section jutting from the water and a lifeboat with twenty-five of the thirty-nine survivors floating nearby. The dirigible’s aircrew then contacted the Newport-based destroyer

USS Ellyson

, which was underway for routine systems tests six weeks after its formal commissioning, and directed it to the site to pick up the survivors. The 165-foot-long coast guard patrol vessel

Argo

was also in the vicinity and retrieved a small number of the Norwegian crewmen, and the American fishing boat

Malvina D

later found Captain Hansen and his crewmen in the disabled motor lifeboat.

While the search-and-rescue operation proceeded southeast of Montauk Point, the US Navy on January 14 finished the final details of assembling Task Force 15 at the Brooklyn Navy Yard and its Staten Island anchorage. The task force included the battleship

USS Texas

; aircraft carrier

USS Wasp

; cruisers

USS Quincy

,

USS Wichita

, and

USS Tuscaloosa

; and eighteen frontline Atlantic Fleet destroyers, including the

Gwin

. Their mission

was to rush American soldiers to Iceland and Northern Ireland to relieve the marines on Iceland and free up British troops in both locations for redeployment to North Africa. Task Force 15 was to protect Convoy AT10, a cadre of four troopships carrying an army battalion to Iceland and 4,508 soldiers to Northern Ireland.

13

The day after the sinking of the

Norness

, on Thursday, January 15, Convoy AT10 sailed from New York and formed up at sea inside what Admiral King would call a “curtain of steel,” a cordon of all twenty-three Task Force 15 warships. Convoy AT10 would make it safely to Iceland, then Londonderry, Northern Ireland. Nevertheless, the decision to sail the troop convoy stripped the US East Coast of the last meaningful defense against the German U-boats. It was all that Dönitz could have hoped for—and more.

14

S

HORTLY BEFORE DAWN ON

T

HURSDAY

, J

ANUARY

15,

THE

same day that Task Force 15 was scheduled to leave New York, Kapitänleutnant Horst Degen ordered his control room watch-standers to blow the ballast tanks. U-701 breached the surface of the western Atlantic to find the weather still as stormy as it had been for the past six days. The southwesterly gale still blew, and the waves often topped thirty feet, causing the U-boat to pitch and roll severely each time it reached a crest, then plunged once more into the trough of the sea. Despite the rough weather, however, Degen frequently found it necessary to surface; he and his crew would endure the pounding just long enough to suck clean air into the boat and recharge the batteries before once more seeking shelter in the depths. Even for that short time, the seas were often so tumultuous that Degen dared not send the regular complement of watch officer and three lookouts to the bridge.

When he was able to man the bridge fully, Degen and his lookouts faced the nearly impossible task of searching visually for the silhouettes of Allied merchantmen and enemy warships;

the towering waves reduced visibility to a minimum. But their diligence finally paid off. Thirty minutes after surfacing at dawn on January 15, U-701’s lookouts suddenly spotted a merchant steamer ten degrees off the port bow just five nautical miles away and heading directly toward them. Since his only two remaining torpedoes were lodged in storage canisters below the exterior deck plates, Degen ordered a crash dive to avoid detection.

With no change in the weather in sight, the U-701 crewmen gritted their teeth and continued with their arduous daily routine. But elsewhere along the North Atlantic littoral, Operation Drumbeat was getting into high gear.

Another Gruppe Ziethen U-boat had already claimed the first victim in Newfoundland waters. Oberleutnant zur See Erich Topp in U-552 had been patrolling southwest of Cape Race in the late afternoon of January 14, when his lookouts sighted a midsize merchant freighter. Because of the heavy seas, Topp closed to within nine hundred yards before launching. Even so, the turbulence caused three of five torpedoes fired to miss. Nevertheless, two torpedo impacts made quick work of the 4,113-ton British freighter

Dayrose

, breaking the ship in half. Only four crewmen out of the total complement of thirty-eight aboard survived, another testament to the peril of winter in the North Atlantic. Topp dispatched a brief message to U-boat Force Headquarters reporting the kill.

Topp’s message was the first firm confirmation that the Drumbeat and Ziethen U-boats had made it to their attack areas. The BdU daily war diary noted, “It is not known whether the boats have reached their positions off the coast of USA. It is possible that they will arrive later than the estimated time because of

bad weather. U-552 reports bad weather south of Newfoundland so that boats must be having difficulty taking position, to say nothing of attack.” The uncertainty would quickly disappear as, within the next two weeks, thirteen of the U-boats from the two groups, plus three boats from the follow-on wave, broke radio silence to announce the destruction of Allied merchant ships in coastal waters from Newfoundland to Cape Hatteras.

1