The Burning Shore (24 page)

Authors: Ed Offley

For the next three days, U-701 hunted in vain for Allied merchant ships. Spotting a southbound 8,000-ton freighter after nightfall on Tuesday, June 16, Degen chased the target for several hours, approaching close enough to fire two of his G7e electric torpedoes. Both missed, and Degen abandoned the effort.

The next night, Degen moved inshore to hunt near Cape Hatteras, then shifted southwest toward Cape Lookout and entered Onslow Bay near the southern end of his designated patrol area. The boat’s four radio operators kept a twenty-four-hour watch, listening on their headphones for the distant sounds of a freighter’s propeller churning through the water. The passive sonar system could pick up propeller noises from merchant ships up to dozens of miles away and enable Degen to get a bearing on the target to begin the hunt. In the shallows off the North Carolina Outer Banks, however, excellent sound propagation and the results of earlier U-boat attacks would send U-701 sprinting miles toward a suspected target, but once there, the crew would find only shipwrecks.

Ample targets passed by during that frustrating three-day ordeal, but the belated formation of the coastal convoy system by the Atlantic Fleet and Eastern Sea Frontier had moved them beyond U-701’s reach. During that time, two coastal convoys—one northbound from Key West and another southbound from New York and Hampton Roads—passed through the Outer Banks area with a total of thirty-four merchant ships displacing 249,316 gross registered tons. Under heavy escort, the two formations rounded Cape Hatteras in daylight when U-701 was hiding on the seabed over one hundred miles to the east.

On Wednesday, June 17, Degen decided to bend BdU’s restriction on daylight operations and moved closer to shore. Instead of finding a fat merchantman, however, U-701 stumbled on a small patrol boat that quickly became a major headache. Patrolling at periscope depth at around 1000 hours, Degen spotted a small trawler heading directly toward the U-boat that then

passed by about five hundred yards away. The presence of the small warship—one of the civilian vessels converted to serve as a patrol craft in the navy’s coastal defense system—forced U-701 to cancel its daily surfacing to ventilate the boat, and conditions inside worsened.

The next day, U-701 was somewhat farther out from Cape Hatteras than on previous days, but the ubiquitous trawler made another appearance, patrolling roughly parallel to the Outer Banks. For a second day, Degen and his crew were unable to ventilate the boat. He decided that he had to take the trawler out.

2

B

Y ALL ACCOUNTS

, the patrol craft

USS YP-389

was unfit for hunting U-boats. The navy had acquired the 110-foot Boston fishing trawler on February 6, 1942, and rushed to convert it into a coastal patrol vessel. Its armament consisted of a World War I–era 3-inch/23-cal. cannon, two equally antiquated Lewis .30-cal. machine guns, and a pair of tiny depth charge racks that held two three-hundred-pound depth charges apiece. It lacked sonar and radar. Its maximum speed was just nine knots—half the top speed of a Type VIIC U-boat on the surface. Its manual steering and round-bottomed hull made maneuvering difficult at best and impossible in rough seas. Its crew consisted of three officers and twenty-one enlisted men, all naval reservists who had received scant instruction in antisubmarine warfare tactics.

After serving as an inshore patrol craft for three months, the

YP-389

received a transfer to Morehead City, North Carolina, for service along the Outer Banks.

YP-389

’s commander, Lieutenant Roderick J. Philips, requested an engine overhaul but could only

get minor repair work accomplished. Arriving at Morehead City on Tuesday, June 9, Philips learned that his vessel would be one of several small craft assigned to patrol a defensive minefield off Ocracoke Island and Cape Hatteras. Its primary duty would be to warn passing merchant ships of the danger and prevent them from getting too close to the mines.

On June 14, the

YP-389

left Morehead City on its first patrol, which passed without incident—except for the disheartening discovery that the 3-inch gun would not fire. Upon return to port, Philips had the gun inspected by a chief gunner’s mate, who concluded that it needed a new firing pin. The operations department at Morehead City ordered a replacement but rebuffed Philips’s request to remain in port until the gun was fixed. On Thursday, June 18,

YP-389

returned to Cape Hatteras lacking its most important weapon.

Shortly after midnight on Friday, June 19, U-701’s lookouts again spotted the silhouette of the small patrol craft as it proceeded southwest along the Outer Banks. As with earlier sightings, when the vessel reached a point near the Diamond Shoals light buoy, it reversed course and began heading northeast. It was the moment Degen and his crew had been waiting for. Degen quietly passed the order, and his 88-mm gun crew silently climbed up the conning tower ladder, descended to the main deck, and readied the

Schnelladekanone

for firing. At Degen’s order, U-701 slowly gained speed and closed in behind the target on its starboard quarter.

Lieutenant Philips was serving as officer of the deck in the

YP-389

’s tiny pilothouse atop the stern living quarters. His quartermaster and a signalman were also there, and two other sailors

were standing lookout. “It was a quiet night, clear, very dark at the time, the moon had gone down,” Philips later said. Then, suddenly, a hail of tracer bullets crashed into the patrol craft from about three hundred yards off.

On U-701, Degen and his lookouts watched intently as the 88-mm gun crew and two machine gunners on the bridge fired without letup into the 170-ton patrol craft. “Our gunners pumped shell after shell into that poor vessel,” Degen later recalled. “Not a single shell failed to reach its destination. Because of our ceaseless firing the cutter was almost lost within the first fifteen minutes.”

Philips did what he could to save

YP-389

, but it was hopeless from the start. He sounded general quarters, which brought the rest of the crew up on deck. The murderous gunfire instantly cut several of them down. Philips then got on his vessel’s radiotelephone and alerted the coast guard station at Ocracoke that he was under attack. The voice on the other end promised to scramble boats and aircraft, but by that time the

YP-389

was ablaze in several areas from incendiary rounds that had struck the hull and small superstructure. Two of his men were manning the .30-cal. machine guns and returning fire, but they could not see the U-boat. In desperation, Philips told his helmsman to keep the U-boat astern and raced aft to drop the patrol craft’s four depth charges in a desperate attempt to drive off the attacker. Although he succeeded in rolling them into the water, their explosions occurred too far from the U-boat to damage it or force it to give way.

When Philips saw that the U-boat had now closed to within 150 yards, he realized that the situation was hopeless and ordered

his crew over the side in lifejackets. The

YP-389

was still making nine knots, so after Philips and his men abandoned ship, the burning vessel continued for another half mile until a shell from the U-boat struck the engine room and destroyed its diesel motor.

Concerned that the flames from the burning trawler might attract aircraft or other patrol vessels, Degen ordered U-701 to break off the engagement. After an hour, the distant bloom of fire quietly went out. Three hours later, an Ocracoke patrol craft arrived on scene and picked up Philips and his men. Of the twenty-four crewmen aboard, six had been killed, and another twelve were injured.

By the time of Philips’s rescue, U-701 was well out to sea, preparing to lurk underwater for another seventeen hours. Degen was glad that he had gotten rid of the patrol craft that had caused so much nuisance but felt slightly ashamed of the brutal attack. However, his morale and that of his men soared several hours later when a message arrived from BdU reporting that the Chesapeake Bay minefield had caused the sinking of four enemy ships earlier in the week. “Congratulations to U-701,” the message continued. “Well done!”

3

D

URING THE WEEK THAT FOLLOWED

U-701’s destruction of

YP-389

, Degen boldly kept the U-boat on patrol relatively close to shore, even though the moon was waxing toward full and the danger of detection increased dramatically with each passing night.

As the days passed, Degen and his crew became frustrated by the heat, incessant aerial patrols, and absence of targets. On

Sunday, June 21, Degen spotted a formation of thirteen merchant ships in his periscope, most likely southbound Convoy KS512, but was unable to intercept it for a submerged daylight attack. The coastal convoy system was proving its effectiveness. During the week of June 19 to 26, four convoys with eighty merchant ships totaling 583,475 gross registered tons passed through U-701’s patrol area off Cape Hatteras without sustaining a single loss.

Finally, the U-boat’s luck seemed to turn. In the late afternoon of Thursday, June 25, U-701’s hydrophone operator heard the distinctive sound of a ship’s propeller churning through the water. Raising the periscope, Degen spotted the silhouette of a midsize freighter steaming north without escort within sight of the beach. He ordered his crew to battle stations and began calling off the range and bearing of the target.

The 7,256-ton Norwegian freighter

Tamesis

was carrying a cargo of 9,300 tons of copper, tin, and palm oil from Angola to New York as it headed toward Cape Hatteras. Master Even A. Bruun-Evensen would have been well aware of the risks in steaming in those dangerous waters without escort as he had passed through the area twice since the U-boats began operating off the US East Coast five months earlier. Fifty crewmen and seven passengers were aboard—and all of them, too, had doubtless heard the terrifying reports of the U-boats roaming along the North American coastline.

Shortly after 2000 Eastern War Time, a female passenger standing on the starboard bridge saw a long, black object heading for the

Tamesis

at what she described as “a rapid rate.” Before she could call out her sighting to any crewmen, the

torpedo struck the ship on its starboard side at the No. 4 hatch. The explosion threw up a tall column of water on either side of the hull. Bruun-Evensen ordered passengers and crew to abandon ship in four lifeboats. The hours passed with no follow-on attack since Degen, anxious to escape before any warships could respond, had broken off contact after the first torpedo. Early the next morning, most of the crew reboarded, and Bruun-Evensen beached the listing ship in Hatteras Inlet. The ship was later towed to New York for repairs.

Two days later, U-701 struck again. Shortly after sunrise on Saturday, June 27, Degen’s hydrophone operator picked up multiple propeller sounds. It was southbound Convoy KS514 with thirty-one merchant ships. Guarding the formation were seven warships, including the destroyer

USS Broome

and six smaller vessels. Degen ignored the threat from the escort group and closed in for a submerged attack. The formation was twenty-nine nautical miles south-southeast of Cape Hatteras when one of two torpedoes fired from U-701 struck the 6,985-ton British tanker

British Freedom

. Master Frank Morris initially ordered the fifty-five-man crew to abandon ship in three lifeboats, but after fifteen minutes, he noticed the tanker showed no sign of sinking despite a thirty-foot hole in its side. Reboarding, they restarted the ship’s engines and broke away from the convoy to return to Norfolk.

Several of the escorts, meanwhile, had rushed in to attack the U-boat. The patrol craft

USS St. Augustine

straddled U-701 with a spread of five depth charges. The shock temporarily disabled both e-motors and shattered glass instrument dials in the conning tower. Rather than attempting to finish off U-701, however, the escorts—apparently concerned that other U-boats might pounce on the formation—quickly broke off their attack to return to the merchant ships. Because of the strong escort presence, Degen decided to abandon the convoy, and his men spent several hours repairing the minor damage caused by the depth charges. They did not have to wait long for their next victim, which would turn out to be the richest prize of all thus far in their patrol.

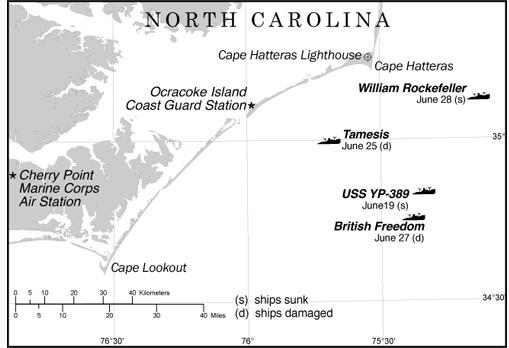

Like many U-boats, U-701 found the area east of Cape Hatteras to be a rich hunting ground for Allied merchant ships. ILLUSTRATION BY ROBERT E. PRATT.

Master William R. Stewart no doubt thought his ship was safe as it passed Diamond Shoals and headed northeast up toward Cape Hatteras at midday on Sunday, June 28. The 14,054-ton American oil tanker

William Rockefeller

was carrying a cargo of 135,000 barrels of fuel oil from Aruba to New York under a

seemingly strong escort. Upon arriving off Ocracoke Lighthouse the previous afternoon, the ship had moored for the night in the protected anchorage. When the

William Rockefeller

departed the next morning, a coast guard patrol boat escorted the tanker, and three patrol planes circled overhead. On board, a six-man Naval Armed Guard gun crew stood by a solitary 3-inch gun mounted on the stern deck. None of those defenses, however, would help in the encounter that followed.