The Burning Shore (27 page)

Authors: Ed Offley

One hour after sinking the U-boat, Kane sighted a freighter steaming about five miles away and turned toward it. Coming upon the vessel, Kane identified it as a Panamanian-flagged merchant ship. Flowers climbed up into the cockpit with a flashing light and signaled to the ship in Morse code: “Submarine sunk

in this area, survivors in the water. Please send a small boat.” The ship’s captain signaled back, “Congratulations,” but did not alter course to assist. Kane later theorized that the Panamanian skipper was fearful that other U-boats might be in the area and refused to put his ship in harm’s way.

Several minutes after receiving Flowers’s second message, Cherry Point called back and ordered Kane to repeat the details of the attack and sinking. Flowers did so as Kane turned the bomber and headed back toward the survivors. At this point, more frustration: with a sea state creating waves six to eight feet in height, Kane and his crew could not find the smoke floats or any sign of the Germans. Meanwhile, they sighted another A-29 from their squadron flying by. Flowers tried to raise the aircraft on the radio, but his transmission was blocked by a loud, continuous signal from a shore station that effectively jammed the channel. Cherry Point finally radioed Kane a second time and instructed him to send a series of bursts on a frequency of 314 kilocycles so that other aircraft could home in on his position. Nearly two hours had now passed since the sinking.

Finally, other units began to join the search. Kane and Corporal George Bellamy both sighted coast guard patrol boat

USCGC-472

, which was steaming about thirty-seven nautical miles from Cape Hatteras Lighthouse on a bearing of ninety-six degrees. Flowers used his blinking light to alert the patrol craft, and it turned to head for the sight of the sinking. Kane also heard from Cherry Point that a navy patrol plane and four more A-29s from the 396th Medium Bombardment Squadron were scrambling to join the hunt. But the sun was going down, and spots of bad weather hampered the efforts. All proved unsuccessful.

Kane made one more attempt to locate the men in the water, but the white caps flecking the ocean made it impossible to identify anything, and his fuel state was becoming critical. He finally had to break off to return to Cherry Point, landing an hour later with just five minutes’ worth of fuel in his aircraft’s last tank.

4

D

EGEN AND THE OTHER SURVIVORS

spent a long night in the water. Their plight eased somewhat when the surface of the ocean grew calm, making it less difficult to cling to the flotation gear and possible for the men to save energy. Then an hour after sunrise on Wednesday, July 8, they sighted a coast guard vessel approaching from the north. “As far as we could see, she was going to directly hit our position, but suddenly she zigzagged away and passed at a distance of about 1,000 meters,” Degen said. The cutter was close enough that the Germans could clearly see its crew on the bridge but too far away for the Americans to see or hear them. Once more the ocean had picked up, and the men were lost in the waves and white caps. It was a devastating blow to their morale, compounding the feeling of desperation that came with their increasingly sunburnt skin, their weakening physical states, and their growing hunger and thirst. Even worse, the group floated through a patch of heavy oil, which burned their mouths and nostrils when an errant wave doused them with the substance.

As the harsh summer sun climbed high in the sky, five more men in Degen’s group gave up and drowned. Others had become delirious from exposure and the lack of food or water.

An unexpected event that afternoon brought the tiniest bit of relief. One of the men spotted a lemon and a coconut floating by. Degen tore the fruit in half and passed it around. “Each man was able to suck from that sour fruit, which burned like hell in our throats, but still gave a little stimulus,” Degen said. Another crewman, Ludwig Vaupel, managed to break an opening in the coconut shell by boring two holes with a safety pin found on Degen’s clothing. Each survivor was able to swallow some of the very sour coconut milk. Then Vaupel managed to break the shell apart by striking it repeatedly against the metal oxygen flask on his

Dräger

escape lung. Each man avidly chewed on a piece of the coconut meat. This proved disastrous. Because by now the men could not breathe through their nostrils due to the saltwater irritation, they immediately gagged on the coconut pieces.

By evening, the group had dwindled to only seven men. As the darkness cloaked them for a second time, Degen quietly exhorted the others to keep warm by hugging their neighbors, massaging their limbs, and stretching muscles that ached beyond measure. Close to midnight, three more sailors gave up and slipped beneath the surface. Even those with enough physical stamina to continue hanging onto their makeshift raft found themselves hallucinating.

At sunrise on Thursday, July 9, Degen’s group was down to just four men lingering at the edge of consciousness. Only Degen, Kunert the navigator, Radioman Grotheer, and Machinist’s Mate Vaupel were left of the sixteen men who had fled through U-701’s conning tower hatch. With the rising sun once more came “a murderous heat,” Degen remembered. Although the water was again calm, during the night their circle of tied-together flotation devices had come apart, and Degen had floated some distance away from the other three. All were too far-gone to consider any attempt to reconnect.

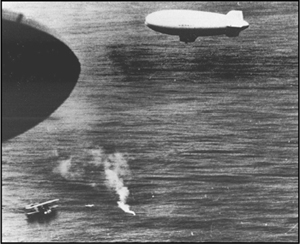

A US Navy blimp circles overhead as a coast guard PH-2 seaplane rescues the seven survivors of U-701 after their discovery on July 9, 1942. US NAVY PHOTOGRAPH.

It was midday when Herbert Grotheer heard a strange humming sound and sensed a large shadow falling across the spot where he floated on the water. He blearily opened his eyes and looked around. He saw Kunert and Vaupel slumped lifelessly in their flotation gear. Degen was several hundred feet away, barely conscious in a lifejacket. Grotheer heard the thrumming sound again and looked up. A large US Navy blimp was hovering above him. As he watched, a door to the cabin attached to the underside of the dirigible opened and a man called out, “Who are you?”

Grotheer replied in a hoarse croak, “Ich bin von einem Deutschen U-Boot.”

Crewmen from a navy amphibian aircraft pull a dazed and exhausted Bruno Faust into the plane after sighting U-701’s seven survivors on July 7, 1942. US NAVY PHOTOGRAPH.

The man disappeared inside the cabin and then returned with a second crewman. They wrestled a large shape out through the hatch. A large inflated life raft splashed down into the water. Summoning his last reserve of energy, Grotheer scrambled into the raft, followed by Kunert and Vaupel. Scarcely believing their good fortune, the three men settled down. Then the man overhead shouted again and pointed: “One man over there!” Paddling with their hands, the three Germans reached an unconscious figure kept breathing by the American life jacket that supported his head out of water. It was Degen. Once the three crewmen had managed to pull Degen into the life raft, the dirigible’s crew threw down a package containing a first aid kit, two loaves of bread, water, and canned vegetables and fruit.

Lieutenant Harry Kane points to the location of his attack on U-701 as his four air crewmen watch. From the left, Corporal George E. Bellamy, bombardier; Corporal Presley C. Broussard, flight engineer; Lieutenant Lynn A. Murray, navigator; and Corporal Leo P. Flowers, radio operator. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION.

Several hours later, a coast guard PH-2 seaplane piloted by Commander Richard L. Burke landed near the raft and picked up the four survivors. To their astonishment, three other crewmen from U-701 were already aboard. As the seaplane droned through the air toward the Norfolk Naval Air Station, the survivors exchanged accounts of what had befallen them. Gerhard Schwendel, Werner Seldte, and Bruno Faust were the only survivors from a group of about twenty crewmen who had escaped from the bow compartment through the torpedo-loading hatch. It had taken them nearly a half hour to unlock the hatch and get it completely open. By that time, the Gulf Stream had carried the conning tower group nearly a mile away, well out of eyesight

or hailing distance. The blimp had apparently come upon the second group some time before finding Degen and the three men with him. A crewman aboard the coast guard seaplane told them that when they were finally sighted forty-nine hours after Kane’s attack, they had drifted nearly 110 nautical miles northeast from the site where the U-boat had gone down.

5

For the three days that passed after the sudden sighting, attack, and destruction of U-701, Harry Kane and his aircrew resumed their regular schedule of coastal patrols, generally aware that other units were still searching for the U-boat’s surviving crewmen. Upon returning to Cherry Point on the evening of July 7, Kane became vexed, then furious, when navy and Marine Corps officials at the base at first refused to believe his account of the sinking. Given the intense rivalry between the navy and the US Army Air Forces over land-based antisubmarine patrol bombers and the fact that navy pilots had already sunk three U-boats, while the army score to date had been zero, it was not unusual that the navy pilots at Cherry Point immediately debunked Kane’s claim of a U-boat kill. “The navy was there and the navy, to my knowledge, didn’t care to say that the . . . Army Air Corps had sunk the submarine,” Kane said. “They wouldn’t believe me.”

Then on Thursday, June 11, Kane was suddenly ordered to the office of Lieutenant Colonel Monteigh.

“We’re going to Norfolk,” the squadron commander said. “We want you to go with us.”

Not knowing why, Kane and his four crewmen climbed into one of the squadron’s A-29s, with the lieutenant colonel in the pilot’s seat. Arriving at the Norfolk Naval Air Station, the army

fliers were driven to a hospital on base where they were surprised to see a number of civilians—Kane thought they were either FBI or Naval Intelligence agents—standing around with submachine guns. A small group of officials stood close by. Two of them introduced themselves to Kane and his men as Navy Secretary Frank Knox and Vice Admiral Adolphus Andrews from Eastern Sea Frontier Headquarters. They entered a large hospital bay, where Kane saw a heavily sunburned man dressed in pajamas and a hospital robe sitting in a chair. One of the officials bent over and muttered something in German to the man, who looked at Kane, then struggled painfully to his feet. He threw Kane a sharp military salute.

“Congratulations,” Horst Degen said in clear English. “Good attack.”

6

O

N

S

UNDAY

, J

ULY

12, 1942,

THREE DAYS AFTER THEIR

dramatic rescue at sea, the seven survivors of U-701 left Norfolk under armed guard for a US Army detention camp at Fort Devens, Massachusetts. For the next two months, army and navy interrogators grilled Horst Degen and his men about every aspect of their U-boat service, from their

Baubelehrung

“familiarization training” and workups in the Baltic to the boat’s three war patrols in the North Atlantic.