The Case of Lisandra P. (21 page)

Read The Case of Lisandra P. Online

Authors: Hélène Grémillon

“Vittorio is deceiving you. He told you all that because I just found out he had a mistress and he was afraid I might denounce him. Give me the photographs, I'll show her to youâit's obvious,

when you know; you see no one but herâmaybe I've been mistaken right from the start. Maybe he really did kill his wife.”

Commissioner Perez holds Eva Maria's plastic bag to one side.

“There's no point.”

“What do you mean there's no point?”

“Dr. Puig already told us about it. And that, indeed, was the last straw that drove him to share his suspicions about you with us. Just because a woman is wearing makeup, from there to assume she's a man's mistress: that is the fruit of an overactive imagination, Señora Darienzo.”

“But wait, just because he says she's not his mistress doesn't mean you have to believe him.”

“True. But rest assured, it is our job to leave nothing to chance, and we have just come from her house. She is indeed a fine-looking girl, but she is simply one of Lisandra's childhood friends, you see, hardly the stuff of novels.”

“âOne of Lisandra's childhood friends,' how convenient, Lisandra isn't around to say otherwise. And anyway, does one exclude the other? Even if she was

one of Lisandra's childhood friends

, how do you know she wasn't also Vittorio's mistress?”

“It's natural for you to project the role of a mistress onto this woman, to fantasize about another woman's status that you would like for yourself: you're jealous.”

“That's absurd! And the water from the vase? What is that supposed to mean? Don't you wonder why no flowers were found at the crime scene?”

“That is indeed the only gray area in this affair, and we have been wondering about it, but perhaps you will help us get to the bottom of it.”

“I tell you: Lisandra had a lover there that evening. Lisandra had her lovers, too.”

“We know.”

“Vittorio showed up, he surprised them, and he threw the lover and his flowers out the door; an argument broke outâyou go and see your mistress, I have the right to receive my lovers, and so on . . . It degenerated; maybe it was just an accident. But I'm convinced of it now, Vittorio really did kill his wife.”

“Interesting. But Dr. Puig has another theory. The water in the vase might be the symbol of the one element that was missing from your imagery that night: the water from the Rio de la Plata. You absolutely insist your daughter died there. It's an incoherent gesture, the poetic license of a drunken woman.”

Commissioner Perez and Lieutenant Sanchez are standing in front of Eva Maria. Suddenly, she sees them differently. What if these two used to be involved with the junta, and now they'd gone over to the police? There must be a lot of them. And what if they had planned all of this with Vittorio, of a common accordâhave her locked up, because she would not leave it alone, she was ready to testify against the former regime at any time. Lock up an innocent woman who had bad ideas and release a murderer who had good ones. The contract with Vittorio. Exchange the repositories of guilt, and in the place of murderers, lock up any remaining subversives. Same old story. But now that they couldn't do it quite so openly, they had to find a stratagem. And maybe they even planned murdersâwhat if some crimes were orchestrated to make innocent people take the blame? That way they could cover up the bad memories once and for all and stifle any gossips. Eva Maria steps closer to Commissioner Perez. She spits in his face. Lieutenant Sanchez hurries over to stop her; Commissioner Perez motions to him to stay where he is.

“Señora Darienzo, where were you on the night of August 18?”

Eva Maria doesn't reply. Commissioner Perez tries again.

“Señora Darienzo, where were you on the night of August 18?”

“Here.”

“Is there anyone who can confirm this?”

“No. I was alone.”

Estéban interrupts.

“When I came back at around three o'clock in the morning my mother was here; I checked.”

“How do you know you checked on that particular evening? I must say, only young people can claim to have such a good memory.”

“I check every evening when I come in . . . to make sure everything is all right.”

“I see. But forgive me, just because your mother was here at three o'clock in the morning doesn't mean she was here earlier that evening, at ten o'clock. The approximate time of the crime. Señora Darienzo, we must ask you to come with us. We are taking you into custody.”

Eva Maria collapses on the sofa.

“But I haven't done anything.”

The commissioner steps closer.

“Perhaps you simply don't remember. If it can help, that is Dr. Puig's theory. He thinks you were under the influence of alcohol that night. You will be able to plead attenuating circumstances.”

Suddenly Eva Maria is afraid. Afraid they might be right. Because when she drinks, she can't remember, and that is why she drinks, for the black holes that feel so good. And what if Vittorio really is convinced she is guilty? Then the keys, those keys, how would she have ended up with them in her possession? She never makes up false memories; she remembers that young manâshe may be an alcoholic but she isn't crazy, no way, not crazy. But suddenly Eva Maria is no longer sure of anything. She looks at Estéban; what if she had made it all up, and the young man in the stairs was no more than a

projection of Estéban, and the “crime of passion” was her own? But that can't be; she's not in love with Vittorio, of that she is sureâshe would know, after all. Eva Maria's gaze lands on the pile of cassettes, which Lieutenant Sanchez is putting into the big plastic bag. Eva Maria grabs the bag from him, pounces on it.

“I'll show you I wasn't in love with Vittorio. You're going to listen to my cassette, and you'll understand right away.”

Eva Maria is on her knees on the floor. Estéban goes out of the living room. Eva Maria rummages through the cassettes. Like a crazy woman.

“I don't understand . . . it was here; I saw it several times . . . I know it was here . . .”

Estéban comes back into the living room. He goes over to Eva Maria. Helps her to her feet.

“I have it. I'm sorry, Mama, I couldn't help it. I listened to it.”

Estéban has the cassette in his hands. Broken. The tape dangling, crumpled, illegible, unusable. On the side, a label: “Eva Maria.” Commissioner Perez reaches out for it.

“You destroyed it to protect your mother.”

Estéban runs his fingers through his hair.

“I would say, rather, to protect myself.”

“What do you mean?”

“Let's just say there's nothing nice about me on this cassette. It made me angry.”

Estéban runs his fingers through his hair.

“But I can confirm, gentlemen . . . after listening to it . . . that my mother has no ambiguous feelings toward Dr. Puig. We cannot say that much about everybody.”

“What do you mean by that, young man?”

“What do I mean?”

Estéban runs his fingers through his hair.

“What do you think is going through the mind of a âyoung man' like myself, as you put it, when he sees his mother slowly wasting away . . . and the more she saw of this guy, the more distant she was with me . . . and the worst of it was that I was the one who had advised her to go and see him; I would have done better to have kept my mouth shut, but I'd heard so many good things about him . . . My mother was not at Vittorio Puig's place that night.”

“It's natural for you to think like that. A child can never believe in a mother's guilt. But you keep out of this, young man.”

“Stop calling me âyoung man'; I'll say it again, my mother was not at Vittorio Puig's place that night . . . it's true she often went there, too often, given the little good it did her, but she never went there in the evening, that would be the last straw . . . But I was there.”

“What did you say?”

“I killed Lisandra Puig.”

Eva Maria lets out a cry.

“I killed that woman to show the bastard what it means to lose the person who is dearest to you on earth . . . and after what I heard on the cassette, I'm not the least bit sorry. He let my mother say that she wished I had died instead of my sister, and he didn't even objectâI don't feel an ounce of remorse . . . that guy deserved to be taught a lesson; it was about time someone stopped him from causing any more harm.”

The lieutenant moves closer to Estéban.

“Señor Darienzo, we'll be taking you into custody.”

Eva Maria turns to the policemen.

“Don't believe him, please, you mustn't believe him, you can see he's just making things up, he's just saying that to protect meâmy son would never do such a thing, he would never kill anyone.”

Eva Maria turns to Estéban. She moves closer to him. Takes his hands.

“Go get your bandoneon, Estéban, play for them, then they'll see what a beautiful soul you have. My child has fingers of gold, and a heart of gold; he could never have killed that girl, he's just saying that to protect me, don't you see? He didn't even know her! And she didn't know him. She wouldn't have opened the door.”

Commissioner Perez shakes his head.

“I'm not at all sure about that.”

Estéban holds out his wrists to Lieutenant Sanchez.

“A woman always opens the door to a florist . . . It was just bad luck that my mother decided to defend that man . . . bad luck or her unconscious, because she didn't want me around anymore, so she led you to me without even realizing. This way she won't have to see me around anymore, since I constantly remind her of my dead sister.”

Eva Maria throws her arms around Estéban.

“Don't say that, Estéban, hush!”

Lieutenant Sanchez slips the handcuffs over Estéban's wrists. Eva Maria steps between Estéban and Commissioner Perez. She is shouting.

“Stop it! Vittorio was right. I stole the keys from him during our last session, I killed Lisandra, it was me, I did it; Vittorio has been right all along, about everything he told you, I'm fragile, I'm an alcoholic, I can't get over my daughter's death, I'm in love with him, I was jealousâthere, I confess, I confess to everything, what else do you want me to confess to? It was me, it was me, I killed that girl; tell me where I have to sign my confession, I'll sign it right away but don't take my son, please, please, leave me my son, leave my son out of this, take me, I'm ready, I'll come with you.”

Commissioner Perez and Lieutenant Sanchez stand on either side of Eva Maria.

“You'll sort it out at the station. In the meantime, we're taking both of you in. We have an innocent man to set free.”

Vittorio Puig has been set free.

Eva Maria Darienzo has not retracted her confession. Eva Maria Darienzo says she killed Lisandra Puig. An investigation into the murder has been ordered. Eva Maria Darienzo could get life imprisonment.

Estéban Darienzo has not retracted his confession. Estéban Darienzo says he killed Lisandra Puig. An investigation into the murder has been ordered. Estéban Darienzo could get life imprisonment.

The investigation lasts twenty-one weeks. The trial, nine days.

The jurors leave the courtroom.

The deliberation is lengthy. Complicated. The jurors are hampered by the double self-accusations. They are unsettled in their convictions. As a last resort, the jurors decide to go along with the findings of the psychiatric expert.

Eva Maria Darienzo could have killed Lisandra Puig. Estéban Darienzo could have killed Lisandra Puig. Either of them, for different motives. But in all likelihood, Eva Maria Darienzo is merely covering for her son's guilt. Estéban Darienzo is the true murderer.

The jurors file back into the courtroom.

Estéban Darienzo is sentenced to fifteen years' imprisonment for the murder of Lisandra Puig.

Eva Maria Darienzo is acquitted.

Eva Maria rushes over to her son. The police officers stop her. Eva Maria calls out to her son. She shouts to him that she loves him. Estéban turns his head toward his mother. Eva Maria is in tears. She shouts to him that she loves him. He smiles at her. Gently. Sadly. Estéban is handsome. Awkward. He runs his upper arm over his hair. With his wrists confined in handcuffs now, he can't run his hand through his hair, he can no longer respond to the tic he developed after Stella's death.

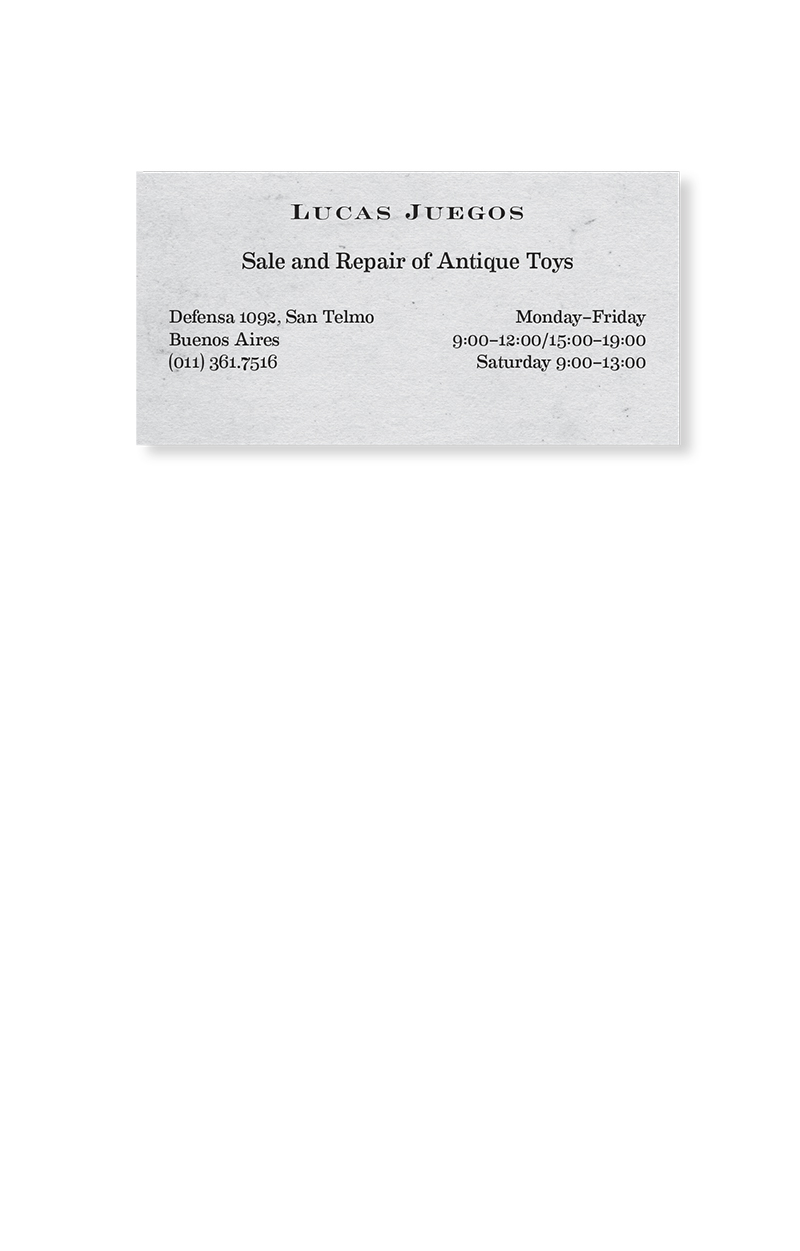

Vittorio is sitting in the gallery. He holds his head between his hands. Relieved. Satisfied. He pulls his gray jacket tight. The jacket he found hanging on the coatrack in the entrance to his apartment the day he got out of prison. It wasn't his jacket. It must have belonged to one of the many cops, journalists, and photographers who had set up their headquarters in his apartment while he was rotting in jail. Gang of primates. He had slipped on the jacket. It fit. Tough luck for whoever forgot it. Finders keepers, it was his now. For a split second the thought that it might belong to Lisandra's murderer crossed his mind, but he immediately shrugged it off. If the cops had found the jacket at the crime scene, they would surely have reserved a different fate for it than to hang it on the coatrack. It was time to stop seeing evil wherever he turned. His wife's murderer has just been sentenced. His heart sinks. Lisandra always used to buy his clothes: without her, he will end up wearing the same thing all the time. And this jacket? A sign from Lisandra. Signs, signs . . . He was beginning to think the way she used to. He hadn't checked the pockets in the jacket. His curiosity was always limited to human beings, never objects, let alone clothing. And if he'd been the curious sort, or simply a creature of habit, someone who was forever putting his hand in his pocket, what would have happened? In the right-hand pocket of the jacket he would have found a business card. “Lucas Juegos.” And then what would he have thought? Nothing, in all likelihood. What are you supposed to think about a business card from a toy store? So he would have thrown it out. Which is what he did, a few days later, but without realizing, along with other parking and restaurant receipts that he'd been stuffing in the jacket pockets since he'd started wearing it. Quite a few people had come to the hearing for his sake. His family, of course. And patients. Including Alicia. Including Felipe. Friends, too. Including Miguel, who

had returned from Paris specially for the trial. Everyone has been congratulating him, telling him how relieved they are.

Only Pepe, off in a corner, isn't applauding. He sees Vittorio's smile, sees him turn briefly to look at a woman in the back of the room.

The woman in the photo.

Eva Maria doesn't see her. Because she has eyes only for Estéban. And in any case Eva Maria wouldn't have recognized her. Because the woman is wearing dark glasses. Pepe hates those objects that the weather places between people. Vittorio gives her a scarcely perceptible nod. The woman smiles back. She is among the first to leave the courtroom. Discreetly. Only Pepe notices people's gazes. Their smiles. Vittorio's smile. But he won't denounce him. It wasn't the smile of a murderer who has just had someone else put away in his place. It was the smile of relief of an innocent man. The smile of a man in love.

People file out, using their designated doors. The door for the court and the jurors. The door for the public. The door for the condemned.

â¢Â â¢Â â¢Â

I am standing invisible in the room. Screaming. But no one can hear me. Screaming. So will no one ever know what really happened? Even though Lisandra planned everything so that the perpetrator would be punished. I am screaming. I am the daughter of Time, I am the mother of Justice and Virtue. Why has Life not given me the power to prevail? I am Truth. And I am screaming, from the memory.