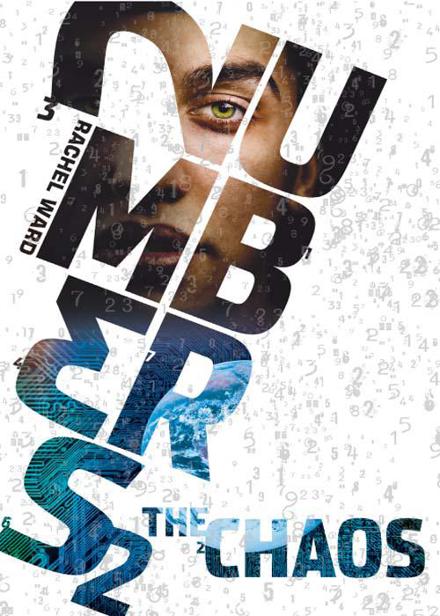

The Chaos

Authors: Rachel Ward

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Action & Adventure, #General, #Love & Romance, #Fantasy & Magic, #Paranormal, #David_James Mobilism.org

NUMBERS 2

THE CHAOS

RACHEL WARD

For Ozzy, my soulmate

Contents

Chapter 2: Sarah, September 2026

T

he knock on the door comes early in the morning, just as it’s getting light.

‘Open up! Open up! We’ve got an Evacuation Order on these flats. Moving out in five minutes. Five minutes, everybody!’

You can hear them going down the corridor, knocking on doors, repeating the same instructions over and over. I haven’t been asleep, but Nan nodded off in her chair, and now she jerks awake and curses.

‘Bloody hell, Adam. What time is it?’ Her face looks crumpled and old, too old to go with her purple hair.

‘Half-six, Nan. They’ve come.’

She looks at me, tired and wary.

‘This is it, then,’ she says. ‘Better find your things.’

I look back at her and I think,

I’m not going anywhere. Not with you.

We’ve been expecting this. We’ve been camped out in the flat for four days, watching the flood water rising in the

street below. They’d warned everyone that the sea wall was likely to go. It was built years ago before the sea level rose, and it wasn’t going to stand another storm with a spring tide to add to the swell.

We thought the water would come and then go, but it came and it stayed.

‘S’pose this is what Venice looked like before it was washed away,’ Nan said, gloomily. She flicked her cigarette butt out of the window and down into the water below. It bobbed slowly along the street towards where the prom had been. And she lit another fag.

The electricity was cut off that first night, then the water in the taps turned brown. People waded along the street outside shouting through loud hailers, warning us not to drink the water, saying they’d bring us food and water. They didn’t. Instead we made do with what we’d got, but with no toaster and no microwave, and the milk going off in the fridge, we were starting to get hungry after twelve hours. I knew things were bad when Nan took the cellophane off her last packet of fags.

‘Once these are gone we’re going to have to get out of here, son,’ she said.

‘I’m not going,’ I told her. This was my home. It was all I had left of Mum.

‘We can’t stay here, not like this.’

‘I’m not going.’ Statement of fact. ‘You can bugger off back to London if you like. You know you want to anyway.’ It was true. She’d never felt comfortable here. She’d come when Mum got ill, and stayed to look after me, but she was like a fish out of water. The sea air made her cough. The big bright sky made her screw up her eyes and she’d scuttle back inside like a cockroach as fast as she could.

‘Less of your language,’ she said, ‘and pack a bag.’

‘You can’t tell me what to do. You’re not my mum. I’m not packing,’ I said, and I didn’t.

Now we have five minutes to get ready. Nan stirs herself and starts putting more things into her bin bag. She disappears into her room and comes out with an armful of clothes and a polished wooden box tucked under her arm. She moves around the flat surprisingly fast. I feel a tide of panic rising inside me. I can’t leave here. I’m not ready. It’s not fair.

I get one of the chairs from the kitchen and lean it up against the door handle. But it’s not the right height to wedge the handle shut, so I just start grabbing whatever I can find and building a barricade. I push the sofa over, pile the kitchen chair on top, then the coffee table. I’m breathing hard, sweating between my shoulder blades.

‘Adam, what the hell are you doing?’

Nan’s tearing at my arm, trying to stop me. Her long yellow fingernails are digging in. I shrug her off.

‘Get off, Nan. I’m not going!’

‘Don’t be stupid. Get some of your things. You’ll want your things with you.’

I take no notice.

‘Adam, don’t be so fucking stupid!’ She’s clawing at me again, and then someone’s knocking on the door.

‘Open up!’

I freeze, and look at Nan. Her eyes show me her number: 2022054. She’s got another thirty years, near enough, but you’d never guess it. She looks like she could go any day.

‘Open up!’

‘Adam, please …’

‘No, Nan.’

‘Stand away from the door! Stand back!’

‘Adam—’

A sledgehammer smashes the lock. Then the door itself is shredded. In the corridor there’s two soldiers, one with the sledgehammer, the other with a gun. It’s pointing straight into the flat. It’s pointing at us. The soldiers quickly scan the rest of the flat.

‘All right, ma’am,’ says the gunman. ‘I’ll have to ask you to move that obstruction and leave the building.’

Nan nods.

‘Adam,’ she says, ‘move the sofa.’

I’m staring at the end of the rifle. I can’t take my eyes off it. In the next second, maybe less than that, it could all be over. This could be it. All I have to do is make a move towards him. If it’s my time, my day to go, that’ll be it.

What is my number? Is it today?

The barrel of the rifle is clean and smooth and straight. Will I see the bullet come out? Will there be smoke?

‘Fuck off,’ I say. ‘Take your fucking gun and fuck off.’

And then it all happens at once. The sledgehammer guy drops his hammer and shoves the sofa into the room like a rugby player in a scrum, the guy with the gun tilts it up to the ceiling and follows him in and Nan smacks me, right across my face.

‘Listen, you little bastard,’ she hisses at me, ‘I promised your mum I’d look after you, and I will. I’m your nan and you’ll do what I say. Now stop playing silly buggers. We’re leaving. And mind your fucking language, I told you about that.’

My face is stinging but I’m not ready to give in yet. This is my home. They can’t just take you away from your home, can they?

They can.

The soldiers grab an arm each and carry me out of the flat. I struggle, but they’re big and there’s two of them. It’s all so quick. Before I know it, I’m at the end of the corridor and down the fire escape and they’ve put me in an inflatable boat at the bottom of the steps. Nan gets in beside me, dumps the bulging bin bag by her feet and puts her arm round my shoulders, and we’re away, chugging slowly through the flooded streets.

‘It’s all right, Adam,’ she says, ‘it’s going to be all right.’

Some of the people on our boat are crying quietly. But most of their faces are blank. I’m still angry and humiliated. I can’t understand what just happened.

I haven’t got any of my stuff. I haven’t got my book. Another wave of panic sweeps over me. I’ll have to get out and go back. I can’t go without my book. Where did I leave it? When did I last have it? Then I feel the edge of something hard against my hip and my hand goes down to my pocket. Of course, it’s there. I haven’t put it anywhere – I’ve kept it with me, like I always do.

I relax, just a little bit. And then it hits me. We’re actually leaving. We’re going. I might never see the flat again.

There’s a big lump in my throat. I try to swallow it, but it won’t go. I can feel the tears welling up. The soldier steering the boat is watching me. I’m not going to cry, not in front of him or Nan or any of these people. I won’t give them the satisfaction. I dig my fingernails into the back of my hand. The tears are still there, threatening to spill out. I dig harder, so the pain breaks through everything else. I’m not going to cry. I’m not going to. I won’t.

At the transit centre, we stand in line to register. There’s one queue for people who have somewhere to go, and another one for people who haven’t. Nan and I aren’t

chipped, so we have to show our ID cards and Nan fills in forms for both of us requesting transport to London. They pin a piece of paper with a number onto our coats, like we’re about to run a marathon, then they herd us into a hall and tell us to wait.

People are giving out hot food and drinks. We queue up again. My mouth waters when we get nearer the front and I can see and smell the food. We’re four from the front when another soldier comes into the hall and starts barking out numbers, including ours. Our coach is ready. We have to leave now.

‘Nan …?’ I’m so hungry. I can’t go without getting something to eat, just something.

‘’Scuse me,’ I say, ‘can you let me through?’

There’s no reaction. Everyone’s pretending they haven’t heard.

I try again, as the soldier repeats the numbers. Nothing. I’m desperate. I dart forward and shove my hand through a gap between two people, and feel around blindly. My fingers find something – it feels like a piece of toast – and I pick it up. Someone grabs my wrist and holds on so tightly it hurts.