The Christmas Tree (2 page)

Read The Christmas Tree Online

Authors: Jill; Julie; Weber Salamon

Chapter One

Brush Creek

We'd flown over half of New Jersey, it felt like, and we were ready to call it a day. Not a single one of the trees I'd been told about had come even close to what we needed. I was barely paying attention by then, just enough to notice that this was one of the prettiest parts of the state. The landscape was lush and green, scarcely populated.

My head was nodding and I was just about to doze off. Then something made me sit up and look hard at the ground. For a second I couldn't tell if I was awake or asleep, I was so tired. But as my head cleared I knew I wasn't dreaming. There it was! No question about it.

This tree was a star. Everything about it said so: its rich color, the regal way it held itselfâeven where it stood, just apart from a whole group of evergreens, as if it was special.

“Can you go down a little?” I shouted over the noise of the chopper.

I held my breath. Usually closer inspection means disappointment. Half the branches are floppy, or the tree holds them too stiff.

Not this tree. It seemed to have that improbable combination I was looking forâthe size of King Kong, and the suppleness of Giselle.

My eyes wandered over the surrounding terrain, and settled on a large, elegant building.

“Do you know who owns this place?” I asked the pilot.

He glanced at a map. “That's what I thought,” he said.

“What is it?” I asked, impatiently.

“Nuns own it,” he said. “This is the Brush Creek convent.”

“A convent?” I said. “Isn't this a little plush?”

The pilot was a New Jersey boy and knew his way around.

“This is no ordinary convent,” he began.

I interrupted. “I can see that,” I said.

He was nicer than I was, ignored my wise-guy rudeness.

“Brush Creek was modeled after the grand estates of Europe,” he said, with the polish of a tour guide. “The man who built it wanted his children to see beauty wherever they looked and he had the means to do it. So the place has all kinds of orchards and pretty little valleys and woods. From what I've heard, sounds like he was an interesting guyâbesides making everything look nice, he started experimenting with conservation long before most people knew what the word meant. They say the house has so many windows that no matter where you go in it, you feel the pull of nature. He named it Brush Creek after the little stream that runs through the middle.”

He studied the map more closely, then pointed. “See, there it is. That squiggly line. That's the creek.”

I glanced at the map, then leaned forward to get a better look. The old man certainly accomplished what he set out to do. Brush Creek had beauty to spare. From the sky you could see its almost perfect design. I responded the way any professional gardener wouldâwith delight and not a small dose of envy.

“How did the nuns come to live here?” I asked.

The pilot shook his head. Funny, I'd been up with him on maybe a dozen trips and this was the first time we'd said more than a few words to one another.

“He planned to pass the estate on to his children,” he said. “But some things you can't plan for, I guess. His wife died a long time before he did and his kids had no real interest in keeping the place up. So when he heard about this group of nuns who devoted themselves to taking care of poor children all over the world he decided to give his home to them, as a place for them to take a rest from their work. Only one condition: They had to keep it exactly as it was.”

Neither of us said anything for a while, as if even this small exchange of local lore had been too intimate.

I broke the silence with a laugh.

“What's so funny?” the pilot asked.

“I was just thinking,” I said. “This should be a breeze. Who better to ask for a Christmas tree than nuns?”

I relaxed on the way back. It was still only Spring and I might just have gotten Christmas out of the way.

â â â

I drove out to the convent the next day.

I didn't mind getting out of the office. The building janitors were on strike and the place was in chaos. Now on top of everything else I had to do I was in charge of making sure everyone had trash bags. What a mess!

I've got a 22-acre operation at Rockefeller Center. We change the garden arrangement on the Promenade eleven or twelve times a year. I do the design, find the plants and am in charge of the planting, the primping and the pruning. Plus, we have 500 street trees to tend to and who knows how many indoor flowers and plants that have to be redone every two weeks.

And then there's the tree.

The guy who hired me used to take care of the tree. Now

he

was a sentimental guy. He loved doing it. Even when he got promoted he kept that part of the job. Once in a while he'd take me out with him. I thought he just wanted company. Little did I know he was grooming me to take over.

He knew I wasn't keen on it. But just before he retired he told me, “You're the gardener. You take care of the greenery around here. The tree is green. It's yours.”

“Thanks,” I muttered, making no attempt to hide my lack of enthusiasm.

“It'll be good for you,” he said laughing. “Soften you up a little.”

“Besides,” he added, “you're good at it.”

I've thought about giving the tree to someone elseâbut the truth is, much as I complain about it,

I am

good at it.

At least it gets me outdoors. I may be a gardener, but I spend most of my time parked in front of the computer or on the telephone. So spending a pleasant spring day in the country seemed just fine to meâespecially when I knew I had that tree in my sights. No dreaded dead ends in front of me this time.

It was a long drive into the prettiest part of New Jersey. The convent was set back quite a distance from the main road. The gravel drive leading to it was lined with dogwood trees in full bloom and I rolled down my window so I could bask in their scent.

Though I had seen the convent from the air, I wasn't prepared for the way it looked when I rounded the last bend. Propped up on top of a gentle slope, it had the imposing size of a castle, but the charm of a little girl's dollhouse. Mysterious tiny windows popped out of the steeply angled roof like secret peepholes, while the downstairs windows were huge, clearly designed to make the outdoors and indoors part of each other. The building seemed to go on forever; just just when it seemed my eyes had finally found the end of it, I spotted yet another wall angling off in another direction.

The nun who answered the door invited me in and then went to get Sister Frances, who ran the place. We had spoken on the phone.

As I stood in the foyer, I caught a glimpse of a large room full of beautiful paintings, comfortable furniture and luxurious carpets that looked like something out of the Arabian Nights.

I was taken aback by the swell surroundings.

“Do you like our home?” a friendly voice asked.

I looked up and saw a nun with a round pink face and amused, intelligent eyes watching me gawk. I laughed, a little embarrassed.

Sister Frances took me on a tour. Every room seemed flooded with light. “The Old Man made sure you could always look out, no matter where you sat,” she explained. So even chairs whose backs were to windows faced large mirrors angled so they offered a perfectly composed view of the outdoors. The main rooms were grand; the bedrooms were cozy and all of it was deliberate. We ended up in a large parlor, sitting in front of windows that opened onto the garden and the fields beyond.

“As you have probably gathered, this is no ordinary convent,” said Sister Frances. “Most of the nuns who come here don't live here. They work with children all over the world, usually in places that are far away, in every possible sense.”

Though Sister Frances moved and talked with the peppy enthusiasm of a natural organizer, I began to realize that her vigor was deceptive. Sister Frances had been around a long time.

We chatted a bit more about the convent, and about the small group of nuns who lived there all year round. I noticed that we weren't alone, though it was very quiet. There were nuns reading or talking in small groups in almost every room.

But it didn't take Sister Frances long to get down to business.

“So you're interested in one of our trees?” she said.

I told her I was and tried to describe its location as best I could.

She listened carefully, then smiled. “I thought so,” she said.

She began to get up from her chair, rather cautiously. I jumped to help her, but she waved me away, laughing.

“No, no. I've gotten around this earth for seventy-some years with God's help alone and I'm too old to change my ways now.”

Sister Frances made her way to the window and pointed. “Go down there and you'll see a path that will take you to your tree,” she said. “But the decision isn't mine. It's Sister Anthony's.”

I was heartened by her words. She did say “your tree,” didn't she?

“Where can I find Sister Anthony?” I asked her.

“Just go on down to the tree,” she said. “I suspect you'll find her.”

Chapter Two

Sister Anthony

The air was rich with the smell of spring. At first I walked with my brisk city steps, aimed toward my destination. But I slowed down to admire a fine orchard, and then, finding myself surrounded by so much beauty, began stopping every few yards.

It felt strange. Stopping. I'm always working a tight scheduleâthe big spring Flower Show at one end of the year, Christmas at the other and all of the ongoing plant exhibits in between.

Finally I arrived at a big stand of evergreens, just as Sister Frances said I would. My heart was beating fast, as I was about to go on a blind date. I couldn't believe my own foolishness.

I walked through the trees into a clearing. It took my eyes a second to adjust from the shadows to the light. I blinked, and there it was! The tree I'd seen from the sky, looking exactly as I hoped it would. It had the weight of majesty, the delicacy of grace.

“Hello there!”

I jumped a little. I'd been so mesmerized by the tree I hadn't even noticed the small figure in black standing at the far side of the clearing.

She walked over briskly and stuck out her hand.

“You must be the man from Rockefeller Center,” she said.

It took me a few seconds to respond. She had a surprisingly strong grip.

“Yes,” I said. “And you are ⦔

“I'm Sister Anthony,” she said.

Then she turned toward the tree.

“He's beautiful, isn't he?” she said.

“Wonderful,” I said.

“Well, young man,” she said, “come and talk to me.” She crossed over to the tree and sat down, with her habit spread around her like a tent that had collapsed.

There was something unnerving about this nun. She had the manner and the voice of a mature womanâshe was well into her fiftiesâbut the restless energy of a child. She moved faster than I did. Her face was small yet arresting, but it was her eyes that really caught me, so dark they were almost black, but very bright.

I sat down next to her feeling tongue-tied, like a kid. And, while I may have seemed young to Sister Anthony, I was no kid.

Since I didn't say anything, she began for me.

“So you want Tree,” she said.

“Tree?” I repeated blankly.

She laughed. “I'm sorry. It must sound strange to you, to hear an old thing like me talk that way. But I've known Tree since I was a little girlâand he was a sapling, for that matter. We grew up together.”

I was feeling like Dorothy must have felt when she landed in Oz. Weirder still, I liked it there, but I still had a job to do. I put on my doing-business voice. “So, I imagine you'd be thrilled to see your tree become the most famous tree in the world.”

Sister Anthony looked at me as though I was crazy.

“Why?” she asked.

I began to mumble something about making millions of children all over the world feel happy, but I already knew it was over. I didn't have my Christmas tree after all. It was May and in a minute it would be December and now, instead of cruising through the summer I'd be on the road looking for a tree that couldn't possibly be as good as this one.

She must have seen the misery on my face.

“Oh, I think it must be wonderful!” she said. “It's just not the thing for Tree. He has a lot of work to do here.”

Then she told me how the nuns would come to the clearing for special services, and have picnics under her tree in the summer, because his branches provided such lovely shade. She told me how she been teaching nature classes here in the clearing to children from town for so long that some of them had even brought their grandchildren to visit Tree.

All of this emerged in one long, cheery burst of words. Finally, she stopped and looked directly into my eyes.

“I haven't told you the entire truth,” she said softly. “Sister Frances told me why you were coming and said it was up to me. But there are many trees for you to choose from. I have only one Tree.”

My disappointment faded after I heard the intensity in her voice. There was a depth of feeling there I could only guess at.

I stretched my legs and started to pull myself to my feet.

“I guess I should go,” I said, as gently as I knew how.

“No, don't go,” said Sister Anthony. “I brought lunch.” She nodded at an old satchel lying on the ground. “When Sister Frances said you were a horticulturist I was hoping we might have a chance to talk. I'm considered the expert around here and it isn't easy being the one expected to have all the answers.”

“You're telling me,” I said, plopping right back on the ground.

She handed me a sandwich.

“So tell me,” she said. “What does it mean to be the chief gardener at Rockefeller Center?”

I liked talking to her. Her knowledge was impressive. It was nice to find someone who knew the difference between an azalea and a rhododendron. But inevitably, the talk turned to the Christmas tree and what a pain in the neck it was.

“It sounds like you

hate

Christmas!” she said.

I hesitated, then decided to tell the truth. It was that kind of day.

“I'm a horticulturist plain and simple. Christmas is a duty I didn't ask for.”

I knew I sounded like a curmudgeon, but I was tired of putting on a happy face about it, and she seemed willing to listen.

“You start dreading Christmas. It's the pressure. I live Christmas all year round. Before one Christmas comes, I'm working on the next. What's worse, you spend so much time trying to find this great tree and then people don't even understand what they're looking at. They've gotten so used to artificial trees or real trees sheared to âperfection' they think the individuality of a real tree is a kind of imperfection.”

She looked perplexed.

“Look up there, Sister,” I said. “See how your tree's branches go this way and that?”

She replied, a little defensive. “Why, that's what gives him character.”

I stopped and stared at her.

“What's wrong?” she asked.

I shook my head.

“Nothing. I was just surprised to hear you use that word.”

“Why?” she asked.

“Once,” I said, “a reporter was interviewing me about how we get the tree and she asked, âWhat makes one tree different from the other?' I tried to explain it to her. I talked about shading and triangles and density but I could see she wasn't satisfied. I was getting annoyed. I didn't have time for this. How do you explain a feeling you have for something to somebody who hasn't experienced it?”

Then Sister Anthony said gently, “Well, what did you tell her?”

“Character,” I said. “I told her it's character. Like if you met Jackie Onassis or Katharine Hepburn. Some have more beauty but none have their presence. They hold the room.”

We sat in silence for a while, eating our sandwiches.

Sister Anthony spoke, with a teasing note in her voice. “Well, perhaps you don't hate Christmas so much after all.”

I was a little embarrassed at having let my guard down. I generally like to play it cool.

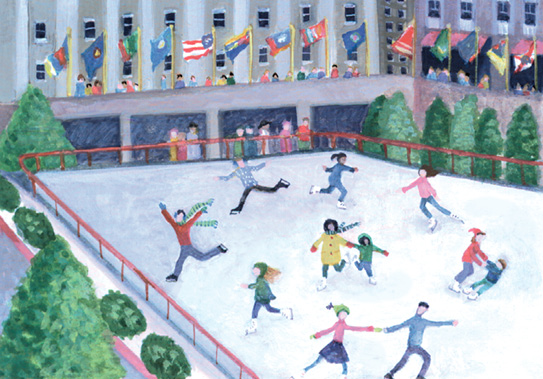

I shrugged. “For me it's like theater. We build the set, light the tree and pull the curtain! The show begins.”

She raised her eyebrows.

“All right,” I said. “It's pretty poetic if you're a visitor. Especially when it snows. The ice skaters out on the rink below the tree, the bushes, they all sparkle, like they're trying to outdo the tree. You know what I mean?”

She shook her head. “Not really.”

I was incredulous.

“Haven't you ever seen the tree at Rockefeller Center? On television, at least?”

She shook her head again, smiling. “I don't venture far from Brush Creek and we don't have a television. We try to keep things quiet for our visiting nuns. They need a rest from the troubles they see in the outside world.”

It was one of those times when you realize there are always limits on the kinship you may feel for someone. Sister Anthony might know a lot about nature, but what did she know of the real world? I felt like a jerk for having opened myself up to her, for thinking that she would understand.

She looked upset, as though she, too, sensed that the moment between us had been lost. Hoping to make a polite exit, I launched into my standardized riff on the tree.

“I see the tree as the crown jewel of Rockefeller Center,” I was saying in a monotone, when Sister Anthony seemed to drift off to some other place.

“The city is our jewel,” she murmured.

“Excuse me?” I said.

She repeated herself. “Anna, the city is our jewel.”

I shook my head. “I don't understand.”

When she didn't reply I reached over and tapped her on the shoulder.

Now it was her turn to look surprised. She shook her head and started to get up. “You'll have to forgive me,” she said. “Something you said took me back to another time.”

“Who was Anna?” I asked her.

She settled back on the grass. “I don't think she would be of much interest to you.”

“Too late for that,” I said. “Tell me.”

Suddenly the sense of camaraderie I'd felt before returned, as quickly as it had vanished. Sister Anthony seemed as she had been, vigorous and full of humor.

“It's no great mystery,” she said. “I was Anna, many many years ago.”

She looked mischievous. “It may surprise you, but we nuns don't arrive on this earth wearing habits, you know. I was a little girl once. And I was born in New York City.”

“Tell me more,” I said.

“So you'd like to hear a story, would you? All right,” she said, “I'll tell you how a girl named Anna from New York came to Brush Creek.”

A change came over her then, and I realized that she was either a born storyteller or a practiced one. It came as no surprise to hear her begin with “once upon a time.”