The Christmas Tree (8 page)

Read The Christmas Tree Online

Authors: Jill; Julie; Weber Salamon

Chapter Eight

The Journey

I made sure the powers that be at Rockefeller Center sent a special invitation to the Sisters of Brush Creek. It began,

We would be honored to have you present at the annual Christmas Tree Lighting Ceremony

, and was printed on a thick, cream-colored card, lettered in red and green type. Pretty classy.

Sister Frances called me a few days after she received it, full of excitement and thanks. She told me she'd set the card on the little table in the vestibule and put out a sign-up sheet, to find out how many of the nuns wanted to go, and that it filled up with names in a day. Not only that, word had spread about the tree and the trip to the cityâand many people wanted to come along, people who remembered the happy times they had spent under Sister Anthony's tree when they were young.

When Sister Frances added up the names of everyone who wanted to go, she realized there were far too many people for the convent van to carry. That didn't stop her, though. The convent had funds for special occasions, and she thought this was as good an occasion as she could imagine to spend some of that money. So she chartered a caravan of buses. She wanted to find out if I could arrange parking for them. No problem, I told her.

Then, two weeks later, she called again.

“I'm sorry to bother you,” she said, “but I have a problem. I've been so busy running around preparing for the trip I didn't really notice how quiet Sister Anthony has been lately. Then, yesterday, I was looking over the list to see who had signed up and I realized someone was missing.”

I interrupted. “She isn't coming?”

“Don't rush me, young man,” said Sister Frances.

Obviously she was going to tell the story her way.

“The minute I realized she hadn't signed up I found her in the library and, I'm ashamed to say, spoke rather sharply to her.”

I couldn't help smiling, imagining the showdown between these two.

“She asked me if something was wrong and I said, âYes, indeed there is. Why aren't you coming to Rockefeller Center with us?'

“I already knew the answer, of course. I must say, my heart went out to her, but I told her, âThere's a time to say good-bye.'

“You know what she said to me? âI've already said good-bye.'

“At that moment she seemed like that sad little girl I'd seen almost sixty years ago, looking so lost and alone.

“âAre you sure?' I asked her. Well, I could just see from the look on her face that I wasn't going to change her mind.”

There was silence.

“Sister Frances?” I said.

“Yes,” she said, sounding somewhat startled. “Oh, yes. That's why I'm calling. I need you to come out to Brush Creek the day of the tree lighting and bring Sister Anthony to Rockefeller Center yourself. You're the only one who can do it. I'm counting on you.”

And then she hung up.

At first I wanted to call her back and tell her it was impossible. How could I spend the biggest day of my year driving all the way out to the middle of New Jersey and back? But my next thought was, how could I not?

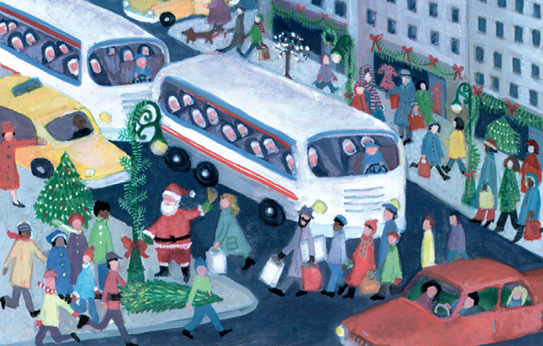

When I arrived at Brush Creek the buses were already there. It was a long way into the city and the weather was poor for traveling. The temperature hovered around freezing, and the light snow that had begun to fall was wet and sloppy.

Despite the gloom outside, inside the convent felt festive. The main room was full of nuns, the townspeople who were going along and a huge number of children, some of whom I recognized as Sister Anthony's students.

Sister Frances was in her element, lining people up and telling them which bus to get on. You could see she was happiest when she held a clipboard in her hand.

When she saw me she didn't even say hello. She just nodded toward the back. “She's out in the greenhouse,” she said. “She doesn't know you're coming.”

“That's just great,” I said to myself, kicking myself for coming on this fool's errand. What made meâor Sister Frances, for that matterâthink I could change Sister Anthony's mind? And why should we try? Was it our place to decide how Sister Anthony should deal with the end of the most meaningful friendship she'd ever had? We couldn't even begin to understand the connection between her and Tree, and what it meant to have it broken.

I wanted to turn around and drive right back to New York, where I belonged. I didn't have it in me to be anyone's spiritual advisorâleast of all a nun's.

While all of this was going through my mind Sister Frances was still tending to her list. When she saw I hadn't budged, she waved me away. “Go on,” she said impatiently. “There isn't much time.”

There was no answer when I knocked on the door of the greenhouse so I just went right on in. I could hear Sister Anthony in the back, bustling about, humming to herself. As I started in her direction I knocked over a watering can.

Sister Anthony looked up with a start.

“What are you doing here?” she greeted me. “Isn't this your big day?”

“Nah,” I said. “I'm already onto the next thing. I'm in the middle of planning the Spring Flower Show. As far as the tree goes, I'm more or less finished. There are a lot of other people who take over now.”

I wasn't exactly lying, then again I wasn't exactly telling the truth either. It was true that the tree was in the hands of the electricians and the public relations people by now. But this was the first time I had ever been somewhere else on the big day: I was usually there prowling around, making sure everything was running smoothly.

She just looked at me, waiting.

“So, I heard you weren't coming,” I said.

“That's right.”

That was it. She wasn't going to make this easy. I took a deep breath.

“Look,” I said, “I know it may be none of my business but I really think you should go see Tree.”

She looked surprised. “I don't think I've ever heard you call him Tree before,” she said.

I knew I had to keep going before I lost my nerve. Then it just all came out. “Sister Anthony, I don't know how to say this, exactly. I've spent most of my adult life trying to create beauty. I mean, that's my jobâto create an impression, to wow people. Plants and trees are my tools, I use them like my computer and my Rolodex. At least that's what I've always told myself.”

I couldn't think of what to say next. I felt like such a jerk. What was I doing?

Sister Anthony's eyes were sympathetic. And as she waited patiently for me to get my thoughts together, it occurred to me that she was helping me out once again, though I was the one who was supposed to be helping her.

“I guess what I'm trying to say is, well, that it's all a lie.”

She looked puzzled. “What do you mean?”

“I mean it's not just a job, they're not just tools and I really do love what I doâand you've helped me see that. You and Tree. So please come with me. I'd like you to see where Tree has gone. It's important.”

I stopped. I didn't know what else I could say.

Sister Anthony was silent.

“Please,” I said.

â â â

We didn't talk much on the drive into the city. I could see Sister Anthony taking in all of the ugliness as the beautiful countryside of rural New Jersey gave way to shopping malls and giant oil tanks and chimneys billowing smoke. It was all new since she had made her trip to Brush Creek so many years before.

Finally, we could see the city in the distance, but just barely. The air was thick with a frozen haze.

“On clear days the skyline just seems to sparkle,” I said trying my best to sound cheerful.

Sister Anthony nodded politely.

“Is it familiar at all?” I asked her.

She shook her head. “Not at all.”

I was thinking we should just turn around and go back. This was a terrible mistake. What would she make of all the hoopla which was part of the tree-lighting ceremony, with its big-name performers and politicians and TV cameras. I was afraid that if the crowds didn't overwhelm her, the entertainment would.

The traffic was murderous. We crawled across town. She kept shaking her head. “I don't remember anything,” she said. “Nothing.”

Then in a sad voice, she said, “This is what I feared most of all, you know.”

“What's that?” I asked.

“I've always had a good feeling about New York, something I've never been able to put my finger on. Just a general kind of warmth,” she said. “But thisâthis isn't it!”

I looked out of the window and tried to imagine how it looked to her: It was all grayâgray people huddled over as they made their way across gray streets that were bordered by gray buildings. The only thing that wasn't gray was the noiseâbig red blasts of horns blowing and walkers and drivers cursing at one another and of course the ever-present sirens.

I wished that we could have driven down Fifth Avenue. At least then she'd have a chance to see the Christmas decorations and the angels lighting the path to the tree. But I knew the traffic would be a nightmare so we stopped near Sixth Avenue and made our way across Fiftieth Street, pushing through the mob that surrounded the area that we'd roped off for the nuns. Sister Anthony didn't complain but she looked miserableâtiny and frail in the crush and the cold. For the first time since I'd met her, she seemed old.

“It'll be great when we get there, you'll see,” I said, elbowing people aside to make a path for her.

We finally made it. I got a glimpse of Sister Frances and her group but before I had a chance to look up, to see if the tree was actually there, one of my guys grabbed me by the arm.

“We've been looking all over for you,” he yelled and took me with him.

By the time I'd taken care of whatever it was, I couldn't make my way back to Sister Anthony. I caught her eye from a distance and waved at her helplessly as the ceremony began. She smiled and waved back, a bit too heartily to be convincing.

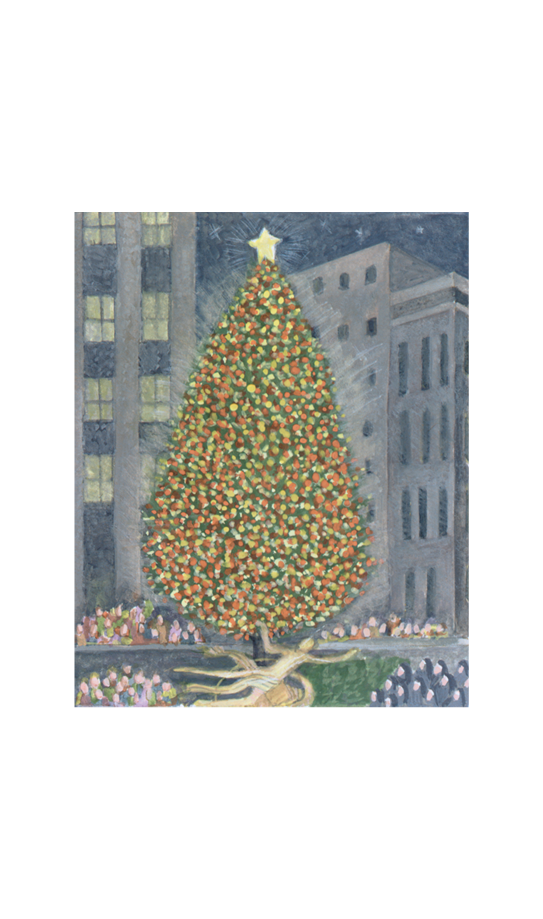

It all happened so quickly. There were the speeches and the singing and the tree was lit.

I didn't pay attention to any of it. I kept my eyes on Sister Anthony, trying to make out what she was thinking. At first she looked troubled.

“She shouldn't have come,” I muttered to myself.

Then something happened. Her face lit up and she looked years younger, almost like a child. She was smiling as she lifted her hand toward the tree and her lips moved. I'm pretty sure she said, “Good-bye my friend.”

When it was over I tried to reach her. But the crowd closed in on me and by the time I made my way over to where the nuns had stood they were gone.

Chapter Nine

The Christmas Tree

Over the next few weeks I kept meaning to get out to Brush Creek for a visit. But things caught up with me, the way they always do. As usual I was busy growling about next year's Christmas tree and what a pain in the neck the whole thing was.

Then I got her letter. It arrived at the office one day when I was in a particularly bad mood. When my secretary buzzed me to let me know the helicopter pilot was waiting for me, I barked at her. “Let him wait!” I said.

I closed the door and began to read.

â â â

I was right. The crowds and the entertainment had all seemed overwhelming. She was wishing she hadn't come. She was frightened. Worst of all, she didn't recognize her tree in that place, surrounded by huge buildings instead of the sky, its branches weighed down with a brightness that all seemed false.

Then the lights came on and way up at the top, the star.

Here. I'll let her tell you the rest.

I was overcome by the memory of a star from long ago, she wrote. Suddenly I remembered that I had been there before, at that very place, with my father and that he had said the strangest thing. “The city is our jewelâbeautiful yet hard.”

I remember at the time I was a little frightened by his voice. There was a depth of sorrow there that I had never heard before. Later I realized he knew what I didn't, that he was dying.

He must have sensed that I was scared, because when he spoke again I heard the gentle tone I was used to.

“See that star, Anna, there at the very top?” he said. “It's there to remind us of the beauty, even when all we feel is the hardness.”

Standing there with Sister Frances and the others, I finally understood what my father was trying to tell me, and how much it must have hurt him, knowing that he wouldn't be able to teach me all the things he wanted to. I felt so proud of him, remembering that moment, and so lucky to have it come back to me. My fears just disappeared.

I looked around and saw the happiness on the faces of the people who were dear to me, and the strangers, too. I looked for you, but couldn't find you in the crowd. But the crowd no longer scared me because I could see that the people in it were doing just what my father had said to do. They were looking for the beauty.

And they found it. My Tree gave it to them.

He was beautiful, wasn't he? And I was able to see him, underneath all his finery. It was my Tree after all.

Everyone here at Brush Creek is still talking about how exciting it all was. Otherwise, everything is pretty much back to normal. I've been reading about a new variety of tomato I want to try this summer, and puttering around the greenhouse. I'll be glad when it warms up and I can get out in the garden again.

You must come and visit us soon. I've told this year's group of children all about the Christmas tree and about the clever man who chooses it. They think that must be a wonderful job to have. Just come out to the clearing any day in the early afternoon. You'll find me there, next to the little Norway spruce the children and I planted this week.

You were right to make me go. You're a good friend, and for that I thank you.

I had to sit there for quite some time before I could move. My head and my heart were full. Finally, I put the letter in my desk and walked out of my office, feeling strangely light.

I saw my secretary staring at me.

“Well, you look a little happier,” she said. “What did you do? Take a nap?”

“Why shouldn't I look happy,” I said. “I'm going out to find a Christmas tree.”