The Cold War: A MILITARY History (16 page)

Table 7.2

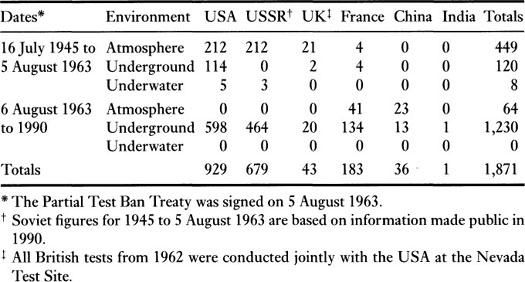

Nuclear Weapons Tests

4

One particular shortcoming of the testing programme was that, because of the fallout problem, only a very small number of the atmospheric tests carried out (

see Table 7.2

) were properly monitored groundbursts, the remainder being airbursts and high-altitude bursts or underground tests. This meant that assessments of the effects of groundbursts had to be based upon mathematical models, which might or might not have been accurate.

Another significant unknown was the effect of multiple explosions. At Hiroshima and Nagasaki and in all known subsequent tests, only one nuclear weapon was ever detonated at a time. Thus the possible effect of tens or even hundreds of more or less simultaneous nuclear explosions over a relatively small geographical area such as Germany or the western USSR was simply not known, and there could have been cumulative effects which were unforeseeable.

Another unknown was the behaviour pattern of people. In general terms, during the Second World War the mass of people contradicted what was thought to be the ‘lesson of Guernica’

fn11

and stayed put in their cities. Indeed,

instead

of rioting and bringing massive pressure to bear on governments to surrender, as had also been predicted, not only did they remain passive, but in many instances the attacks actually increased their determination to resist. Attacks by V-1 and A-4 (V-2) missiles on cities such as London and Antwerp gave rise to slightly greater degrees of panic than did manned bombers, but not on the scale the Germans had expected. The threat from nuclear weapons was, however, different by many orders of magnitude, and included not only immediate damage on an almost unimaginable scale but also the certainty of long-term suffering for those who survived. How people might have responded to that threat was simply impossible to predict.

It must therefore be borne in mind throughout this book that the forecasts of the effects of individual nuclear weapons, especially groundbursts, and the predictions of the outcomes of nuclear wars were essentially ‘best guesses’. They were also very sensitive to the assumptions on which they were based, and it was by no means unknown for officials and academics (in both East and West) to ‘fine-tune’ their assumptions in order to produce outcomes favourable to the case they were trying to make.

fn1

A list of nuclear-weapons ‘firsts’ is given in

Appendix 6

.

fn2

Trinitrotoluene (TNT) is the ‘standard’ chemical high explosive.

fn3

For practical purposes, this means that the bottom edge of the fireball is 20 m above ground level.

fn4

Ambient pressure is approximately 1 kgf/cm

2

.

fn5

Ground zero (GZ) is the point on the earth’s surface vertically above or below the centre of a nuclear explosion. At sea, the equivalent is surface zero (SZ).

fn6

Two units are used to measure radiation: the

roentgen

measures exposure and the

rad

measures absorption. For the purposes of this book, the two are essentially synonymous (i.e. 1 roentgen = 1 rad) and the rad will be used. The absorbed radiation can be expressed either as a dose rate (rads per hour) or as an accumulated figure (total rads over a specified time). To confuse matters further, NATO recently redesignated the

rad

as the

Grey

, but, since it was the term commonly used throughout the Cold War, the term rad will be used here.

fn7

The main NATO communications system in Europe, designated ACE HIGH, used tropospheric scatter, whose value in the aftermath of a series of nuclear explosions would have been questionable, to say the least.

fn8

In a well-documented event, the street lighting on the Hawaiian island of Oahu suffered thirty separate and serious failures due to the EMP from a test which took place at Johnson Island, some 1,300 km distant.

3

fn9

In the NATO Central European Command, for example, all military units were required to make and to practise plans to deploy from their peacetime camp to a ‘survival location’ at some distance from their barracks. Such emergency deployments were to be implemented on receipt of a codeword (originally ‘Quicktrain’, later ‘Active Edge’).

fn10

Such facilities included ‘crisis management centres’ (operations rooms), ‘hardened aircraft shelters’ (HAS), ‘hardened equipment shelters’ (HES), pilot briefing facilities (PBF), etc.

fn11

During the Spanish Civil War (1936–9), the small town of Guernica was heavily bombed by German aircraft operating in support of General Francisco Franco. This was the first example in Europe of ‘modern’ bombing, and led to many false conclusions about the effect of such bombing on civil populations.

8

Nuclear War-Fighting Systems

THE SECOND WORLD WAR LEGACY

AMONG THE MANY

military legacies of the Second World War, two of the most significant were land- and sea-based ballistic missiles,

fn1

which quickly enabled the two superpowers to threaten each other directly. The German A-4 (V-2)

fn2

rocket entered service in 1944 and carried out attacks on the UK, Belgium and the Netherlands in a programme unique in the annals of warfare, the concept, delivery system, propulsion, guidance and method of deployment all being totally new.

Because it was developed by the army as a form of very-long-range artillery, the A-4 was highly mobile, using a simple transporter–erector, while its size was the maximum that could be transported through a standard European railway tunnel. The missile had a range of approximately 320 km, and the warhead contained 910 kg of high explosive (Amatol). Some 4,320 A-4s were launched in anger, the principal targets being London and, later, Antwerp. The A-4 caused the Allies severe problems in the last months of the war, because there was no known defence against it, other than overrunning the launching sites on the ground.

The German missile designers’ sights were aimed at even more distant targets, and presaged the intercontinental-missile era with two plans for

ballistic-missile

attacks on the continental USA.

fn3

The first of these envisaged mounting an A-4 missile in a submerged container/launcher which would be towed across the Atlantic behind a submarine – the embryo of the concept of submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), which were to appear in the late 1950s. The second was for a two-stage missile with a 5,000 km range; this would have been launched against New York from sites in western France – the precursor of the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). Both projects were technically feasible, but, fortunately for the Allies, the Germans ran out of time before either could be implemented. As a result of the success of the A-4, however, the Americans, Russians and British captured as many A-4s as they could, and took as many sample missiles, designs and designers as they could lay their hands on back home to develop new versions of these ‘terror weapons’.

Such missiles, coupled with the most significant weapon of all, the atomic bomb, also brought into the realms of possibility the destruction of the civilized world in what US president Jimmy Carter once described as ‘one long, cold, final afternoon’. The atomic bomb gave military planners new destructive power, far in excess of anything that had gone before, with one bomber or missile able to carry a warhead more powerful than thousands of its predecessors. Not surprisingly, these new weapons and new delivery means required novel strategic concepts for their use, one of the most important – and contradictory – elements of which was that they would truly fulfil their function only if they never had to be used.

THE BACKGROUND TO STRATEGY

Nuclear strategy and nuclear-weapon targeting in the Cold War were very complicated businesses, not least because all those involved were venturing into the unknown. The USA declared itself wedded to the concept of deterrence, whose fundamental proposition was that a rational opponent would not attack if the risks of retaliation outweighed the predicted gains of the attack. Caspar Weinberger, secretary of state for defense under President Reagan, stated that, to be effective, deterrence had to meet four tests:

• Survivability: our [i.e. US] forces must be able to survive a pre-emptive attack with sufficient strength to threaten losses that outweigh gains;

• Credibility: our threatened response to an attack must be credible; that is,

of

a form that the potential aggressor believes we can and would carry it out;

• Clarity: the action to be deterred must be sufficiently clear to our adversaries that the potential aggressor knows what is prohibited; and

• Safety: the risk of failure through accident, unauthorized use, or miscalculation must be minimized.

1

In other words, an aggressor who was considering a first strike would be deterred from carrying out an attack on the enemy’s population centres if he considered that the enemy would retain both the capability and the will to attack the aggressor’s population in turn.

At least in public, the Soviet Union was very dismissive of the doctrine of deterrence, but such a concept seems to have been at the heart of Marshal V. D. Sokolovskiy’s statement in 1975 (in what may be assumed to be a close reflection of the Kremlin’s views) that:

Nuclear rocket attacks by strategic weapons will have decisive primary significance on the outcome of a modern war. Mass nuclear attacks on the strategic nuclear weapons of the enemy, on his economy and government control system, with simultaneous defeat of the armed forces in theatres of military operations, will make it possible to attain the political aims of a war in a considerably shorter period of time than in past wars.

2

Sokolovskiy then went on to say that:

The basic aim of this type of military operation is to undermine the military power of the enemy by eliminating the nuclear means of fighting and formations of armed forces, and eliminating the military–economic potential by destroying the economic foundations for war, and by disrupting governmental and military control. The basic means for attaining these ends are the Strategic Rocket troops equipped with ICBMs and IRBMs with powerful thermonuclear and atomic warheads, and also long-range aviation and rocket-carrying submarines armed with rockets with nuclear warheads, hydrogen and atomic bombs. These ends can be achieved by attacks on selected objectives by nuclear rocket and nuclear aviation strikes. The most powerful attack may be the first massed nuclear rocket strike with which our Armed Forces

will retaliate against the actions of the imperialist aggressors who unleash a nuclear war

[my italics]. In making nuclear rocket and nuclear aviation strikes, military bases (air, missile and naval), industrial objects, primarily atomic, aircraft, missile, power and machine-construction plants, communications centres, ports, control points, etc. can be destroyed.

3

In other words, the Soviet Union would have responded to a Western first strike with a massive counter-attack, directed against both military and military–industrial targets.

There were three important elements in the strategies of both sides. The first was that each side needed to have an accurate knowledge and understanding of the opponent’s value system, especially when judging what

would

be considered ‘unacceptable’ and ‘credible’. Second, peacetime discussions and war gaming were inevitably conducted in ‘ivory-tower’ conditions. The third factor in the strategic area was whether or not it was feasible to use what were termed ‘tactical nuclear weapons’ on the battlefield or at sea without escalating immediately to strategic nuclear warfare.

One of the fundamental requirements of deterrence, at least as discussed within the United States, was that commanders and planners needed to be certain about what the rational planner on the other side would find to be totally unacceptable. The problem was, of course, that perceptions of unacceptability can differ widely. The Russian people have been notable during many centuries for their stoic resistance to suffering; during the Second World War, for example, the western part of the USSR suffered dreadfully, with at least 20 million deaths. Nevertheless, the Soviet Union recovered remarkably quickly after the war. Further, in a state such as the USSR, where one group dominated a number of disparate groups, it seems possible that a nuclear strike in the Ukraine or Kazakhstan might not have been considered ‘unacceptable’ to an ethnic Russian in a command bunker in Moscow, while a nuclear attack on Moscow might have had little relevance in Siberia.

The countries of western Europe also had experienced suffering. Germany had incurred tremendous losses among its young male population, and the state had been almost totally destroyed twice in the space of thirty years, but the recoveries had been both rapid and complete. France had been occupied and had its territory fought over twice, while the British had been bombed but not occupied. British, French and German post-war planners might therefore have had some, albeit differing, perceptions of the Russian wartime suffering and what Soviet leaders might have deemed to be ‘unacceptable damage’. A US planner, brought up in a country which had never suffered a direct major attack, would have had a different perception still. On the other hand, despite the openness of Western society, the Soviets may not have had sufficient knowledge and understanding of Western countries to be able to judge correctly what the United States or western Europeans would consider unacceptable losses.