The Cold War: A MILITARY History (59 page)

Contingency Plans

The military staff tried to picture every possible contingency which might arise, and then prepared a plan to deal with it.

fn12

In 1962, for example,

the

military plans, known as ‘BerCons’ (Berlin contingency plans), included:

2

• BerCon Alpha 1 – large-scale fighter escorts for transport aircraft using the Berlin air corridors;

• BerCon Alpha 2– conventional battle for air superiority over Berlin;

• BerCon Bravo – five low-yield, airburst nuclear weapons against selected targets, to demonstrate Western resolve to resort to more powerful nuclear weapons if necessary;

• BerCon Charlie 1 – an attack by a reinforced division along the Helmstedt–Berlin autobahn;

• BerCon Charlie 2 – an attack by two divisions (i.e. a weak corps) in the Kassel area;

• BerCon Charlie 3 – an attack by three divisions (i.e. a normal corps) from Helmstedt along the axis of the Mittellandkanal as far as the river Elbe;

• BerCon Charlie 4 – an attack by three divisions towards Berlin, launched from the Thüringerwald area in the US zone.

There were also plans for a tripartite battalion group, which comprised a British infantry battalion, a US tank company, a French armoured-car platoon, a US engineer platoon (including an armoured bridgelayer), and a leading platoon made up of equal numbers of infantrymen from the three nations. Such a force was designated Trade Wind if mounted from West Germany or Lucky Strike if mounted from West Berlin.

The contingency plans developed by Live Oak from 1959 onwards included possibilities physically far removed from Berlin and even from Germany. There were, for example, a number of naval plans (known as MarCons – i.e. maritime contingency plans) consisting of a series of naval measures, varying from distant blockades of the type that had been so successful off Cuba to close-in blockades off Soviet ports such as Vladivostok.

Naval operations in support of Berlin were occasionally very positive. In May 1959 there was a feeling of crisis over Berlin. There had been a number of incidents on the autobahn and more trouble over the 3,050 m aircraft ceiling, and a Four Power foreign ministers’ conference was held in Geneva, opening on 11 May. One of the measures taken by the Western Allies was for the US Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean to ensure that at least one carrier task group was at sea throughout May, with each carrier maintaining at least six aircraft at immediate-launch status. Again in 1961, during the crisis caused by the erection of the Berlin Wall, the Sixth Fleet was placed on the alert, and on this occasion was reinforced by extra long-range ASW aircraft, while a further ASW carrier group was deployed to the Norwegian Sea.

3

All such plans included arrangements for informing the Soviets that these actions were directly related to Berlin, which was usually achieved

through

the Washington Ambassadors Group, consisting of the US secretary of state and the French and UK ambassadors (with the informal presence of the West German ambassador).

Air Reconnaissances

The Berlin Airlift demonstrated that the air corridors were essential to the survival of the Western garrisons, and a number of contingency plans were devoted to ensuring that such access continued. One plan, devised by Live Oak in the early 1960s, involved flying a civil airliner of the type normally used on the Berlin run down one of the air corridors if there was any threat to close it. It was, of course, appreciated that this was not a reasonable mission for a civil aircrew, so, in the British case, the Royal Air Force negotiated a contract with state-owned British European Airways (BEA), which involved six military crews being trained to fly the then current Viscount turboprop airliner. The plan was that, during a crisis, one of these aircraft would be taken over by the British air-force aircrew at Hanover Airport and flown without passengers to Berlin (Tempelhof) and back.

This contingency plan was actually put into operation for the first time on 16 February 1962, at the request of General Lauris Norstad (CINCEUR), although all did not go as smoothly as had been intended.

4

First, despite the planning and training, when the time came BEA officials refused to hand over one of their aircraft to the air force. This was in part because they did not believe the threat to be sufficiently serious, but also because they were concerned at the commercial consequences of one of their aircraft being shot down or otherwise forced to land by the Soviets, who would then discover that a civil airliner was being flown by a military crew. The matter was so complicated and feelings ran so high that it had to be resolved by a meeting between the company chairman, Lord Douglas, and the secretary of state for air, where Douglas, albeit with considerable reluctance, eventually agreed to make the aircraft available. It was duly taken over, and the flight plan for the

northern

corridor was cleared with the Soviet representative at the Berlin Air Safety Centre, whereupon the crew flew the aircraft down the

central

corridor. Not surprisingly, such an error caused considerable embarrassment, although, despite the tensions at the time, the Soviets failed to take any advantage. There were, however, serious repercussions in London, where it was eventually established that there had been a misunderstanding between the relevant authorities in Berlin and Hanover. The US forces developed a similar arrangement with Pan American Airlines, as did the French forces with Air France.

Land Reconnaissances

In any crisis on land, the initial aim of the Western Allies was to establish the seriousness of the Soviet threat. This was achieved by using a tripartite force

known

as a ‘probe’. The codewords changed over the years, but in the 1960s this operation was known as Operation Free Style if the probe force was mounted from the West German end of the autobahn and as Back Stroke if it was mounted from the Berlin end. Such probes were always preceded by a very precise warning to the Soviets, and there were three levels:

• If it was planned to accept any Soviet physical obstruction of the autobahn and to turn back without further discussion, the probe force would consist of fifty-six men in fifteen vehicles.

• If it was planned to accept any physical obstruction placed by the Soviets but only to turn back on being forced to do so (i.e. following protests and a confrontation), the probe force would consist of seventy-seven men in eighteen ‘soft’ vehicles (i.e. trucks) and two armoured personnel carriers.

• If it was planned to take positive action to remove any physical obstructions, but only to use force in self-defence, then the force would consist of 120 men, mounted in twenty-two ‘soft’ vehicles, two armoured cars and two armoured personnel carriers.

INCIDENTS

In total there were many hundreds of incidents involving the Western garrisons during the years they were in Berlin, ranging from the trivial to the extremely serious, with causes varying from incompetence, overenthusiasm or accident to sophisticated planning and co-ordination. In November 1950 tension in Berlin led to the Western Allies reinforcing their garrisons, which included reinforcements from the US 6th Infantry Regiment, together with a British tank squadron equipped with thirty Comet tanks. Then in May 1951 land travel between East and West Berlin was cut, and telephone systems were severed.

The period 1950–51 also included the ‘barge war’ between the British (who controlled three important canal locks in Berlin) and the Soviets. This started with the Soviets interfering with barge traffic between the Western occupied zones and West Berlin; the British responded firmly to this at their locks, where they stopped all East German traffic. This was resolved by an agreement signed on 4 May 1951, although the Soviets and the GDR later built a new stretch of canal, which removed the need for them to use the British-controlled locks.

May 1952 saw intermittent interference with Western military traffic on the British autobahn route; this was aimed at the military police patrols rather than at the traffic itself. Also in 1952 the USSR responded to the recent agreements between the Western Allies and the FRG by instructing the GDR to declare a 5 km ‘security zone’ along the inter-zonal border and

the

Baltic coast. East German civilians residing in the zone were ruthlessly evicted and resettled elsewhere.

The East Berlin uprising broke out on 16 June 1953, when building workers in the Stalinalee protested against a 10 per cent increase in production norms without any increase in pay, although when crowds gathered the next day the nature of the protest quickly changed from economic to political. The GDR’s

Volkspolizei

(National Police) were overwhelmed, and the Soviet army had to be called in to restore order. On 18 June the Western commandants sent a ‘strong protest’ to the Soviet commander, but there was little else they could do and it was all soon over. Thirty-five people were killed and 378 injured in the actual fighting, with an unknown further number executed or imprisoned by the GDR authorities afterwards.

Knowing of the shortage of food in the GDR, on 10 July 1953 President Eisenhower offered to supply $15 million worth of foodstuffs for the people. The offer was resisted by both the GDR and the Soviet governments, but the USA went ahead and set up supply depots in West Berlin, and some 3 million people from East Berlin and elsewhere in the GDR managed to collect at least one food parcel each.

The USSR handed over responsibility for borders and for civil traffic on the autobahns to the GDR on 21 January 1956; Soviet military-manned checkpoints were, however, retained for military traffic. The Western Allies protested, particularly when the GDR raised civil vehicle charges on the autobahns by between 100 and 1,000 per cent, and the increases were later reduced, but not eliminated.

On 27 November 1956 two US congressmen and the wife of one of them were visiting East Berlin when they were arrested and detained by the

Volkspolizei

. Not surprisingly, this caused immediate and strong US reactions, and the group was quickly released.

On 10 November 1958 Khrushchev made a speech in Moscow in the course of which he proposed that West Berlin should become a ‘Free City’, adding that if he failed to receive agreement within six months he would transfer all Soviet powers over West Berlin to the GDR. He then sent identical notes confirming this to the British, French and US governments on 27 November. This led to a new ‘Berlin crisis’, and there was some low-level harassment – for example, a US convoy was halted for two days at the Soviet checkpoint at Helmstedt (2–4 February 1959), and aircraft were also harassed in the corridors. The situation was further complicated in February 1959, when new passes for the Western missions to the Soviet commander-in-chief were issued in the name of the GDR. The Western Allies immediately protested, since the missions were accredited to the Soviet commander-in-chief in person, and demanded that the previous passes be reinstated, which they were. Finally, in this particular episode, Khrushchev’s six-month deadline arrived on 27 May 1959, but the Western

Allies

allowed it to pass without any response and the Soviets took no further action.

In the late 1950s the question of the 3,050 m ceiling in the air corridors became a major issue, as piston-engined airliners were being replaced by new types, powered by turboprops, which had an economical cruising altitude considerably in excess of that figure; the Viscount aircraft used by BEA, for example, normally flew at 4,250 m. In an effort to force the issue, on 27 March 1959 a US air-force C-130 Hercules transport flew towards Berlin at an altitude of 7,600 m along the southern corridor, where, to nobody’s surprise, it was buzzed by three Soviet fighters. Similarly, a US C-135 jet transport flying at 3,600 m on 3 April and another C-130 at 6,000 m on 15 April were both buzzed. These incidents led to bitter arguments over the 3,050 m maximum, which the Soviets said had become accepted by ‘custom and practice’. Eventually this maximum was accepted by President Eisenhower in person, who declared that it was not an issue worth going to war over.

Meanwhile, escape to West Berlin and West Germany was relatively easy, and the loss of people from the GDR was becoming such a serious problem that it was beginning to threaten the future of the state itself.

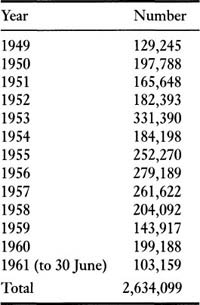

Table 32.1

shows the annual losses (mostly into West Berlin) since the end of the Berlin Airlift.

The Communist state’s problems were exacerbated when, in late 1959, the GDR started to collectivize the remainder of its privately owned farms; this proved to be an even more unpopular move than usual, but was nevertheless ruthlessly implemented. It was completed by mid-1960, resulting in at least 15,000 farmers fleeing to the West and, coupled with the inefficiencies always associated with collective farming, leading to yet another food crisis in the GDR that year. As a result, escapes to the West increased dramatically, reaching 30,000 in July 1961 and 20,000 in the first twelve days of August, with no less than 4,000 on 12 August alone.

Table 32.1

Numbers of People Escaping from the GDR