The Cold War: A MILITARY History (66 page)

The third element consisted of two counter-air strikes, in which NATO would launch attacks against 115 Warsaw Pact airfields in Czechoslovakia, East Germany and Poland. The Warsaw Pact air forces would launch a concurrent attack on 100 NATO airfields: forty in Belgium, France and the Netherlands, and sixty in West Germany.

Although none of these attacks was specifically aimed at cities, some of the bridges and airfields were inevitably located in such urban concentrations.

The Outcome

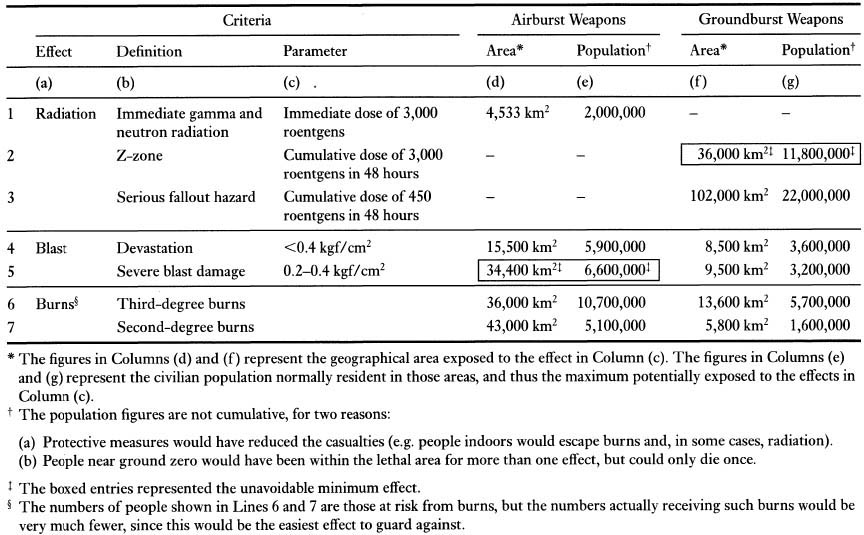

The predicted outcome of such a battle is shown in

Table 35.2

. The boxed entries represent the unavoidable minimum effects. Thus, under airburst weapons (columns (d) and (e)), the figures show the area of severe blast damage in which the population would suffer some 80 per cent deaths in the inner zone, reducing to 10 per cent in the outer zone. In the groundburst case (columns (f) and (g)), the boxed entries represent the ‘Z-zone’, where it would have been necessary to evacuate immediately those people who had survived the effects of blast and fire to areas with a small risk of fallout.

If all the nuclear weapons used in this battle had been groundburst, there would have been a serious fallout hazard over 138,000 km

2

of the total land mass of West Germany, of which 36,000 km

2

would have been the Z-zone, from which any survivors would have had to be evacuated if they were not to die. In addition, 3.6 million people would have been homeless, with another 3 million homes damaged.

If, however, the battle had been conducted using airbursts alone, there would have been no residual radiation, but the immediate radiation dose (3,000 roentgens) would have been delivered over an area which, in peacetime, housed some 2 million people.

Table 35.2

Summary of Effects of a Nuclear Attack on West Germany (area 248,640 km

2

; population (1960) 54.5 million)

It is important to note that these figures represented the areas affected by the stated hazard and the population within those area. Thus the population figures would not necessarily have been the total casualty figures, particularly in the case of immediate radiation, where a proportion of the population would have been indoors or possibly in shelters. Similarly, many people at risk from burns might have been protected by being indoors or even, if in the open, by being in the shadow of a building. Where blast is concerned, however, the case would have been different, since in the ‘blast devastation’ area (Lines 4–5) the homes of some 5.9 million people would have been reduced to rubble and those of a further 6.6 million severely damaged.

During the Second World War the German homeland was subjected to bombing attacks during a period of some five years, in which some 400,000 civilians were killed and a further 600,000 were injured. Cities were the main targets, and across the country as a whole some 10 per cent of the residential housing stock was destroyed and a further 10 per cent was damaged. In a nuclear war, far worse damage would have been caused in a matter of minutes than during the five years of the Second World War.

Whether the campaign had been conducted using airburst or ground-burst weapons the damage would have been massive. In the airburst case the damage would have been wrought mainly by blast, with the destruction of a large number of houses and factories, and with the probability of the death of many millions of people. In the groundburst case the blast effects would have been somewhat less, but the area of the Z-zone would have been about the same as for the airburst case and almost all the 11.8 million people within that zone would have died unless rapidly evacuated. In short, airbursts would have damaged more buildings, groundbursts would have caused more casualties to people.

fn1

In the early 1960s the author attended two separate study periods in Malaya on the conduct of nuclear war in the jungle. In the first, the basic assumption made by the team running the study was that nuclear weapons would have swept away vast swathes of jungle, making movement by both vehicles and men relatively easy. In the second, the opening assumption by a different team was that the nuclear weapons had created an impenetrable obstacle, making movement impossible.

fn2

From the mid-1970s onwards it was possible to retarget Minuteman missiles in flight, but it was not possible to terminate the flight.

fn3

JIGSAW was the (doubtless carefully chosen) acronym for the

J

oint

I

nter-Service

G

roup for the

S

tudy of

A

ll-out

W

arfare.

fn4

Note that JIGSAW gave radiation doses in roentgens and that, for the purposes of this book, the roentgen and the rad are synonymous – see the note on

see here

.

fn5

The second reason given in the paper is that the JIGSAW staff were advised by the director of military intelligence that ‘there was a lack of precise information on the location of Soviet forces in other areas of the USSR’. This is a most surprising admission at that stage of the Cold War.

fn6

This would have been some

eighty

times more powerful than the weapons dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

fn7

The European battle was based on the following assumptions:

1 The prevailing wind was 37km/h knots from the west.

2 In tactical areas and on the interdiction lines, the weapons were uniformly spaced and burst simultaneously.

3 Where blast pressures from separate explosions overlapped, the damage done was that caused by the higher overpressure only.

36

The Financial Cost

IF ACTUAL PHYSICAL

combat never broke out, there were nevertheless some real battlegrounds on which the Cold War was fought, among them those of equipment and of technology. But these depended upon the resources made available to finance them, and the management systems which controlled them. Indeed, there are good grounds for believing that NATO eventually priced the Warsaw Pact, and in particular the Soviet Union, out of business.

EQUIPMENT

All nations expended a substantial proportion of their defence budgets on equipment, and the Cold War was a ‘happy time’ for military men on both sides of the Iron Curtain, even though they constantly complained that they were short of money and starved of resources. The fact was that public funds had never been so generously lavished on military forces in peacetime, and many of the shortages were more apparent than real.

The naval, general and air staffs and the government procurement agencies alike faced many challenges, of which the most fundamental was that, in the worst case, the Third World War might have broken out very suddenly and then been both extremely violent and very short. This would have been quite unlike the First and Second World Wars, where there had been time to mobilize national industries, to develop new equipment, and to produce it all in sufficient quantities. But, whereas those wars had lasted four and six years respectively, the indications were that, in the worst case, the Third World War would have been over in a matter of months, perhaps even of weeks. Such a conflict would therefore have been fought with whatever was available at the time – a ‘come as you are’ war, as it was described at the time. In consequence, armed forces had to be constantly maintained at a state of high readiness, with their weapons, ammunition and equipment to hand – a

process

which proved difficult to sustain for forty years. A second problem was that the accelerating pace of science and technology, coupled with the lengthy development time for new equipment, meant that many weapons systems were obsolescent before they had even entered service.

Inside their respective pacts, the two superpowers enjoyed many advantages: their financial and industrial resources were huge in comparison to those of their allies, and their own forces were so large that they guaranteed a major domestic market for any equipment that was selected. They thus dominated their partners, and it proved a struggle for their European allies on either side of the Inner German Border to avoid being overwhelmed.

Even for the USA, however, military procurement was by no means smooth sailing. Enormous amounts of money were expended on systems which, for one reason or another, were cancelled before they reached service. One prime example was the effort devoted by the US air force to finding a successor to the Boeing B-52, to maintain its manned strategic bomber force. First there was the XB-70 Valkyrie hypersonic aircraft, which was followed by the B-1, the B-1A (which was virtually a new aircraft) and then the B-2. The sums expended on these aircraft for what was, in the end, very little return are almost incalculable. Further, quite what purpose such aircraft would have served in a nuclear war, apart from dropping H-bombs in gaps left by ICBMs and SLBMs, is not clear. The US army had some dramatic failures, too, such as the Sergeant York divisional air-defence system and the MBT-70 tank.

The US forces were certainly not alone in having problems. The Canadians, who had little enough money for defence, undertook three massive projects, which many contemporary observers warned were over-ambitious. The first was the all-Canadian Arrow fighter of the late 1950s, which reached the prototype stage before cancellation. The second, in the 1980s, was the submarine project which grew from three replacement diesel-electric submarines to twelve nuclear-propelled attack submarines; this reached an advanced stage, though short of orders being placed, before it was cancelled. The third, in the 1990s, was an order for over fifty Westland helicopters to replace ageing anti-submarine and general-purpose helicopters; this was summarily cancelled by a new government, and large compensation payments had to be made. These three projects incurred expenditure totalling hundreds of millions of dollars, but, in the end, there was not a single aircraft, submarine or helicopter to show for any of them.

The British suffered from two problems. The first was projects reaching an advanced stage and then being cancelled. This affected numerous aircraft, such as the Nimrod AWACS, the Vickers-Supermarine Swift fighter and the TSR-2 strike aircraft, while the navy suffered a similar fate with the CVA-01 aircraft carrier, as did the army with the SP70 self-propelled gun and the Blue Water battlefield missile. In addition, some of the projects that

did

reach service did so only after many years in development and the expenditure of great sums of money, when a viable foreign alternative was readily available at much lower cost.

This is not to deny that some excellent equipment was produced. In the USA, the Los Angeles-class SSNs and aircraft such as the B-52 bomber, F-86 Sabre, F-4 Phantom, F-15 Eagle and F-16 Fighting Falcon were world leaders in their day. Among British successes were the Canberra and Vulcan bombers, the Hunter fighter and the Harrier V/STOL aircraft, the Leander-class frigates and the Centurion tank. The Germans bought most of their aircraft from abroad, but on land their Leopard 1 and Leopard 2 tanks were outstandingly successful. The French produced some outstanding fighter aircraft in the Mirage series, which sold around the world.

Indeed, some European equipment was so good that it even found a market in the United States. The US air force, for example, purchased the British Canberra bomber, while the Marines ordered hundreds of Harrier V/STOL aircraft. In the 1980s the US army bought its most important communications system, RITA, from France, while its tank guns came first from the UK (105 mm) and subsequently from Germany (120 mm).

MANAGEMENT

All equipment-producing countries knew that their procurement processes were slow, overbureaucratic and inefficient, but, while all tried a considerable number of alternative methods, none of them ever found a real solution. Projects conducted with extreme speed and then rushed into production, such as the US army’s M47 and M48 tanks and the US air force’s F-100 Supersabre fighter in the 1950s, tended to result in equipment which was simply not ready for operational use and which required years of additional work to sort out the problems. On the other hand, projects which were conducted with extreme care could take over a decade to complete, by which time the technology was out of date, and the time taken ensured that they were very expensive.

Some observers advocated an escape from this by using an incremental approach, whereby a new weapons system was created by bringing together various in-service components. Using this approach, the Soviet army achieved a major success with its ZSU-23–4 air-defence gun, but when the US army tried to do the same thing with the Sergeant York system it proved to be a time-consuming and costly failure.

It should not, however, be thought that the USSR had a better system. Because of the secrecy which was inherent in Soviet equipment procurement, the West only ever saw the equipment which had passed through the development system and had been put into service, where it could no longer

be

hidden. There were, however, many projects which, despite considerable expenditure, never reached service status.