The Cold War: A MILITARY History (64 page)

By the early 1950s the production rate of atomic bombs had increased to the point where US field commanders – both air-force and navy – began to make plans for their use, each of them planning to use them in support of

his

battle. There was nothing in this situation to prevent several commanders from selecting the same target; indeed, a US Senate committee was told that in the Far East 155 targets had been listed by two commanders and 44 by three, while in Europe 121 airfields had been targeted by two commanders and 31 by three.

4

A first attempt at some form of co-ordination was made in a series of conferences held in the early 1950s, which achieved partial success. The situation came to a head, however, when the navy’s Polaris SLBMs and the air force’s Atlas ICBMs became operational in the early 1960s, and a Joint Strategic Target Planning Staff (JSTPS) was established, with an air-force lieutenant-general at its head but with a naval officer as his deputy. The first outcome of the JSTPS’ work was the Comprehensive Strategic Target List (CSTL), which identified 2,021 nuclear targets in the USSR, China and their satellites, including 121 ICBM sites, 140 air-defence bases, 200 bomber bases, 218 military and political command centres, 124 other military targets, and 131 urban centres.

5

This CSTL duly became an integral part of the first Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP), which was produced in December 1960.

There were no alternatives in this SIOP-60, which consisted of one massive nuclear attack, and it was one of the earliest targets for reform when President Kennedy took power in January 1961. US planners were now, however, aided by virtually complete satellite coverage of the USSR, giving them information on the potential enemy never previously available (and which, among other things, made it clear that the supposed ‘missile gap’ did not exist). This resulted in SIOP-63, which consisted of five categories of counter-force option: Soviet missile sites; bomber and submarine bases; other military targets; command-and-control centres; and urban–industrial targets. This received serious criticism from three separate quarters. First, from within the USA, because of what appeared to be a first-strike strategy; second, from the USSR, which denied the possibility of controlled counter-force warfare; and, third, from NATO allies, who were very alarmed by the total absence of any urban targets (the so-called ‘no cities’ strategy).

President Kennedy’s secretary of state for defense, Robert McNamara, then developed the concept of Assured Destruction, which he described in public first as ‘one-quarter to one-third of [the Soviet Union’s] population and about two-thirds of its industrial capacity’ and later as ‘one-fifth to one-fourth of its population and one-half to two-thirds of its industrial capacity’. Whatever was said in public, however, within the US armed forces SIOP-63 was not withdrawn, and thus there appears to have been a marked divergence between the public and the internal rhetoric.

Proponents of this policy of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) argued that the one way to make nuclear war impossible was to make it clear that any nuclear attack would be answered by a total attack on an enemy’s population, together with its industrial and agricultural base. While such a concept might have been valid in the early days of the nuclear confrontation, it rapidly lost its credibility when it became clear that, even after such a strike, the USSR would still have sufficient weapons to make a response-in-kind on US cities.

The strategy of ‘flexible response,’ introduced in 1967, required facing an opponent with a credible reaction which would to inflict losses out-weighing any potential gain. The deterrent power of such a strategy depended on the capacity of the proposed response to inflict unacceptable losses on the opponent, while its credibility depended upon its ability to minimize the risks of higher-order losses on the responder’s own country in subsequent rounds. This posed something of a dilemma, in that the deterrent power of the response was enhanced by escalation to a higher level, while credibility tended in the other direction, since a lower-level response carried no inherent escalatory risks. The plans implement this strategy were promulgated in a revised version of the SIOP which became effective on 1 January 1976.

It became customary for all incoming presidents to initiate a review of the strategic nuclear-war plans, and that carried out by President Jimmy Carter in 1977–9, was expected to result in major changes. In the event, however, it led only to a refinement of the previous plan, together with the introduction of rather more political sophistication. Thus, for example, targets were selected in the Far East, not so much for their immediate relevance to the superpower conflict, but because their destruction would make the USSR more vulnerable to attack by the People’s Republic of China.

A further review was conducted when the Reagan administration came to power in 1981. This resulted in a new version of the SIOP, which included some 40,000 potential targets, divided into Soviet nuclear forces; conventional military forces; military and political leadership command posts and communications systems; and economic and industrial targets, both war-supporting and those which would contribute to post-war economic recovery. The plan allocated these targets to a number of discrete packages, of differing size and characteristics, to provide the National Command Authority (the president and his immediate advisers) with an almost limitless range of options.

The new plan also included particular categories of target for other plans, for possible implementation on receipt of an unequivocal warning of a Soviet attack. These included a pre-emptive strike, launch-on-warning and launch-under-attack. The plan also included a number of ‘withholds’, but stipulated that a reserve of weapons must be retained for possible use against those ‘withholds’ if the developing scenario so dictated.

The real calculations of strategic nuclear war – known as ‘dynamic’ assessments – were extremely detailed and were far more complex than the static measurements. One such ‘dynamic’ calculation in the period following the Soviets’ fielding of the SS-18 resulted in an assessment that, under certain conditions, a Soviet counter-force first strike would appear to be a possibility. In this assessment it was calculated that the USSR, which normally had only about 10 per cent of its SSBN force at sea, would gradually, and covertly, increase that number, and, if the US command decided to ride out the attack, the Soviets would then destroy approximately 45 per cent of the US strategic forces. As a result, the ensuing US counter-military retaliatory strike on the Soviets (who would be on full alert) would leave the Soviets with 75 per cent of what had been left

after

their first strike. This meant that the USSR would retain not only a reserve capable of carrying out either an urban–industrial strike on US cities or an attack on US ‘other military targets’, but also a reserve for use against another opponent (the so-called ‘

n

th-country reserve’) – an outcome which would have been distinctly favourable to the Soviets. If the USA managed to launch all its ICBMs under attack, however, the damage ratio more or less reversed: 40 per cent

damage

to remaining Soviet forces versus 25 per cent damage to US strategic forces.

Thus, argued the US planners, a credible US launch-on-warning/launch-under-attack capability was a mandatory element of an effective deterrent. These results posed a problem encountered in numerous US war games: that neither side could enhance stability by pursuing its own best interests of a secure deterrent potential, but, conversely, neither side could unilaterally lower its deterrent. For the US to do the latter gambled on a US judgement of how the Soviets treated ‘uncertainty’ and what their perceptions of relative advantage might have been.

This whole area highlighted the decision to launch as one of the major problems associated with missiles. Launching bombers for possible nuclear missions was relatively easy, since crews were under firm instructions that they had to receive a positive (and encoded) order from the ground to continue before reaching specified waypoints, otherwise a return to base was mandatory. Missiles, on the other hand, received only one order – to take off; there was then no turning back.

fn2

Thus the decision to launch the missile was much harder to make.

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE HILL

As outlined above, the plans made by nuclear planners on both sides during the Cold War were primarily concerned with the dispatch of missiles and bombers. But what really mattered was what happened at the far end.

During the Cold War it was not particularly difficult to discover the effects of nuclear weapons on individuals, and official books such as

The Effects of Nuclear Weapons

6

were available on the open market. Numerous unclassified assessments of the effects of nuclear war were prepared by official bodies, such as the US Department of Defense and the US Office of Technology. Similar assessments were also prepared by private bodies, such as research departments and magazines, but all faced similar problems. First, truly detailed studies inevitably required considerable time and great computing power. Second, all study findings were extremely sensitive to the initial assumptions on questions such as the military attack plan, the choice of airbursts or groundbursts, and the assessment of civil-defence measures. Third, there was the inescapable fact that all studies were looking at a situation which included an almost endless series of imponderables for which no previous human experience provided a reasonable guide.

In the British Public Record Office, however, there is a series of once

highly

classified studies carried out between 1960 and 1962 by a body known as JIGSAW’,

fn3

a group of high-level experts which reported direct to the British Chiefs-of-Staff Committee and prepared a variety of reports on the possible outcomes of nuclear wars.

7

Since JIGSAW was working at such a high level, it can safely be assumed that its researches were thorough, that it obtained the most reliable expert inputs, and that the settings it considered were based on existing plans. The JIGSAW assessments can therefore be taken as being as authoritative as those of any other body, in the USA or the USSR.

A STRATEGIC ATTACK ON NORTH AMERICA

JIGSAW conducted a study of an attack on the United States and Canada which examined various aspects of an attack on cities. The first study assumed a Soviet attack on the 283 cities with a population exceeding 50,000 (1970 figures), each being hit by a single nuclear weapon, targeted on the geographical centre of the city. These attacks would have destroyed 30 per cent of the buildings and killed or rendered ineffective the total population of those cities, amounting to 81 million people. The study then looked at what would have happened to the remaining 149 million people in the other, smaller, urban areas and the countryside. It found that:

– Using 1 MT weapons, thirty-one million [people] would have been within the area of significant fallout, of whom some five million would have received a radiation dose of 200 roentgens or more, thus becoming casualties, while six million would have received between 50 and 200 roentgens, thus becoming ineffective.

– Using 8 MT weapons, the numbers within the area of significant fallout would have risen to seventy-nine million, of which twenty-one million would have received more than 200 roentgens, and seventeen million between 50 and 200 roentgens.

fn4

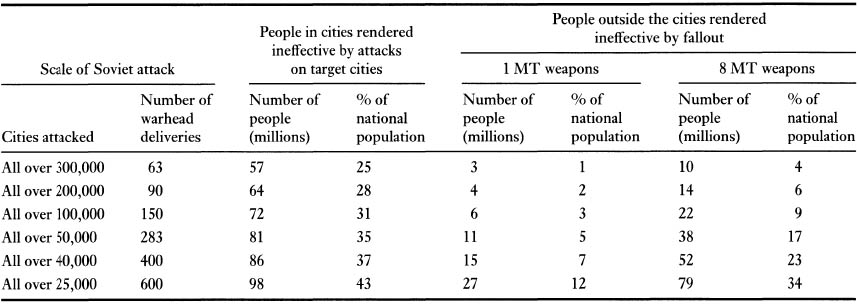

Next JIGSAW examined the effects of different scales of attack, from attacking the sixty-three cities with a population exceeding 300,000 to attacking all 600 cities with a population of 25,000-plus. It also compared the effects of attacks using all 1 MT weapons or all 8 MT weapons. The outcome is shown in

Table 35.1

. This shows that, for all levels of attack, the number of people rendered ineffective in the cities by blast and radiation was always greater than the number of those outside the cities rendered ineffective by fallout alone. It should, however, be noted that, as the weight of the attack increased, the number of rural fallout victims rose much more sharply than did the number of victims in the cities.

Table 35.1

JIGSAW Assessments of the Effects of a Soviet Attack on North America

A STRATEGIC ATTACK ON THE UK

When JIGSAW examined a strategic attack on the mainland UK (population 53 million) it had to modify its approach, since, compared to the USA and the USSR, the area was much smaller, and the 113 cities with a population of over 50,000 were much closer to each other. In fact, according to JIGSAW’s calculations, deliveries of 1 MT weapons on all these 113 cities would have resulted in the deaths of more than 90 per cent of the total population.

JIGSAW therefore examined an attack using twenty-five weapons: six on Greater London and one each on nineteen other cities. This would have rendered 33 million people in the target cities ineffective. For the remainder in smaller towns and rural areas: