The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (15 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

Â

On Golden Pond: Rome Conquers Italy and the Mediterranean

In This Chapter

- Struggles after the fall of the kings

- Rome establishes a powerful base in central Italy

- Expansion into central and southern Italy

- The Punic Wars with Carthage

- Roman conquests in the East and West

You can divide the roughly 500 years of the Roman Republic into three general sections:

- 500â270

B

.

C

.

E

.: Rome conquers Italy - 270â133

B

.

C

.

E

.: Rome conquers the Mediterranean - 133â20

B

.

C

.

E

.: Rome conquers everything else (including itself)

We'll save number three for Chapter 7, “Let's Conquer . . . Ourselves! The Roman Revolution and the End of the Republic.” Right nowâquick march!âwe've got a lot of territory to cover.

B

.

C

.

E

.)

The early Roman Republic had trouble with all its neighbors before all its neighbors had trouble with Rome. Etruscans, Gauls, and neighboring tribes made attempts on

Roman territory while Rome struggled with new political and social order. Often on the verge of defeat or internal collapse, Rome gained its feet and overcame both internal and external threats. As it did, Rome established itself as the chief power in central Italy and laid down the foundations for a great empire. Then it went on the offense and conquered the whole Italian peninsula. This, in turn, brought Rome into conflict with Greece and Carthage who also had major interests in southern Italy.

After the Tarquins were thrown out of Rome (see Chapter 5, “Seven Hills and One Big Sewer: Rome Becomes a City”), the leader of the Etruscan confederation, Lars Porsenna, attacked the city. Archeological evidence indicates that the Etruscans did reoccupy Rome for a time, but Roman tradition says that a number of heroic Romans kept them at bay. Here are a few of them, who became models for Roman valor:

- Horatius Cocles.

Horatius single-handedly blocked Porsenna's forces while the Romans were dismantling the wooden bridge over the Tiber, the

Pons Sublicius

. The sight of one man challenging and threatening their entire army stunned the Etruscans. They hesitated long enough to allow the bridge to be disassembled. Horatius then plunged, fully armed, into the Tiber and swam back to the cheering Romans. - Mucius Scaevola.

Mucius sneaked into the Etruscan camp and attempted to assassinate Porsenna. To show the Etruscan just what kind of people he was dealing with, Mucius stuck his hand in a fire and impassively let it burn. Porsenna was so impressed at his bravery that he let him go. According to Roman lore, this is how Mucius got the name Scaevola, which means “left-handed.” - Cloelia.

During the war, the Romans were forced to give hostages to the Etruscans. Among them was a young girl, Cloelia. Cloelia bravely escaped and swam the Tiber back to Rome. The Romans, who were the a-deal-is-a-deal kind of people, sent her back. Porsenna admired her courage and let her and some of the other hostages go.

Whether the Etruscans got into the city again or didn't, the Latin and Greek cities south of Rome were not about to let Etruscans reoccupy the territory. They attacked and defeated Porsenna's son, Arruns, and broke the Etruscan hold over Latium. Rome was once again free.

Peace didn't last long. Rome had been a powerful city and wanted to stay that way. The Latins, however, didn't want the same Rome under new management. Rome and the Latins went to war, which ended in 493

B

.

C

.

E

. with an important treaty called the

foedus Cassianum.

Rome and the Latin League (the coalition of Latin cities) contributed equally to the common defense, shared some citizen rights, and equally

divided the spoils of conquest (that is, Rome got half and the Latin League got half). This put Rome on a footing equal to the whole League and allowed Rome alone to summon the entire allied force.

The Latins, alarmed by continued Roman expansion after the First Samnite War (see “The Samnites and Central Italy” later in this chapter), revolted. Rome defeated the Latins in 338

B

.

C

.

E

and broke up the Latin League. In place of the league, it made Latin cities

municipiae

and established

colonae

among them. These strategies proved to be crucial for Rome's future success and strength.

Rome's arrangements with the individual Latin states required service to Rome but also gave the Latins rights and privileges as Roman citizens. Latin cities became

municipiae

(municipalities), from the Latin

munera,

which means “burden” (in this case, the burdens of citizenship). Several

municipiae

were completely incorporated into the Roman state, and although they maintained limited local autonomy, they received full Roman citizenship, including the right to vote and hold office (

civitas

). Other cities retained “Latin” status: more autonomy but without voting privileges (

civitas sine suffragio

).

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Two of Rome's successful strategies for ruling their conquests,

municipiae

and

colonae,

have come down to us in the words “municipality” and “colony.”

Municipiae

had to defer to Rome in foreign policy and supply troops when called. Municipal citizens could intermarry and hold contracts with Romans but not among themselves. These arrangements tied the Latins' social and economic status, power, and identity to Rome. The Romans used this model as they conquered the rest of their empire and as they established colonies.

Colonae,

or colonies, were new settlements established with surplus population. Ancient states had established colonies for centuries, but the Romans made a studied policy of it after 338

B

.

C

.

E

. As they conquered territory, they established colonies in important strategic and economic locations. The status of these colonies mirrored the status of

municipae:

Their citizens received full Roman rights. “Roman” colonies were small defensive outposts in difficult locations. “Latin” colonies were large enough to be viable on their own and had the status of other Latin

municipiae.

Both Romans and Latins could belong to either kind of colony.

Etruscan power declined in the period after losing Rome leaving the entire region unstable. Rome faced constant threat from neighbors competing for territory: the Volsci in the south, the Aequi in the east, and the Etruscan city of Veii about 12 miles to the north.

The Hinerci were a people sandwiched between the Aequi and Volsci. The Romans followed a policy of

di-vida et impera

(divide and rule) and formed an alliance with the Hinerci against the other two. This kept the Aequi and Volsci from uniting during the years of fierce fighting between Rome and these tribes. To the north, Rome eventually conquered Veii by tunneling under its walls in 396

B

.

C

.

E

. This was a great victory for Rome, and the first in a long line of successful military operations.

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

The Roman hero of this period was Cincinnatus. With a Roman army pinned down by the Aequi, the senate called upon Cincinnatus to save them. They found him plowing in his small field, and made him dictator (emergency commander). Cincinnatus put down the plow, led an army, defeated the Aequi, returned to his farm, and picked up the plow again. He became a symbol for the Roman ideals of military service, frugality, and simplicity.

The Gallic Avalanche

Â

When in Rome

Rome actively sought to keep potential enemies from forming united opposition by exploiting rivalries and by keeping relationships with Rome individual and separate. In this way opposition was kept fragmented and isolated. This strategy was called

divida et impera,

or “divide and rule.”

Gallic tribes, under the pressures of population growth and the invasions of Germanic peoples from the north, had poured over the Alps in search of pasture and plunder since the sixth century

B

.

C

.

E

. In 390

B

.

C

.

E

., a Gallic army reached the river Allia (about 10 miles north of Rome) and met the Roman force. The Romans were used to fighting with spears in a disciplined and organized phalanx. But the Gauls, fierce warriors with big swords, just ran or rode up on them from every side! The Romans were completely routed.

Back in Rome, people fled the city. A few remained on the Capitoline hill, and tradition says that the old noble men remained in their halls in silent dignity. The Gauls, when they entered to plunder the halls, thought that the men were marvelous statuesâuntil one pulled a Roman's beardâthen they killed them all. The Gauls tried to capture the Capitoline, but geese kept as sacred to the goddess Juno started to honk as the Gauls crept up the hill and thwarted the attack. Finally, after plundering

the city and being paid a huge ransom, the Gauls left and headed back to the north where they had other fish to fry.

The defeat badly weakened Rome. This is when the Aequi and Volsci began to attack, the Latins began to revolt, and things looked pretty bleak for Rome's future. But the Romans rebuilt their city defenses, defeated their enemies, recaptured their territory, settled the affairs with the Latins, and went on to bigger things.

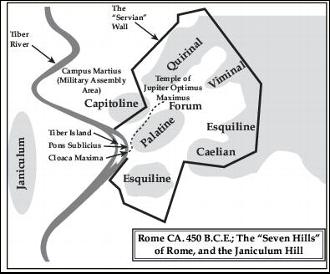

Rome and Italy, ca 450

B.C.E.

Rome's next major conflict was with the Samnites, the fierce mountain tribes of south-central Italy. These tribes lived in a loose federation of highland villages and towns. Roman and Latin colonies had encroached on their territory at the same time as the Samnites themselves were expanding and brought on a series of conflicts called the Samnite Wars.