The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (50 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

Two important figures illustrate the power of the times struggles between east and west and between barbarian and Roman forces. The first is Stilicho, a Vandal who became

Magister Militum

under Theodosius the Great. The second is Alaric, the great king of the Visigoths.

Stilicho married Theodosius's niece, Serena, and was entrusted by Theodosius with the fortunes of the young heirs Arcadius and Honorius. Stilicho became Honorius's regent in the west, but fostered imperial ambitions of his own, including plans for his son to marry Gallia Placidia, a patron of churches, and his daughter to marry Honorius.

Â

When in Rome

The

Magister Militum

, or “Master of the Soldiers,” was the military title for a supreme commander (under the emperor) of both infantry and cavalry.

His ambitions conflicted with those of Rufinus, one of the high officials in the court of the boy emperor Arcadius in the east. Rufinus and Stilicho began to seek advantage over each other's half of the empire and to gain possession of Illyria, ostensibly in the name of their respective emperors. But before the two sides could deal directly with each other, they had to deal with the Visigoths, who were rebelling under Alaric.

Alaric was a king of the Visigoths who had been allowed to settle on Roman lands by Theodosius. Since then, the Visigoths had helped to defend the Empire against other barbarian invaders and felt poorly paid in return. Alaric rebelled and plundered almost to Constantinople itself, but was captured by Stilicho in 395. He was ordered released, however, by Arcadius (on Rufinus's advice) and allowed to regain his strength. Alaric then left Constantinople alone and led this army south on a swath of destruction down through the central empire into Greece. Stilicho finally arranged Rufinus's assassination in 395, but by then, the eastern empire feared his power. When Stilicho intervened and attacked Alaric's forces in 397, Constantinople declared Stilicho a public enemy for interfering outside of his jurisdiction.

After Rufinus's death in 395, the eunuch Eutropius, Arcadius's chamberlain, ran the eastern government in Arcadius's name and continued to deploy Alaric against Stilicho and Honorius. He gave Alaric a high command, and in 401, the Visigoths invaded Italy. They had Honorius cornered in Milan, away from the safety of Ravenna, but Stilicho brought his forces down from the north and captured Alaric's family. Alaric's forces withdrew but invaded again in 403. Again Stilicho defeated him, but the enormous invasions along the northern borders meant Stilicho could not stay. Alaric invaded Italy again in 407, demanding a huge tribute and employment for his army. This time Stilicho persuaded the Roman senate to accept the terms. Anger in Rome over the terms fueled the suspicion that this time Stilicho and Alaric might be working together and led to Stilicho's arrest and execution by Honorius in 408.

Barbarians in the Gates: Alaric and the Sack of Rome

Â

Roamin' the Romans

Gallia Placidia, half-sister of Honorius and Arcadius and mother of Valentinian III, was a patron of churches such as the basilica of St. Paul Outside-the-Walls in Rome and the Church of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem. During a voyage, a storm threatened to sink the ship with her and her children (Valentinian III and Honoria) on board. Placidia made an “Oh Lord, if you save me I will . . .” vow. You can read about it on the dedicatory inscription of the Church of the Holy Cross in Ravenna.

With Stilicho dead, Honorius reneged on his bargain with Alaric. Alaric was not amused and laid siege to Rome. The Romans agreed to pay him a huge ransom to

stop, but when he did, Honorius backed out before payment was made, and Alaric resumed the siege in 409. Finally, the Romans, mostly the pagans who had opposed the outlawing of their traditions and practices, elected another emperor and established a new administration with Alaric as commander.

As Honorius waffled as to what to do about his Roman rebellion, Alaric tried to play both sides against the middle. He agreed to dump the Romans and side with Honorius, but a rival barbarian leader came over to Honorius first. This left Alaric out of favor with both sides again. Alaric then turned his forces on Rome and sacked the city in 310. For three days, the Visigoths pillaged and burned, and when they left, they took a bundle of loot and Honorius's sister, Gallia Placidia, with them and marched south. Alaric, however, was not long for this world. He died on the way but received a fitting burial: His people diverted a river, buried Alaric under the bed, and turned the river back into its channel to hide and protect his grave. True or not, it's a great story!

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Alaric's conquest of Rome brought about a great “We told you so” outcry from the pagans of Rome. The statue of Victory had been removed, pagan rites were forbidden, and then, for the first time in 800 years, Rome was sacked. It appeared clear that the gods had abandoned Rome because Rome had abandoned the gods. The power of this sentiment compelled Augustine's 14-year effort to reconsider and recast history in his late, great work,

The City of God.

Augustine became the bishop of the North African city of Hippo, where he died in 430 just as it was about to fall to the Vandals.

In Alaric's place, the Visigoths elected Athaulf, who married the kidnapped Placidia (with her consent). It's actions like these that show that the Gothic tribes' bottom-line aim in engaging Rome was not plunder, but incorporation into the empire. Honorius and the in-laws responded by sending Stilicho's replacement, Constantius, with an army instead of wedding gifts. They cornered the Visigoths in Spain and got Placidia back. Honorius settled the Visigoths under Athaulf's successor, Vallia, as an independent nation within the province of Aquitania (west-central France, modern Gascony). Vallia's successor, Theodoric I, eventually became king of the entire province.

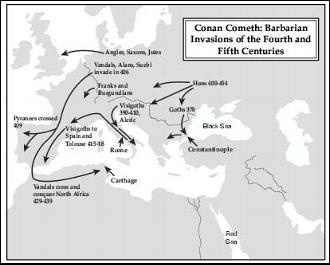

In the late fourth and fifth centuries, the northern Roman borders from the Black Sea to the North Sea were awash in barbarian migrations, invasions, and dislocations. Barbarian tribes took advantage of Roman disorganization and weakness in the west, but they also were being pushed from behind by the rapid encroachment of the Huns. As tribes poured across the borders, they tended to settle down (after a suitable amount of pillage) and become federated allies of Rome. These former invaders allied with Rome to defeat Attila and save Europe from the Huns, but by then the western empire had become a patchwork of barbarian kingdoms. The western imperial family (and later the popes) tried to manipulate these kings against each other for their own purposes, and the kings did the same in return.

Conan cometh: the barbarian invasions.

Okay. We've already talked in various chapters about “barbarians,” such as tribes of Gauls, Germans, Visogoths (Eastern Goths) and Ostrogoths (Western Goths). So were these new invaders more of the same? Well, yes and no. Some of the barbarian invasions of this period were Gallic and Germanic tribes though different tribes from previous centuries. Others came from as far away as central Asia. Here are the most important tribes to be familiar with for understanding the fourth and fifth century invasions:

- Angles, Saxons, and Jutes.

These Germanic tribes lived along the North Sea in what is now Denmark and northwest Germany. Their raids on Britain in the fifth century led to invasions in 408 and settlements that drove the Romans out of Britain for good in 442. - Franks and Burgundians.

These peoples invaded across the Rhine in 406 to 407. At first fought by the Romans, they eventually settled parts of Gaul and became autonomous but federated allies that helped the Romans defeat Attila and the Huns in 451. - Vandals, Alans, and Suevi.

These people came from a swath of territory extending from about Mainz, Germany, east through Hungary. They invaded across the Rhine at Mainz in 406 and made their way down through central France and across the Pyranees into Spain by 409. There they were partially contained by a combined force of Romans and Visigoths, who had gotten to the area first under Alaric and Athaulf.A particularly ambitious group of Vandals under king Gaeseric invaded across the Straits of Gibraltar in 428 and conquered all of North Africa, Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica. Gaeseric sacked Rome again in 455 and carried off Valentinian III's widow, Eudocia, and two daughters. The eldest, Eudocia, married Gaesaric's eldest son, Huneric, but the Vandals remained an outlaw nation until the eastern emperor Zeno recognized their legitimacy in 476. By then, however, the west was over.

- The Huns.

These were a fierce nomadic people and tremendous cavalrymen, who originated in central Asia. They pressured the Ostrogoth and Alan kingdoms, and under their king, Rua, became powerful enough to exact a yearly payoff of 350 pounds in gold from Theodosius II to keep them away. Rua and the Huns were particularly helpful to Aetius in his attempts to maintain power over the west and over the imperial family.Rua's nephew, Attila, succeeded him in 434 and turned the Huns into an empire. He was encouraged by the Vandal king Gaiseric to attack the Visigoths, and by Valentinian III's sister, Honoria, to attack Europe and establish himself, and her, with an empire of their own. Attila's forces got as far as Orleans, but had to turn back in 451. On the Mauriac Plain, a combined force of federated barbarians and the Roman army under Aetius fought Attila's army to a draw. Attila then attacked Italy to demand Honoria, but was turned back by the plague, the arrival of an army from the east, and the intervention of Pope Leo. He died in 454 while settling for marriage to Burgundian royalty.

After Stilicho and Alaric, the heirs of Theodosius struggled for position and control of the west. Constantius married Gallia Placidia. Their child, Valentinian III, became a threat to Honorius' position, so mother and child saw to their protection and took refuge with Theodosius II until Honorius's death in 423. By the time Theodosius decided to install the six-year-old Valentinian III as emperor, a certain “John” had been proclaimed emperor at Ravenna with the support of the general Aetius. In sorting it all out, Gallia Placidia became Regent, the six-year-old Valentinian III became Emperor, and Aetius became

Magister Militum

(Supreme Commander).

For the next 20 years, Aetius managed to control the imperial family and play off the various barbarian warlords against each other. His masterful management of the western empire has led some to call him “the last of the Romans.” Aetius's close ties with the Huns, among whom he had lived as a young man as a hostage, helped him greatly. His defeat of Attila in 451 brought him still greater power, to the resentment of Gallia Placidia and Valentinian III. Even though Aetius's son had married Valentinian's daughter, mother and son conspired with a powerful Roman senator, Potronius Maximus, to lure Aetius to a meeting in 454. There Valentinian himself killed Aetius, who was the last “Roman” with the power and skill to keep the west together.

Looking down on the ruins of the ancient forum and the remains of the Basilica of Maxentius where Constantine's colossal statue once stood.

When Valentinian didn't give Maximus the position he expected (namely Aetius's), Maximus conspired with Aetius's officers and assassinated Valentinian in 455. Maximus attempted to establish himself as emperor by marrying Valentinian's widow, Eudoxia, and her daughter, Eudocia, to his son. However, Gaeseric (king of the north African Vandals) had arranged for

his

son to marry Eudocia. This explains what brought the Vandals to Rome that year and why, besides their plunder, they carried both Eudoxia and Eudocia back to Africa with them.

And Maximus? He was killed by a stone thrown at him while he fled the attack. The house of Theodosius was over in the west; it was up to the barbarians now.