The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (48 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

Constantine's last plans were to conquer the Persian Empire and Christianize it. He grew ill along the way, died in Ankyrona in 337, and was buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles at Constantinople (much to the Romans' dismay). He left to his three sons an empire completely transfigured and transformed into a theocratic state. Constantine was fittingly both the first Christian emperor and the last deified by pagan Rome. The trinity of the sons, however, was unable to maintain the unity of the father until one became the

dominus

if no longer a

deus.

The Least You Need to Know

Â

When in Rome

In a

theocracy

the state is ruled by a god, or by an authority thought to be divinely guided and ruling in the god's name.

- Diocletian promoted the divinity of the emperor in a program to unify the Empire.

- Diocletian established a tetrarchy that ruled effectively as long as he remained active.

- After Diocletian's retirement, the tetrarchy fell apart until Constantine the Great unified the Empire again.

- Constantine maintained many of Diocletian's reforms but transformed the Empire into a Christian, not pagan, theocratic state.

Â

Barbarians at the Gates: The Fall of the Western Empire

In This Chapter

- Dissolution after the death of Constantine

- Upheavals in the Empire and culture from Julian to Theodosius II

- The barbarian hordes

- The “fall” of the western half of the Empire

Constantine's motto of “one ruler, one Empire, one creed” didn't outlive him. The Empire split into east and west, and no one creed held either together. Things were, at least for the western half, on the downhill side as a landslide of barbarians surged across the borders. As you now understand, barbarian invasions had been going on for a millennium. Nevertheless, something “Roman” had previously been able to rise up through the new layer, break it down through conquest and assimilation, and re-grow. But after Constantine, the waves were too great, too frequent, and too deep.

Rome, the city, was buried under the barbarian avalanche with little more than the trappings of an illustrious history and a few churches protruding. A wild western forest of Frankish, German, Vandal, and Ostrogoth stock grew up, away from, and often in opposition to “Roman” Constantinople. Eventually, the barbarian kingdoms matured and nourished, based on the old Rome, the hopes of empires to come, which were only marginally “Holy” or “Roman.”

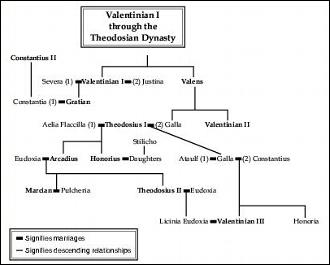

Constantine left the Empire with many possible heirs but without a succession plan. After initial bloodletting in which most of Constantine's half-brothers and their families were killed, rule of the Empire passed to his three sons by Empress Fausta.

Constantine II (337â340) took the prefecture of Gaul, Constans I (337â350) took the prefecture of Italy and Illyria, and Constantius II (337â361) took the prefecture of the east. Constantine II (the eldest) was supposed to have greatest authority, but you know how it goes with brothers in one room. Constans I kept putting his toe (so to speak) into Constantine II's side, and in 340, big brother came into Italy to teach Constans a lesson. Constantine, however, was killed, and Constans got the prefecture of Gaul instead of a lesson.

The Roman Empire after Constantine.

This arrangement lasted until Constans was assassinated in 350 and replaced by his general, Magnentius. Constantius II was having problems fighting the Persians in the east, but he was not about to let Magnentius usurp two-thirds of the Empire. He defeated Magnentius in 351, and by 353, the whole Empire was back under the rule of one emperor.

Constantius was a moderate Arian (see Chapter 17, “Divide and [Re]Conquer: Diocletian to Constantine,” for a discussion of Arianism) and encouraged the church to incorporate doctrinal differences. Beyond Christianity, he was less open-minded. He further Christianized the state against paganism and kept his father's ban on pagan temples and sacrifices.

Constantius was indecisive and suspicious, which led him to be manipulated by people in the imperial household, bureaucracy, and church. His temperament played out when he appointed Gallus, one of two remaining sons of Constantine's half-brother Julius, as Caesar in the east. Constantius surrounded him with his own people, and when Gallus turned out to be mildly successful and a potential rival, had him beheaded.

Trouble in both Gaul and Illyria meant Constantius was needed in two places at one time. He recalled Julian, Gallus's 23-year-old brother, from his studies in Athens, named him Caesar, and sent him to Gaul.

Julian turned out to be an intelligent, likeable, and successful commander. He restored the borders, won some spectacular victories, and became endeared to the people and army for limiting the abuses of Roman officials. This didn't sit well either with the officials, who denounced him to Constantius, or with Constantius, who feared Julian's growing popularity. He commanded Julian's troops to fight in the east, but Julian refused to send them. This made him even more popular with the local legions and their families. They proclaimed Julian “Augustus” in 360.

Â

When in Rome

Remember that the Christian

Church

of this period saw itself as a whole: It was organized under bishops and guided through the decisions of councils, such as the council of Nicea. Organized sects and denominations were, for the most part, a later phenomenon: Eastern and Western Orthodox churches, for example, didn't formally split until 1054.

Julian protested the proclamation (so he said), tried to negotiate with Constantius (who was having none of this), and then marched out to meet Constantius, who was already headed his way, in battle. But Constantius died along the way without leaving an heir. Julian became the sole emperor.

Julian was raised a Christian, but his studies and the fact that his entire family had been murdered by Christians combined to bring him back to traditional pagan values. He declared himself to be a pagan and rescinded laws against non-Christian practices. Julian was a prolific writer, and many of his works survive. Although he claimed freedom for religion and tolerance for Christianity, he attempted to advance a kind of official Neoplatonic paganism as a state religion in its place.

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Julian remains a controversial figure today. He still remains, to some, the apostateâto others, the vilified, if outdated, pagan and intellectual who attempted to roll back Christianity's hold on Rome.

Â

When in Rome

Neoplatonism

was the most influential pagan philosophy of late antiquity, and was a complicated synthesis of philosophic and spiritual teachings. It not only influenced early Christian theologians (like Augustine), but also Medieval and Renaissance thinkers and writers.

Â

When in Rome

Pagan

comes from the Latin

paganus

, meaning “country peasant,” and stems from Christianity being mostly an urban phenomenon in which the country dwellers (the

pagani

) were the last to convert. The same is true of the term “ heathen,” which refers to the primitive dwellers who lived in the wild “heaths” of Europe and England.

Julian authored significant administrative and tax reforms, and gave the Jews permission to rebuild the temple in Jerusalem, but his promotion of pagan ways met with outrage and resistance among the Christian communities that had thought the church triumphant. They termed him “the apostate,” or “ backslider.” This was particularly true in Antioch, from which Julian mounted an attack upon Persia. Antioch was heavily Christianized in politics and religion, and Julian's efforts there met with rejection.

A spear, reportedly thrown by one of his own Christian soldiers, wounded Julian during the campaign against Persia, and he died shortly thereafter. He remains a controversial figure todayâstill the apostate to some, the vilified pagan intellectual to others.

Julian's demoralized army, hounded by the Persians as they retreated, elected another commander, Jovian, as emperor. Jovian was a moderate Christian. He rescinded Julian's edicts and negotiated a settlement (a very bad one) with the Persians before he died just eight months later.