The Complete Yes Minister (54 page)

I pointed out that the Cabinet will be in favour of Hacker’s proposal. But we agreed that we could doubtless get the Cabinet to change their minds. They change their minds fairly easily. Just like a lot of women. Thank God they don’t blub.

[

Appleby Papers 37/6PJ/457

]

Appleby Papers 37/6PJ/457

]

[

It is interesting to compare Sir Humphrey’s self-confident account of this luncheon with the notes made by Sir Arnold Robinson on Sir Humphrey’s report, which were found among the Civil Service files at Walthamstow – Ed

.]

It is interesting to compare Sir Humphrey’s self-confident account of this luncheon with the notes made by Sir Arnold Robinson on Sir Humphrey’s report, which were found among the Civil Service files at Walthamstow – Ed

.]

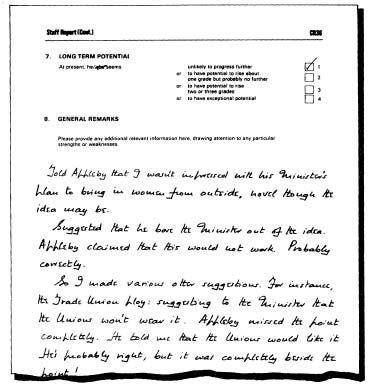

Told Appleby that I wasn’t impressed with his Minister’s plan to bring in women from outside, novel though the idea may be.

[

‘Wasn’t impressed’ would be an example of Civil Service understatement. Readers may imagine the depth of feeling behind such a phrase. The use of the Civil Service killer word ‘novel’ is a further indication of Sir Arnold’s hostility – Ed

.]

‘Wasn’t impressed’ would be an example of Civil Service understatement. Readers may imagine the depth of feeling behind such a phrase. The use of the Civil Service killer word ‘novel’ is a further indication of Sir Arnold’s hostility – Ed

.]

Suggested that he bore the Minister out of the idea. Appleby claimed that this would not work. Probably correctly.

So I made various other suggestions. For instance, the Trade Union ploy: suggesting to the Minister that the Unions won’t wear it. Appleby missed the point completely. He told me that the Unions would like it. He’s probably right, but it was completely beside the point!

I also suggested pointing the Minister’s wife in the right direction. And suggested that we try to ensure that the Cabinet throws it out. Appleby agreed to try all these plans. But I am disturbed that he had thought of none of them himself.

Must keep a careful eye on H.A. Is early retirement a possibility to be discussed with the PM?

A.R.

[

Naturally, Sir Humphrey never saw these notes, because no civil servant is ever shown his report except in wholly exceptional circumstances

.

Naturally, Sir Humphrey never saw these notes, because no civil servant is ever shown his report except in wholly exceptional circumstances

.

And equally naturally, Hacker never knew of the conversation between Sir Arnold and Sir Humphrey over luncheon at the Athenaeum

.

.

It was in this climate of secrecy that our democracy used to operate. Civil servants’ word for secrecy was ‘discretion’. They argued that discretion was the better part of valour – Ed

.]

.]

[

Hacker’s diary continues – Ed

.]

Hacker’s diary continues – Ed

.]

November 1st

Sir Humphrey walked into my office today, sat down and made the most startling remark that I have yet heard from him.

‘Minister,’ he said, ‘I have come to the conclusion that you were right.’

I’ve been nothing but right ever since I took on this job, and finally, after nearly a year, it seemed that he was beginning to take me seriously.

However, I was immediately suspicious, and I asked him to amplify his remark. I had not the least idea to which matter he was referring. Of course, asking Humphrey to amplify his remarks is often a big mistake.

‘I am fully-seized of your ideas and have taken them on board and I am now positively against discrimination against women and positively in favour of positive discrimination in their favour – discriminating discrimination of course.’

I think it was something like that. I got the gist of it anyway.

Then he went on, to my surprise: ‘I understand a view is forming at the very highest level that this should happen.’ I think he must have been referring to the PM. Good news.

Then, to my surprise he asked why the matter of equal opportunities for women should not apply to politics as well as the Civil Service. I was momentarily confused. But he explained that there are only twenty-three women MPs out of a total of six hundred and fifty. I agreed that this too is deplorable, but, alas, there is nothing at all that we can do about that.

He remarked that these figures were an indication of discrimination against women by the political parties. Clearly, he argued, the way they select candidates is fundamentally discriminatory.

I found myself arguing in defence of the parties. It was a sort of reflex action. ‘Yes and no,’ I agreed. ‘You know, it’s awfully difficult for women to be MPs – long hours, debates late at night, being away from home a lot. Most women have a problem with that and with homes, and husbands.’

‘And mumps,’ he added helpfully.

I realised that he was sending me up. And simultaneously trying to suggest that I too am a sexist. An absurd idea, of course, and I told him so in no uncertain terms.

I steered the discussion towards specific goals and targets. I asked what we would do to start implementing our plan.

Humphrey said that the first problem would be that the unions won’t agree to this quota.

I was surprised to hear this, and immediately suggested that we get them in to talk about it.

This suggestion made him very anxious. ‘No, no, no,’ he said. ‘No. That would stir up a hornet’s nest.’

I couldn’t see why. Either Humphrey was paranoid about the unions – or it was just a ploy to frighten me. I suspect the latter. [

Hacker was now learning fast – Ed

.]

Hacker was now learning fast – Ed

.]

The reason I suspect a trick is that he offered no explanation as to why we shouldn’t talk to the union leaders. Instead he went off on an entirely different tack.

‘If I might suggest we be realistic about this . . .’ he began.

I interrupted. ‘By realistic, do you mean drop the whole scheme?’

‘No!’ he replied vehemently. ‘Certainly not! But perhaps a pause to regroup, a lull in which we reassess the position and discuss alternative strategies, a space of time for mature reflection and deliberation . . .’

I interrupted again. ‘Yes, you mean drop the whole scheme.’ This time I wasn’t asking a question. And I dealt with the matter with what I consider to be exemplary firmness. I told him that I had set my hand to the plough and made my decision. ‘We shall have a twenty-five per cent quota of women in the open structure in four years from now. And to start with I shall promote Sarah Harrison to Dep. Sec.’

He was frightfully upset. ‘No Minister!’ he cried in vain. ‘I’m sure that’s the wrong decision.’

This was quite a remarkable reaction from the man who had begun the meeting by telling me that I was absolutely right.

I emphasised that I could not be moved on this matter because it is a matter of principle. I added that I shall have a word with my Cabinet colleagues, who are bound to support me as there are a lot of votes in women’s rights.

‘I thought you said it was a matter of principle, Minister, not of votes.’

He was being too clever by half. I was able to explain, loftily, that I was referring to my Cabinet colleagues. For me it

is

a matter of principle.

is

a matter of principle.

A very satisfactory meeting. I don’t think he can frustrate me on this one.

November 2nd

Had a strange evening out with Annie. She collected me from the office at 5.30, because we had to go to a party drinks ‘do’ at Central House.

I had to keep her waiting a while because my last meeting of the day ran late, and I had a lot of letters to sign.

Signing letters, by the way, is an extraordinary business because there are so many of them. Bernard lays them out in three or four long rows, all running the full length of my conference table – which seats twelve a side. Then I whiz along the table, signing the letters as I go. It’s quicker to move me than them. As I go Bernard collects the signed letters up behind me, and moves a letter from the second row to replace the signed and collected one in the first row. Then I whiz back along the table, signing the next row.

I don’t actually read them all that carefully. It shows the extent of my trust for Bernard. Sometimes I think that I might sign absolutely anything if I were in a big enough hurry.

Bernard had an amusing bit of news for me today.

‘You remember that letter you wrote “Round objects” on?’ he asked.

‘Yes.’

‘Well,’ he said with a slight smile, ‘it’s come back from Sir Humphrey’s office. He commented on it.’

And he showed me the letter. In the margin Humphrey had written: ‘Who is Round and to what does he object?’

Anyway, I digress. While all this signing was going on, Annie was given a sherry by Humphrey in his office. I thought it was jolly nice of him to take the trouble to be sociable when he could have been on the 5.59 for Haslemere. Mind you, I think he likes Annie and anyway perhaps he thinks it’s politic to chat up the Minister’s wife.

But, as I say, Annie and I had a strange evening. She seemed rather cool and remote. I asked her if anything was wrong, but she wouldn’t say what. Perhaps she resented my keeping her waiting so long, because I know she finds Humphrey incredibly boring. Still, that’s the penalty you have to pay if you’re married to a successful man.

[

A note in Sir Humphrey’s diary reveals the true cause of Mrs Hacker’s disquiet – Ed

.]

A note in Sir Humphrey’s diary reveals the true cause of Mrs Hacker’s disquiet – Ed

.]

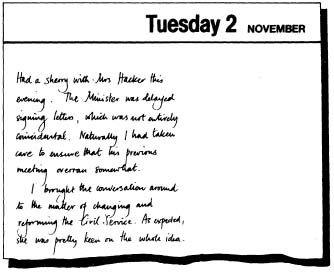

Had a sherry with Mrs Hacker this evening. The Minister was delayed signing letters, which was not entirely coincidental. Naturally I had taken care to ensure that his previous meeting overran somewhat.

I brought the conversation around to the matter of changing and reforming the Civil Service. As expected, she was pretty keen on the whole idea.

Immediately she asked me about the promotion of the Harrison female. ‘What about promoting this woman that Jim was talking about?’

I talked about it all with great enthusiasm. I said that the Minister certainly has an eye for talent. I said that Sarah was undoubtedly very talented. And thoroughly delightful. A real charmer.

I continued for many minutes in the same vein. I said how much I admired this new generation of women civil servants compared with the old battle-axes of yesteryear. I said that naturally most of the new generation aren’t as beautiful as Sarah, but they all are thoroughly feminine.

Mrs Hacker was becoming visibly less enthusiastic about Sarah Harrison’s promotion, minute by minute. She remarked that Hacker had never discussed what Sarah looked like.

I laughed knowingly. I said that perhaps he hadn’t noticed, though that would be pretty hard to believe. I laid it on pretty thick – made her sound like a sort of administrative Elizabeth Taylor. I said that no man could fail to notice how attractive she was,

especially

the Minister, as he spends such a considerable amount of time with her. And will spend even more if she’s promoted.

especially

the Minister, as he spends such a considerable amount of time with her. And will spend even more if she’s promoted.

My feeling is that the Minister will get no further encouragement from home on this matter.

[

Appleby Papers 36/RJC/471

]

Appleby Papers 36/RJC/471

]

[

Sir Arnold Robinson and Sir Humphrey Appleby were plainly quite confident, as we have already seen, that they could sway a sufficient number of Hacker’s Cabinet colleagues to vote against this proposal when it came before them

.

Sir Arnold Robinson and Sir Humphrey Appleby were plainly quite confident, as we have already seen, that they could sway a sufficient number of Hacker’s Cabinet colleagues to vote against this proposal when it came before them

.

The source of their confidence was the practice, current in the 1970s and 1980s, of holding an informal meeting of Permanent Secretaries on Wednesday mornings. This meeting took place in the office of the Cabinet Secretary, had no agenda and was – almost uniquely among Civil Service meetings – unminuted

.

.

Permanent Secretaries would ‘drop in’ and raise any question of mutual interest. This enabled them all to be fully-briefed about any matters that were liable to confront their Ministers in Cabinet, which took place every Thursday morning, i.e. the next day. And it gave them time to give their Ministers encouragement or discouragement as they saw fit on particular issues

.

.

Fortunately Sir Humphrey’s diary reveals what occurred at the Permanent Secretaries’ meeting that fateful Wednesday morning – Ed

.]

.]

I informed my colleagues that my Minister is intent on creating a quota of twenty-five per cent women in the open structure, leading to an eventual fifty per cent. Parity, in other words.

Initially, my colleagues’ response was that it was an interesting suggestion.

[

‘Interesting’ was another Civil Service form of abuse, like ‘novel’ or, worse still, ‘imaginative’ – Ed

.]

‘Interesting’ was another Civil Service form of abuse, like ‘novel’ or, worse still, ‘imaginative’ – Ed

.]

Arnold set the tone for the proper response. His view was that it is right and proper that men and women be treated fairly and equally. In principle we should all agree, he said, that such targets should be set and goals achieved.

Other books

Sanctuary Line by Jane Urquhart

La cultura popular en la Edad Media y el Renacimiento by Mijail Bajtin

Boiling Point by Diane Muldrow

American Visa by Juan de Recacoechea

False Bottom by Hazel Edwards

Escape Me Never by Sara Craven

Smoke Mountain by Erin Hunter

Microsoft Word - MeantForEachOther.doc by Allison

Steampunk Fairy Tales by Angela Castillo

A House Without Windows by Stevie Turner