The Complete Yes Minister (56 page)

When I got there I was told of a big Government administrative reorganisation. Not a reshuffle; I stay Minister of Administrative Affairs at the DAA. But I’ve been given a new remit: local government. It’s quite a challenge.

[

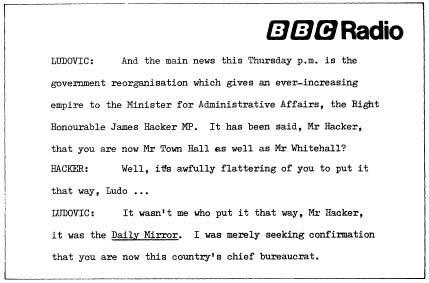

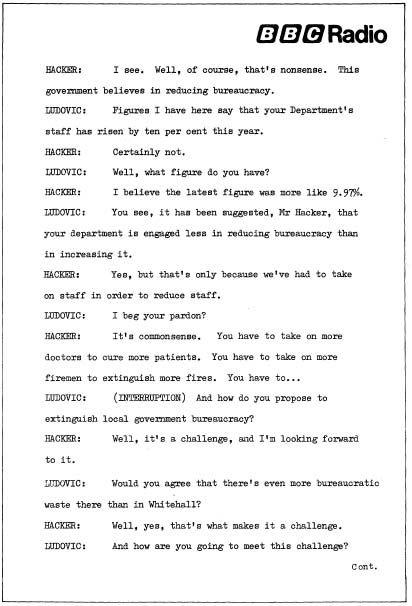

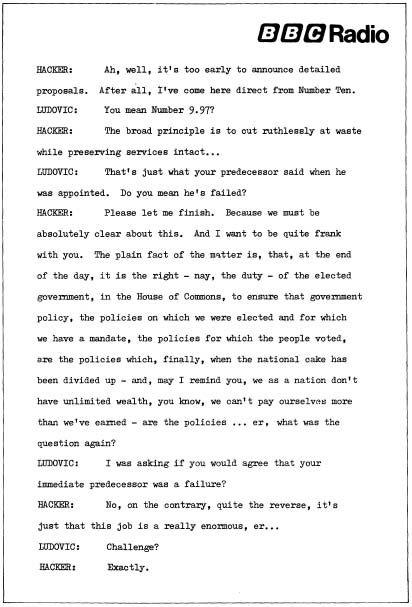

Later that day Hacker was interviewed by Ludovic Kennedy in

The World at One,

a popular radio current affairs programme in the 1970s and 80s

.

Later that day Hacker was interviewed by Ludovic Kennedy in

The World at One,

a popular radio current affairs programme in the 1970s and 80s

.

We have obtained a transcript of the broadcast discussion, which we reproduce below – Ed

.]

.]

[

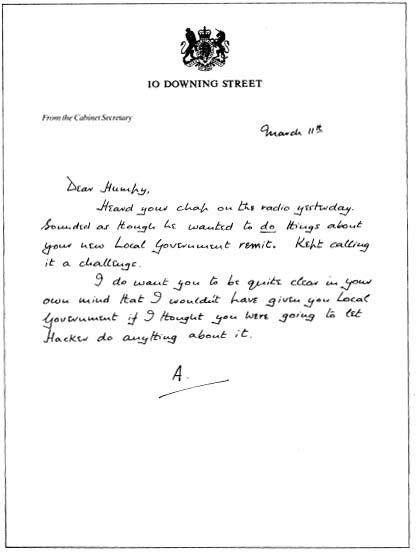

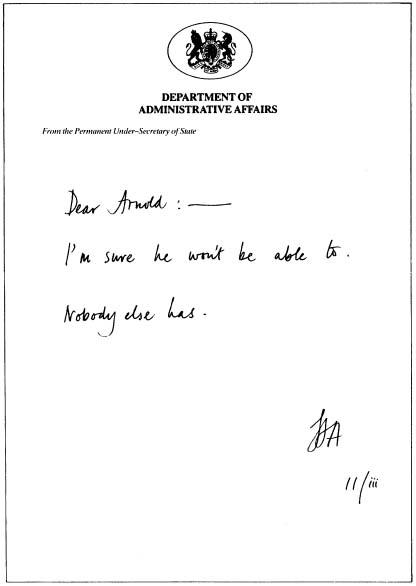

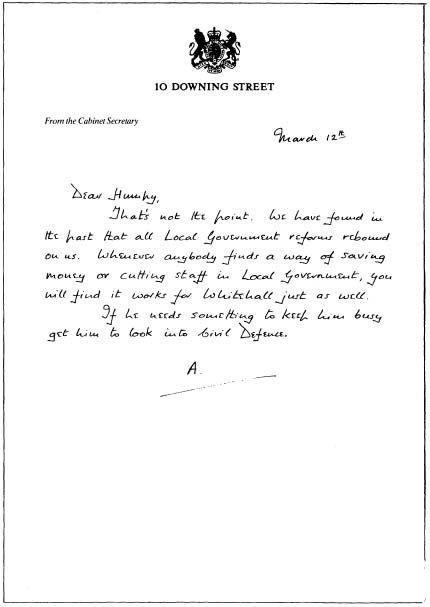

The following day Sir Humphrey Appleby received a note from Sir Arnold Robinson, Secretary of the Cabinet. We reproduce below the exchange of notes that ensued – Ed

.]

The following day Sir Humphrey Appleby received a note from Sir Arnold Robinson, Secretary of the Cabinet. We reproduce below the exchange of notes that ensued – Ed

.]

The reply from Sir Humphrey Appleby:

A reply from Sir Arnold Robinson:

[

On the same date, 12 March, Sir Humphrey made a reference to this exchange of notes in his diary – Ed

.]

On the same date, 12 March, Sir Humphrey made a reference to this exchange of notes in his diary – Ed

.]

Received a couple of notes from A.R. Clearly he’s worried that Hacker may overstep the mark. I’ve made it plain that I know my duty.

Nonetheless, A. made a superb suggestion: that I divert Hacker by getting him to look into Civil Defence. By which he means fall-out shelters.

This is a most amusing notion. Everybody knows that Civil Defence is not a serious issue, merely a desperate one. And it is thus best left to those whose incapacity can be relied upon: local authorities.

It is a hilarious thought that, since the highest duty of government is to protect its citizens, it has been decided to leave it to the Borough Councils.

[

Hacker’s diary continues – Ed

.]

Hacker’s diary continues – Ed

.]

March 15th

I met a very interesting new adviser today: Dr Richard Cartwright.

We were having a meeting of assorted officials, of which he was one. I noticed that we hadn’t even been properly introduced to each other, which I had presumed was some sort of oversight.

But, as the meeting was breaking up, this shambling figure of an elderly schoolboy placed himself directly in front of me and asked me in a soft Lancashire accent if he could have a brief word with me.

Naturally I agreed. Also, I was intrigued. He looked a bit different from most of my officials – a baggy tweed sports jacket, leather elbows, mousy hair brushed forward towards thick spectacles. He looked like a middle-aged ten-year-old. If I’d tried to guess his profession, I would have guessed prep school science master.

‘It’s about a proposal, worked out before we were transferred to this Department,’ he said in his comforting high-pitched voice.

‘And you are . . .?’ I asked. I still didn’t know who he was.

‘I am . . . what?’ he asked me.

I thought he was going to tell me what his job is. ‘Yes,’ I asked, ‘you are what?’

He seemed confused. ‘What?’

Now I was confused. ‘What?’

‘I’m Dr Cartwright.’

Bernard chose this moment to intervene. ‘But if I may put it another way . . . what

are

you?’

are

you?’

‘I’m C of E,’ said Dr Cartwright puzzled.

‘No,’ said Bernard patiently. ‘I think the Minister means, what function do you perform in this Department.’

‘Don’t you

know

?’ Dr Cartwright sounded slightly horrified.

know

?’ Dr Cartwright sounded slightly horrified.

‘Yes,

I

know,’ said Bernard, ‘but the Minister wants to know.’

I

know,’ said Bernard, ‘but the Minister wants to know.’

‘Ah,’ said Dr Cartwright. We’d got there at last. No one would believe that this is how busy people in the corridors of power communicate with each other.

‘I’m a professional economist,’ he explained. ‘Director of Local Administrative Statistics.’

‘So you were in charge of the Local Government Directorate until we took it over?’

He smiled at my question. ‘Dear me, no.’ He shook his head sadly, though apparently without bitterness. ‘No, I’m just Under-Secretary rank. Sir Gordon Reid was the Permanent Secretary. I fear that I will rise no higher.’

I asked why not.

He smiled. ‘Alas! I am an expert.’

[

It is interesting to note that the cult of the generalist had such a grip on Whitehall that experts accepted their role as second-class citizens with equanimity and without rancour – Ed

.]

It is interesting to note that the cult of the generalist had such a grip on Whitehall that experts accepted their role as second-class citizens with equanimity and without rancour – Ed

.]

‘An expert on what?’

‘The whole thing,’ he said modestly. Then he handed me a file.

I’m sitting here reading the file right now. It’s dynamite. It’s a scheme for controlling local authority expenditure. He proposes that every council official responsible for a new project would have to list the criteria for failure before he’s given the go-ahead.

I didn’t grasp the implication of this at first. But I’ve discussed it with Annie and she tells me it’s what’s called ‘the scientific method’. I’ve never really come across that, since my early training was in sociology and economics. But ‘the scientific method’ apparently means that you first establish a method of measuring the success or failure of an experiment. A proposal would have to say: ‘The scheme will be a failure if it takes longer than this’ or ‘costs more than that’ or ‘employs more staff than these’ or ‘fails to meet those pre-set performance standards’.

Fantastic. We’ll get going on this right away. The only thing is, I can’t understand why this hasn’t been done before.

March 16th

The first thing I did this morning was get Dr Cartwright on the phone, and ask him.

He didn’t know the answer. ‘I can’t understand it either. I put the idea up several times and it was always welcomed very warmly. But Sir Gordon always seemed to have something more urgent on when we were due to discuss it.’

I told him he’d come to the right place this time and rang off.

Then Bernard popped in. He was looking rather anxious. Obviously he’d been listening-in on his extension and taking notes. [

This was customary, and part of the Private Secretary’s official duties – Ed

.]

This was customary, and part of the Private Secretary’s official duties – Ed

.]

‘That’s marvellous, isn’t it Bernard?’ I asked.

There was a pointed silence.

‘You’ve read the report, have you? Cartwright’s report?’

‘Yes, Minister.’

‘Well, what do you think of it?’

‘Oh, it’s er, that is, er it’s very well presented, Minister.’

The message was clear.

‘Humphrey will be fascinated, don’t you think?’ I said mischievously.

Bernard cleared his throat. ‘Well, I’ve arranged a meeting with him about this for tomorrow. I’m sure he’ll give you his views.’

‘What are you saying, Bernard? Out with it.’

‘Yes, well, as I say,’ he waffled for a bit, ‘um . . . I think that he’ll think that it’s er, beautifully . . . typed.’

And then surprisingly he smiled from ear to ear.

March 17th

Today I had the meeting with Sir Humphrey. It was supposed to be about our new responsibilities in the area of local government. But I saw to it that it was about Cartwright’s scheme.

It began with the usual confusion between us.

‘Local authorities,’ I began. ‘What are we going to do about them?’

‘Well, there are three principal areas for action: budget, accommodation and staffing.’

I congratulated him for putting his finger right on it. ‘Well done, Humphrey. That’s where all the trouble is.’

He was nonplussed. ‘Trouble?’

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘with all those frightful councils. Budget, accommodation and staffing. They all go up and up and up.’

‘No, Minister.’ He had assumed his patronising tone again. ‘I’m afraid you misunderstand. I’m referring to this Department’s budget, accommodation and staffing. Obviously they must all be increased now that we have all those extra responsibilities.’

I was even

more

patronising in my response. ‘No Humphrey, I’m afraid

you

misunderstand.’ I told him that local government is a ghastly mess, and that I was asking what we were going to do to improve it, to make it more efficient and economical.

more

patronising in my response. ‘No Humphrey, I’m afraid

you

misunderstand.’ I told him that local government is a ghastly mess, and that I was asking what we were going to do to improve it, to make it more efficient and economical.

He didn’t answer my question. He hesitated momentarily, and then tried to divert me with flattery. ‘Minister, this new remit gives you more influence, more Cabinet seniority – but you do not have to let it give you any more work or worry. That would be foolishness.’

Other books

Animal Attraction by Paige Tyler

The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer by Jennifer Lynch

Fear and Loathing at Rolling Stone by Hunter S. Thompson

Whiskey Bottles and Brand-New Cars by Mark Ribowsky

Hitching Rides with Buddha: A Journey Across Japan by Ferguson, Will

Desired by Nicola Cornick

Götterdämmerung by Barry Reese

Love's Baggage by T. A. Chase

Sudden Legacy by Kristy Phillips

Tactics of Mistake by Gordon R. Dickson