The Crimean War (64 page)

Authors: Orlando Figes

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Europe, #Other, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Crimean War; 1853-1856

‘Poor Poland!’ remarked Stratford Canning to Lord Harrowby, one of Czartoryski’s supporters. ‘Her revival is a regular flying Dutchman. Never is – always to be.’

6

6

With all the major issues resolved beforehand, the Paris congress proceeded smoothly without any major arguments. Just three sessions were required to draft the settlement. There was plenty of spare time for a full range of social engagements – banquets, dinners, concerts, balls and receptions, and a special celebration to mark the birth of the Prince Imperial, Louis-Napoleon, the only child of Napeolon III and the Empress Eugénie – before the diplomats finally assembled for the formal signing of the peace treaty at one o’clock on Sunday, 30 March.

Announcements of the peace were made throughout Paris. Telegraphs worked overtime to spread the news across the world. At two o’clock, the ending of the war was signalled by a thunderous cannonade fired by the guns at Les Invalides. Cheering crowds assembled in the streets, restaurants and cafés did a roaring trade, and in the evening the Paris sky was lit by fireworks. The next day, there was a parade on the Champ de Mars. French troops passed by the Emperor and Prince Napoleon, senior French commanders and foreign dignitaries, watched by tens of thousands of Parisians. ‘There was an electrical tremor of excitement in the crowd,’ claimed the official history of the congress, published the next year, ‘and from the people there was a deafening cheer of national pride and enthusiasm that filled the Champ de Mars better than a thousand cannon could.’

7

Here was the glory and popular acclaim Napoleon had wanted when he went to war.

7

Here was the glory and popular acclaim Napoleon had wanted when he went to war.

News of the peace arrived in the Crimea the next day – as long as it took for the telegram to be relayed from Paris to Varna and communicated by the underwater cable to Balaklava. On 2 April the allied guns in the Crimea were fired for the final time – in salute to mark the end of the war.

Six months were given to the allies to evacuate their armed forces. The British used the port of Sevastopol, where they oversaw the destruction of the magnificent docks by a series of explosions, while the French destroyed Fort Nicholas. There were enormous quantities of war

matériel

to be counted, loaded onto ships and taken home: captured guns and cannon, munitions, scrap metal and food supplies, including vast amounts of booty from the Russians. It was a complicated logistical operation to allocate it all to the various departments of the ministries of war, and many things were left behind, sold off to the Russians, or, like the English wooden huts and barracks, donated to them on condition that they were used ‘for the inhabitants of the Crimea who had been made homeless by the war’ (the Russians accepted the English offer but kept the huts and barracks for the army). ‘It is an enormous endeavour to carry off, in just a few months, everything that was brought here over a period of two years,’ wrote Captain Herbé to his family on 28 April. ‘A large number of the horses and mules will have to be abandoned or sold off cheaply to the population of the Crimea, and I don’t count on ever seeing mine again.’ The animals were not the only means of transport to be sold off privately. The Balaklava railway was purchased by a company established by Sir Culling Eardly and Moses Montefiore, who wanted to use the equipment to build a new railroad between Jaffa and Jerusalem, a communication that would ‘civilize and develop the resources of a district now wild and disorderly’, according to Palmerston, who authorized the sale. It would serve the growing traffic of religious pilgrims to the Holy Lands. The Jaffa railway was never built and in the end the Balaklava line was sold to the Turks as scrap.

8

matériel

to be counted, loaded onto ships and taken home: captured guns and cannon, munitions, scrap metal and food supplies, including vast amounts of booty from the Russians. It was a complicated logistical operation to allocate it all to the various departments of the ministries of war, and many things were left behind, sold off to the Russians, or, like the English wooden huts and barracks, donated to them on condition that they were used ‘for the inhabitants of the Crimea who had been made homeless by the war’ (the Russians accepted the English offer but kept the huts and barracks for the army). ‘It is an enormous endeavour to carry off, in just a few months, everything that was brought here over a period of two years,’ wrote Captain Herbé to his family on 28 April. ‘A large number of the horses and mules will have to be abandoned or sold off cheaply to the population of the Crimea, and I don’t count on ever seeing mine again.’ The animals were not the only means of transport to be sold off privately. The Balaklava railway was purchased by a company established by Sir Culling Eardly and Moses Montefiore, who wanted to use the equipment to build a new railroad between Jaffa and Jerusalem, a communication that would ‘civilize and develop the resources of a district now wild and disorderly’, according to Palmerston, who authorized the sale. It would serve the growing traffic of religious pilgrims to the Holy Lands. The Jaffa railway was never built and in the end the Balaklava line was sold to the Turks as scrap.

8

Considering how long it took to ship all these supplies to the Crimea, the evacuation was completed speedily. By 12 July Codrington was ready to hand over possession of Balaklava to the Russians before departing with the final British troops on HMS

Algiers

. A stickler for military etiquette, the commander-in-chief was offended by the low rank and appearance of the Russian delegation sent to meet him and receive control of Balaklava:

Algiers

. A stickler for military etiquette, the commander-in-chief was offended by the low rank and appearance of the Russian delegation sent to meet him and receive control of Balaklava:

There were about 30 Cossacks of the Don mounted and about 50 infantry. But such a lot! I could not have conceived the Russians would have sent such a dirty specimen of their troops. Never were [there] such figures in grey coats – so badly armed too – disreputable looking – we were all surprised and amused. I hope they intended to insult us by such specimens: if so, it must have rather turned the tables if they heard the remarks. The Guard marched on board – the Russians posted their sentries – and the evacuation was completed.

9

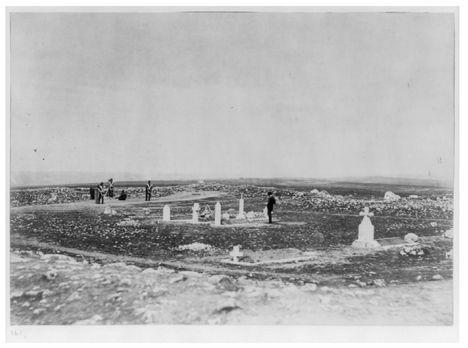

Left behind in the Crimea were the remains of many thousands of soldiers. During the last weeks before their departure, the allied troops laboured hard to build graveyards and erect memorials to those comrades they would leave behind. In one of his last reports from the Crimea, William Russell described the military cemeteries:

The Chersonese is covered with isolated graves, with longer burial grounds, and detached cemeteries from Balaklava to the verge of the roadstead of Sevastopol. Ravine and plain – hill and hollow – the road-side and secluded valley – for miles around, from the sea to the Chernaia, present those stark-white stones, singly or in groups, stuck upright in the arid soil, or just peering over the rank vegetation which springs from beneath them. The French have taken but little pains with their graves. One large cemetery has been formed with great care and good taste near the old Inkerman camp, but in general our allies have not enclosed their burial places … . The burial ground of the noncommissioned officers and men of the Brigade of Guards is enclosed by a substantial wall. It is entered by a handsome double gate, ingeniously constructed of wood, and iron hoops hammered out straight, and painted, which is hinged on two massive pillars of cut stone, with ornamental capitals, each surmounted by a cannon ball. There are six rows of graves, each row containing thirty or more bodies. Over each of these is either a tomb-stone or a mound, fenced in by rows of white stones, with the initials or sometimes the name of him who lies below, marked on the mound by means of pebbles. Facing the gate, and close to it stands a large stone cross … . There are but few monumental stones in this cemetery; one is a stone cross, with the inscription, ‘Sacred to the memory of Lieutenant A. Hill, 22nd Regiment, who died June 22, 1855. This stone was erected by his friends in the Crimea.’ Another is ‘In memory of Sergeant-Major Rennie, 93rd Highlanders. Erected by a friend.’ … [Another] is to ‘Quarter-master J. McDonald, 72nd Regiment, who died, on the 16th of September, from a wound received in the trenches before Sevastopol on the 8th of December, aged thirty-five years.’

10

The British cemetery at Cathcart’s Hill, 1855

After the allied armies left, the Russians, who had withdrawn towards Perekop during their evacuation, moved back to the southern towns and plains of the Crimea. The battlefields of the Crimean War returned to farms and grazing lands. Cattle roamed across the graveyards of the allied troops. Gradually, the Crimea recovered from the economic damage of the war. Sevastopol was rebuilt. Roads and bridges were repaired. But in other ways the peninsula was permanently changed.

Most dramatically, the Tatar population had largely disappeared. Small groups had begun to leave their farms at the start of the conflict, but their numbers grew towards the end of the war, in line with their fear of reprisals by the Russians after the departure of the allied troops. There had already been reprisals for the atrocities at Kerch, with mass arrests, confiscations of property, and summary executions of ‘suspicious’ Tatars by the Russian military. The inhabitants of the Baidar valley petitioned Codrington to help them leave the Crimea, fearing what would happen to them if their villages should fall into the hands of the Russians, ‘as our past experience of them gives us little ground to hope for good treatment’. Written and translated into English by a local Tatar scribe, their supplication continued:

In return for the kindness shown us by the English we should as soon cease to remember God as to forget Her Majesty Queen Victoria and General Codrington, for whom we will pray the five times a day that the Mahometan religion enjoins us to say our prayers, and our prayers to preserve them and the whole English nation shall be handed down to our children’s children.Signed in the names of the priests, nobles and inhabitants of the following twelve villages: Baidar, Sagtik, Kalendi, Skelia, Savatka, Baga, Urkusta, Uzunyu, Buyuk Luskomiya, Kiatu, Kutchuk Luskomiga, Varnutka.

11

Codrington did nothing to help the Tatars, even though they had provided the allies with foodstuffs, spies and transport services throughout the Crimean War. The idea of protecting the Tatars against Russian reprisals never crossed the minds of the allied diplomats, who might have included a stronger clause about their treatment in the peace treaty. Article V of the Paris Treaty obliged all warring nations to ‘give full pardon to those of their subjects who appeared guilty of actively participating in the military affairs of the enemy’ – a clause that appeared to protect not only the Crimean Tatars but the Bulgarians and Greeks of the Ottoman Empire, who had sided with the Russians during the Danubian campaigns. But Count Stroganov, the governor-general of New Russia, found a way around this clause by claiming that the Tatars had lost their treaty rights, if they had broken Russian law by departing from their place of residence without prior approval from the military authorities – as tens of thousands of them had been forced to do during the Crimean War. In other words, any Tatar who had left his home without a stamp in his passport was deemed to be a traitor by the Russian government, and was subject to penal exile in Siberia.

12

12

As the allied armies began their evacuation of the Crimea, the first large groups of Tatars also left. On 22 April, 4,500 Tatars set sail from Balaklava for Constantinople in the belief that the Turkish government had invited them to relocate in the Ottoman Empire. Alarmed by the mass exodus, which was a threat to the Crimean agricultural economy, Russian local officials looked for guidance from St Petersburg as to whether they should stop the departure of the Tatars. Having been informed that the Tatars had collaborated en masse with the enemy, the Tsar responded that nothing should be done to prevent their exodus, adding that in fact it ‘would be advantageous to rid the peninsula of this harmful population’ (a concept re-enacted by Stalin during the Second World War). Communicating Alexander’s statement to his officials, Stroganov interpreted it as a direct order for the expulsion of the Muslim population from the Crimea by claiming that the Tsar had said that it was ‘necessary’ (and not just ‘advantageous’) to make the Tatars leave. Various pressures were applied to encourage their departure: there were rumours of a planned mass deportation to the north, of Cossack raids on Tatar villages, of campaigns to force the Tatars to learn Russian in Crimean schools, or to convert to Christianity. Taxes were increased on Tatar farms, and Tatar villages were deprived of access to water, forcing them to sell their land to Russian landowners.

Between 1856 and 1863 about 150,000 Crimean Tatars and perhaps 50,000 Nogai Tatars (roughly two-thirds of the combined Tatar population of the Crimea and southern Russia) emigrated to the Ottoman Empire. Precise figures are hard to calculate, and some historians have put the figures much higher. Concerned about growing labour shortages in the region, in 1867 the Russian authorities tried to work out from police statistics how many Tatars had left the peninsula since the ending of the war. It was reported that 104,211 men and 88,149 women had left the Crimea. There were 784 deserted villages, and 457 abandoned mosques.

13

13

Along with the removal of the Tatar population, the Russian authorities pursued a policy of Christianizing the Crimea after 1856. More than ever, as a direct consequence of the Crimean War, they saw the peninsula as a religious borderland between Russia and the Muslim world over which they needed to consolidate their hold. Before the war, the relatively liberal governor-general, Prince Vorontsov, had opposed the spread of Christian institutions to the Crimea, on the grounds that it would ‘germinate among the [Tatar] natives unfounded dangerous thoughts about intentions of deflecting them from Islam and converting them to Orthodoxy’. But Vorontsov retired from his post in 1855, to be replaced by the aggressively Russian nationalist Stroganov, who actively supported the Christianizing goals of Innokenty, the Archbishop of the Kherson-Tauride diocese, within which the Crimea fell. Towards the end of the Crimean War, Innokenty’s sermons had been widely circlated to the Russian troops in the form of pamphlets and illustrated prints (

lubki

). Innokenty portrayed the conflict as a ‘holy war’ for the Crimea, the centre of the nation’s Orthodox identity, where Christianity had arrived in Russia. Highlighting the ancient heritage of the Greek Church in the peninsula, he depicted the Crimea as a ‘Russian Athos’, a sacred place in the ‘Holy Russian Empire’ connected by religion to the monastic centre of Orthodoxy on the peninsula of Mount Athos in north-eastern Greece. With Stroganov’s support, Innokenty oversaw the creation of a separate bishopric for the Crimea as well as the establishment of several new monasteries in the peninsula after the Crimean War.

14

lubki

). Innokenty portrayed the conflict as a ‘holy war’ for the Crimea, the centre of the nation’s Orthodox identity, where Christianity had arrived in Russia. Highlighting the ancient heritage of the Greek Church in the peninsula, he depicted the Crimea as a ‘Russian Athos’, a sacred place in the ‘Holy Russian Empire’ connected by religion to the monastic centre of Orthodoxy on the peninsula of Mount Athos in north-eastern Greece. With Stroganov’s support, Innokenty oversaw the creation of a separate bishopric for the Crimea as well as the establishment of several new monasteries in the peninsula after the Crimean War.

14

Other books

Bound in Blue by Annabel Joseph

His Sassy Girl (Desiring the Forbidden Book 2) by Michaels, Megan

La Rosa de Alejandría by Manuel Vázquez Montalban

Together Apart by Martin, Natalie K

Awakened (Book #5 of the Vampire Legends) by Knight, Emma

The Dead Walk The Earth (Book 3) by Duffy, Luke

The Real Chief - Liam Lynch by Meda Ryan

No Greater Love by Danielle Steel

Confieso que he vivido by Pablo Neruda

Dragon in Exile - eARC by Sharon Lee, Steve Miller