The Dance of Reality: A Psychomagical Autobiography (25 page)

Read The Dance of Reality: A Psychomagical Autobiography Online

Authors: Alejandro Jodorowsky

Tags: #Autobiography/Arts

Destruction and restoration of a piano.

All of these acts, these true delusions, were conceived and realized by persons considered normal in real life. The destructive energies that eat away at us from the inside when they are left stagnant can be released through channeled and transformative expression. Once the alchemy of the act is accomplished, the anguish is transmuted into euphoria.

The ephemeral panics were conducted without publicity, with the place and time given out at the last minute. On average about four hundred people would attend through this system of word of mouth. Thankfully, no articles about them were published in the newspapers. The government’s office of performances, headed by an infamous bureaucrat named Peredo, exerted an imbecilic form of censorship. In one theatrical work I was forced to hide a character’s belly button. In another, the actor Carlos Ancira wore a cape with two balls about the size of soccer balls hanging at the bottom; the troublesome civil servant considered them too suggestive of testicles and made us remove them. Thanks to the discrete and free nature of our ephemerals, we were able to express ourselves without any problem. The reaction was very different when I was invited to perform one on national television.

My work in the Teatro de Vanguardia had drawn the admiration of Juan López Moctezuma, a writer and journalist who was the host of a cultural television program. He had been given an hour of airtime without any commercials because an American TV series that attracted the majority of viewers was on at the same time on a different channel. Juan asked me to do whatever I wanted during those sixty minutes. I concentrated deeply, then knew precisely what ephemeral act I wanted to perform: what I had hated most, back in my dark days, was my sister’s piano. That instrument, smiling sarcastically with its black and white teeth, showed me that Raquel was my parents’ favorite child. Everything was for her, nothing for me. I decided to destroy a grand piano on camera. The explanation I gave to the public on this occasion was the following: “In Mexico, as in Spain, bullfighting is considered an art. The bullfighter uses a bull for performing his work of art. At the end of the fight, when he has expressed his creativity by means of the bull, he kills it. That is to say, he destroys his instrument. I want to do the same thing. I will put on a rock concert, then I will kill my piano.”

I found an old grand piano in the newspaper classifieds that was within my price range and had it sent directly to the studio where the cultural program was filmed. I also hired a group of young amateur rock musicians. When the broadcast began, after reciting my text I gave the order for the group to start playing, pulled a sledge hammer out of a suitcase and began to demolish the piano with great blows. I had to use all my energy, which was augmented by the rage that I had built up over so many years. Smashing a grand piano to pieces is not easy. I progressed slowly but incessantly in the demolition. The few spectators called their family and friends. The news spread like an uncontainable flood: a madman is smashing a grand piano with a hammer on channel 3! After half an hour, most Mexican viewers had switched from their favorite programs to see what this strange man was doing. The phone calls rose in quantity from one hundred to a thousand, two thousand, five thousand. Parents’ groups, the Lions Club, the minister of education, and many other notable entities protested. How dare this man destroy such a precious instrument before the eyes of so many poor children? (At that hour, the children were asleep.) Who had allowed this scandalous act of violence to be shown? (The American program being aired at the same time was a bloody war show.)

By the time I finished my work, lying amidst the rubble with a couple of pieces on top of me in the shape of a cross from which I extracted a few plaintive notes, the scandal had reached national proportions. The next day, all the newspapers mentioned the ephemeral. I had stripped Mexican art of its virginity in a brutal manner. I was admired for my audacity while also considered a cursed artist. Satisfied with the enormous notoriety I had achieved, I declared that on the next program Juan López Moctezuma would interview a cow to show that she knew more about architecture than university professors. The television station declared that this program would not take place, because “no cows are allowed in the studio.” I answered, “That is not true, many cows perform in the soap operas.” There was a fresh scandal in the press. The students of the School of Architecture offered me their department’s amphitheater in which to interview the cow. I arrived there, in front of an audience of two thousand students, along with my cow, which a veterinarian had previously injected with a tranquilizer. I presented the animal with its rear, which I compared to a Gothic cathedral, facing the public. The interview lasted two hours with the laughter growing and growing, until a group of burly employees arrived to tell me, and my bovine companion, to leave that honorable place and never return.

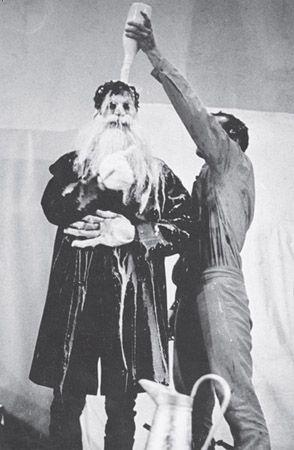

Ephemeral Panic

(Paris, 1974). Bathing the father (dressed as an enormous old rabbi) with a liter of milk before castrating him.

These ephemerals showed me the enormous impact that they could produce, much greater than conventional theater. In those formative years I believed that in order to change the collective mentality I had to attack the fossilized concepts of society; it did not occur to me that a sick person needs to be healed, not assaulted. I had not yet conceived of the social therapeutic act.

After returning to Paris I met with Arrabal and Topor, and for three years we attended meetings of the surrealist group. Breton, a few years before his death, old and tired, was already a supreme pontiff surrounded by untalented acolytes who were more concerned with politics than with art. It was then that we founded the panic group. We opened it with a four-hour ephemeral that I have described in another book. This show ended a stage in my life. In it, I was symbolically castrated, had my head shaved, was whipped, opened the belly of a huge rabbi from which I extracted pork offal, and was born through a huge vulva into a river of live turtles . . . I came out of it sick, exhausted, and anemic. Despite its success—

Plexus

magazine called it “the best happening Paris has seen,” and the beatnik poets Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Gregory Corso praised it and included it in their

City Lights Journal—

I was not satisfied. I saw the specter of dark destruction prowling about me and felt more than ever that theater must go in the direction of light. In search of positive action I abandoned all exhibitionist theatrical activity, with its desire for recognition, awards, reviews, and mention in the media, and began the practice of theatrical advising.

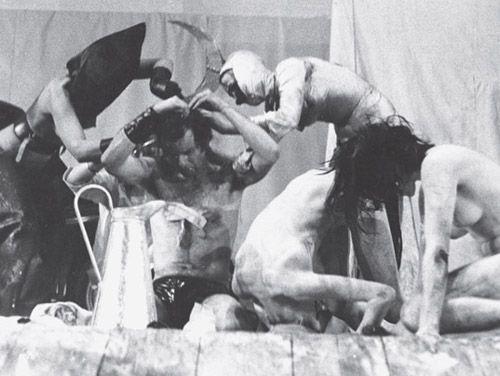

Ephemeral Panic

(Paris, 1974). The “ furies” use scissors to cut me a suit made of raw beef. The meat was later fried and served to the audience. Photo: Jacques Prayer.

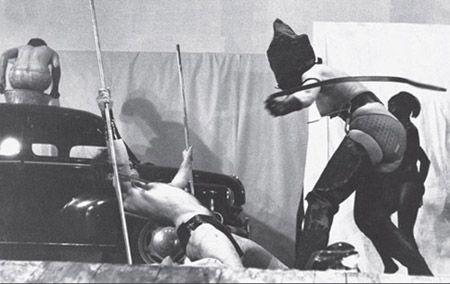

Ephemeral Panic

(Paris, 1974). One woman dressed as the moon and another dressed as an executioner shave my head on stage. There is a viper on my chest. Photo: Jacques Prayer.

Ephemeral Panic

(Paris, 1974). I submit to torture in order to rid myself of my physical narcissism. The executioner whips me until I bleed. Photo: Jacques Prayer.

If someone wanted to express his psychic residue, the serpents of shadow that gnaw at him from within, I would communicate the following theory to him: “The theater is a magical force, a personal and nontransmissible experience. It belongs to everyone. If you simply decide to act in a different way from how you act in everyday life, this force will transform your life. Now is the time to break away from conditioned reflexes, hypnotic cycles, and erroneous concepts of the self. The literature devotes a great deal of space to the theme of the ‘double,’ someone identical to you who gradually expels you from your own life, takes over your territory, your friendships, your family, your work, until you become an outcast, and even tries to kill you . . . I am here to tell you that in fact you are the ‘double’ and not the original. The identity that you think is your own, your ego, is no more than a pale imitation, an approximation of your essential being. If you identify with this double, as ridiculous as it is illusory, then your authentic self will suddenly appear. The master of the place will be restored to its rightful position. At that moment, your limited ‘I’ will feel persecuted, in danger of death, which indeed it is—because the authentic being appears by dissolving the double. Nothing belongs to you. Your only possibility of being is by appearing as the other, your profound nature, and eliminating yourself. This is a holy sacrifice in which you will give yourself entirely to the master, without fear. Since you live as a prisoner of your crazy ideas, your confused feelings, your artificial desires, and your useless needs, why not adopt a completely different point of view? For example, tomorrow you will be immortal. As an immortal, you get up and brush your teeth, as an immortal you get dressed and think, as an immortal you walk around the city . . . For a week, twenty-four hours a day, and with no spectator observing it other than yourself, be the man who will never die, acting as another person with your friends and acquaintances, without giving them any explanation. You will become an author-actor-spectator, presenting yourself not in a theater but in life.”

Although I devoted most of my time to filming, creating movies such as

Fando y Lis, El Topo, The Holy Mountain,

and

Santa Sangre

—an activity that gave me experiences that would require a whole book—I also continued developing the art of theatrical advice. I established a series of acts to perform in a given time: five hours, twelve hours, twenty-four . . . It was a program developed as a function of the problem brought in by the patient, aimed at breaking the character with which he had identified in order to help him restore ties with his profound nature. “Whoever is depressed, delusional, or failing, that is not you.” To an atheist, I assigned the task of taking on the personality of a saint for some weeks. To a woman who suffered from a hatred of her children, I assigned the duty—in a written contract, signed with a drop of her blood—of imitating motherly love for a hundred years. To a judge, concerned with the power he held to punish in the name of a law and a morality that he doubted, I assigned the task of dressing up as a vagrant to go begging in front of the terrace of a restaurant while taking handfuls of dolls’ eyes out of his pockets. To an unhealthily jealous man of questionable virility I assigned the task of showing up at a family reunion dressed as a woman.