The Dangerous Book of Heroes (10 page)

Read The Dangerous Book of Heroes Online

Authors: Conn Iggulden

One famous incident remains of John's ill-favored reign. He retreated north when he heard of the French threat, and on crossing the Wash, where Norfolk meets Lincolnshire, his baggage carts were caught by a rising tide and he lost the crown jewels as well as the money to pay his men. In 1216 he rode on to Newark without them and died probably from dysentery, alone, despised, and unmissed. He is buried in Worcester Cathedral. His oldest son went on to be King Henry III, and from him the Plantagenet, Tudor, and Stuart dynasties arose, including such famous monarchs as Edward I, Henry V, Henry VIII, and Elizabeth I.

Â

There are four copies of the Magna Carta still in existence, all in Latin. Two are in the British Library and the others in the cathedrals of Lincoln and Salisbury. The Great Charter was designed to protect the rights of nobles and commoners against the king. There were earlier charters, but this was the first to grant liberties to “all the free

men of our kingdom.” It also bore witness to the king being bound by the law, rather than above it. That is what is meant by the phrase “the rule of law”âthat all authority comes from the law itself.

From 1215 onward, rights existed in England that would travel to Ireland, Wales, Scotland, America, and much of the English-speaking world. The Magna Carta provided the foundation of Parliament and English law, which would influence the world through the British Empire. It was also the first step in creating an independent judiciary, as it allowed cases to be heard away from the king's presence. Those judges became the Common Bench, while the judges who followed the king were called the King's Bench. They too would eventually become separate from the royal court.

The original charter was confirmed more than fifty times by kings from Henry III to Henry V. Though it was largely overlooked between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries, it became prominent in the Puritan parliament after the civil war as a bulwark of democracy against dictatorship. As such, it was the basis of written law in the country and remained on the statute book until the nineteenth century, with some clauses surviving until the 1950s before being superseded by other laws. It is at least as important as the English Declaration of Rights of 1689, which allowed freedom of speech and was the condition by Parliament of the Prince of Orange taking the throne.

The ideals of the Magna Carta form the basis of legal systems around the world, from Australia and New Zealand to America, India, and Canada. In the U.S. Declaration of Independence and its Constitution, the words of Clause 39 appear twice in direct quotation. In Europe, the system of law has its origins in ancient Rome. One stark difference between the systems remains today. Under British law, that which is not forbidden is allowed. On the Continent, only that which is granted is allowed. It is a subtle but crucial distinction.

Clause 39, as quoted at the beginning of this chapter, created “habeas corpus”âliterally “thou shalt have the body”âwhich is fundamental to good governance. No man can be taken from his home and imprisoned without charge in Englandâuntil very recently,

with the introduction of anti-terror legislation. Although defeated in the British House of Lords, the notion that the House of Commons could vote to imprison a subject for forty-two days without charge is a step backward to John's times, when the monarch or nobles could take whatever they wanted and common men had no recourse to law.

Â

In recognition of England's common heritage with America, Queen Elizabeth II gave an acre at Runnymede to the United States on May 14, 1965. Apart from the American embassy, it is the only piece of U.S. soil in England. A memorial garden to John F. Kennedy is there, with views across the river to where King John sealed the Magna Carta. As Winston Churchill once said: “When the long tally is added, it will be seen that the British nation and the English-speaking world owe far more to the vices of John than to the labours of virtuous sovereigns.”

Recommended

History of England

by G. M. Trevelyan

Magna Carta and Its Influence in the World Today

by Sir Ivor Jennings

The Magna Charta Barons and Their American Descendants

by Charles Browning

O

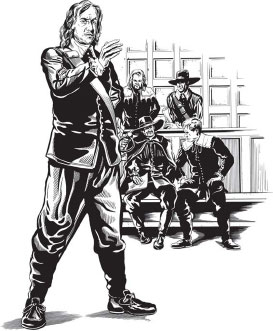

liver Cromwell remains one of the most controversial figures in historyâand indeed in this book. He is a hero to few, but it is no exaggeration to say that he changed his country forever and ushered in the modern age. Cometh the hour, cometh the man. He fought a civil war and executed a kingâand by doing so saved a nation from tyranny. He had no appreciable charm or desire to flatter, yet he could inspire intense loyalty. He was certainly a man of heroic imagination, able to encompass a future without slavish obedience to inherited nobility.

In Cromwell's time, kings such as James I and Charles I believed that they ruled by divine right, that they had been appointed by God. No royal decision could ever be questioned and no injustice challenged. The man who reversed this style of government was a fanatic both for Protestantism and for England. His life would make him the champion of the common man, and his efforts were the crucible out of which parliamentary democracy arose. As Churchill would say in 1947: “Democracy is the worst form of government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.”

Very little is known about Cromwell's first forty years. He was born in 1599, at the end of the Elizabethan age. Though the great storms of Elizabeth and Mary had passed, it remained an age of fervent religious belief, with Catholics and Protestants often in brutal conflict.

Cromwell went to Cambridge University in 1616 and left a year later when his father died. His mother was alone with seven unmarried daughters, and it is likely that Cromwell returned home to Cambridgeshire to protect them. He married Elizabeth Bourchier, from a wealthy Essex family, in 1620. The marriage seems to have been a happy one and produced nine children: five boys and four girls.

When James I died in 1625, his son ascended the throne as Charles I. From the first, Charles ruled as an autocrat, utterly disdaining the power of Parliament. He married a French Catholic and had obvious sympathies with Catholic countries such as Ireland and France. He created new taxes and made sweeping decisions on commercial policy. Lacking his father's intelligence and political sense, he simply could not see that the age had changed and men like Cromwell were on the rise.

In 1628, Cromwell stood for Parliament and in the same year was treated for

“valde melancholicus”

âdepression. His health was poor, and it was around this time that he experienced the conversion to Puritan Protestantism that would dominate his personal and political life. In a letter, he wrote: “If I may serve my God either by my doing or my suffering, I shall be most glad.”

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

Charles I resorted to “forced loans” from his subjects to support himself and imprisoned those who refused to pay. Puritans like Cromwell held up the king's lavish lifestyle as an example of everything they despised. In 1628, Cromwell took his seat in Parliament as they declared such taxation illegal. It was Parliament that voted the king's funds, so to maintain control, they attempted to make sure he could not find money anywhere else. The battle lines had been drawn.

In 1629, Charles dissolved Parliament and attempted to rule without them. Until he called them back to Westminster, they could not legally meet. He did not call them for eleven years. During that time he raised taxes directly from the population, which caused great resentment. Many Puritans left for America, to find new lives. The famous

Mayflower

had sailed in 1620, and there were many others in the years that followed.

In addition to Charles's English troubles, his attempt to reform the Scottish Church led to war. Desperate for money, the king could not raise funds on his own and was forced to return to Parliament, Cromwell among them. Instead of arranging the king's money, the MPs discussed the legality of his taxes. The “Short Parliament” lasted for only three weeks before Charles dissolved it in disgust.

By August 1640, the Scots had brought an army to Newcastle. Reluctantly, Charles was forced to recall Parliament once more. This is known as the “Long Parliament,” and once again Cromwell was present. They brokered the Treaty of London with the Scots in 1641, and one of Charles's problems ended. However, on that occasion the members of Parliament became determined to curtail the king's power over them, even if it meant civil war.

The mood of the country was with Parliament, in part because there was still a great fear of “popish” Catholic plots. Money and faith were the main issues that brought about the civil war.

In 1642, Charles wrote to Cambridge University for a loan that would have made him temporarily immune to parliamentary control. Cromwell himself went north on the orders of Parliament. With two hundred men, he blocked the road so that the silver could not be moved south, then took command of Cambridge Castle.

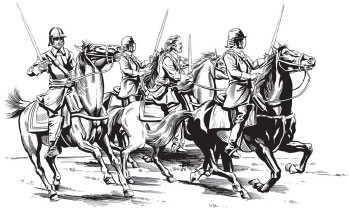

It was the last straw for the king, and in August he raised his banner in Nottingham. His loyal supporters, known as Royalists or Cavaliers, began to flock to him, while an army of Parliamentarians assembled under the Earl of Essex, Cromwell with them. They were commonly known as Roundheads, after the shape of their helmets.

The armies met first at Edgehill in October, a few miles from Banbury. In numbers they were roughly equal, and the battle ended in

stalemate. The king was unable to return to London and withdrew first to Reading and then to Oxford.

It is difficult now to imagine the shock wave that went through England at the outbreak of civil war. To attack the king himself was considered close to blasphemy in some quarters. Men like Cromwell had a sense of purpose, of right, of God-given destiny, that held the doubters together. He rose quickly in the ranks and in 1643 was effectively in sole command of forces in Essex, Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Huntingdonshire, Suffolk, and Norfolk.

His military ability has led some biographers to speculate that he must have been a soldier on the Continent for some of those mysterious early years. He was certainly a man who handled authority as if he had been born to it. As Cromwell wrote in a letter to subordinates: “Service must be done. Command you and be obeyed!” He regarded the battles as a test of Puritanism, but he was also a pragmatist. Famously, he warned his men: “Put your trust in God, but mind to keep your powder dry.”

The Royalists won a victory at Roundaway Down in 1643, while other battles ended in stalemate. No one could have predicted the outcome of the war as the year ended, but the most important battles were still to come.

Â

Cromwell was more than just a brave and quick-thinking military officer. He was also an able politician and, as the war went on, played a key role in parliamentary discussion. He proposed reform of the churches and the power of the bishops. He opposed the enclosure and sale of common land that was often the only means of support for the poorest families.

In February 1644, Cromwell was promoted to lieutenant general. Conscription was introduced around that time, in part to counter Highland Scottish forces coming south to support the king. The parliamentary force became known as “the New Model Army.”

On July 2, 1644, Cromwell commanded the left cavalry wing at Marston Moor, one of the most important battles of the English civil war. Parliamentary forces outnumbered the Royalists, and for the

first time a Royalist cavalry charge was broken in the field. The king's infantry was then slaughtered. Cromwell later denied his own part in it, giving the honor to God, who may or may not have been there. It was at Marston Moor that Prince Rupert, a grandson of James I, nicknamed Cromwell “Ironside” for his stern demeanor.

The battle of Naseby in 1645 was Cromwell's greatest military triumph. He commanded the cavalry at the town near Oxford and faced a roughly equal force of Royalist horse under Prince Rupert. King Charles I commanded a small reserve of infantry. Though the battle took place in June, the ground was sodden and soft in places, hampering maneuvers. As the forces came into range of each other, Cromwell saw that a line of trees and hedges provided perfect cover for a flank attack. He sent a message to his commanding officer asking him to withdraw, and, as he had hoped, the Royalist forces came forward in response. Cromwell sent a detachment of cavalry under cover of the hedges to pour musket fire into the Royalist flank. Like Marlborough and Wellington, he was a man able to read a battlefield and position his forces for maximum effect, remaining calm even under heavy fire.

The Royalist cavalry responded to the flanking attack with a sudden charge, routing some of the parliamentary forces against them and almost carrying the day. In one of those strange events that can decide battles and even the fate of nations, the pursuing Royalists came across the enemy baggage train and stopped to loot it. For a short time the Royalist infantry was left with just one cavalry wing. Nonetheless, they pushed the parliamentary forces back in brutal hand-to-hand fighting and with musket fire. From a hill, Cromwell watched coldly as men struggled and died in the mud. He held his own riders back, waiting for the remaining Royalist cavalry to charge. At the height of the battle, he saw them move.

He spurred his horse and the two forces galloped together in a great crash. The air filled with bitter musket smoke and the screams of the dying. It was a brief and bloody fight. The Royalists were quickly routed, and by the time Prince Rupert brought his cavalry back, the day had been lost.

Over the following year, Cromwell commanded at many different

sieges. In 1646 his army moved through Devon and Cornwall, rooting out the king's supporters. He accepted surrender whenever he could, more interested in winning quickly than in crushing the enemy. The first major conflict of the civil war ended in 1646.

Parliament was triumphant, the king had survived, and some regiments of the New Model Army were disbanded. For a time it looked as if Charles I might accept the limited power of a constitutional monarchy. He was held in various country houses in East Anglia and Hertfordshire and finally at Hampton Court. There Cromwell met the king and presented parliamentary bills that would severely limit the monarch's powers. Charles prevaricated and delayed, then escaped from custody in 1647, fleeing to the Isle of Wight.

The king still had many supporters in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and the south of England. In 1648 revolts against the New Model Army broke out and the Scots gathered an army of invasion to relieve Charles.

Once more, Cromwell joined his army. He took back Chepstow and Tenby, then starved Pembroke Castle in Wales into surrender. After that, he marched north against the Scottish army and defeated them at the battle of Preston, in Lancashire. Denied support, the king was taken into custody once more.

Parliament tried to open negotiations with Charles I. At first Cromwell supported the king abdicating in exchange for his life, but Charles

scorned the offer. He was then sent for trial in London. At an early session the king said: “I would know by what power I am called hither. I would know by what authority, I mean lawful authority.” He was found guilty of high treason, and Cromwell was one of those who signed his death warrant.

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

King Charles I was executed in London on January 30, 1649. When his head was cut off, the crowd was allowed to dip their handkerchiefs in royal blood as a souvenir. Cromwell looked down on the body and murmured: “Cruel necessity.”

England was without a king for the first time in more than a thousand years, and there were many who feared the void in power.

Cromwell's immediate purpose was to prevent the new regime from collapsing after the traumatic event. Ripples of shock spread through society, and there was even a threat of foreign invasion from Scotland, France, Ireland, or Spain. Not many in Parliament had thought beyond the death of the king. Mutinies occurred around England and had to be put down with force. The country was in danger of flaring up into a bloody revolution, and Parliament was hard-pressed to keep the peace.

In Ireland and Scotland, support was staunch for King Charles's eldest son, also named Charles. His father had been king of England, Scotland, and Ireland, and Royalists now supported the son's claim.

He was proclaimed king of Scotland after his father's death in 1649, though not crowned at Scone until 1651.