The Dangerous Book of Heroes (7 page)

Read The Dangerous Book of Heroes Online

Authors: Conn Iggulden

The next year Boone was shot in the ankle during a Shawnee attack on Boonesborough. For almost a year the settlement was under attack and the settlers' crops and cattle destroyed. In February 1778, Boone led out a party of thirty men for desperately needed fresh food and salt. While the others collected salt, Boone was hunting for game when he was sighted by some Shawnee. He ran, but he was now forty-five years old, and he was caught by fleet-footed warriors half his age.

The Shawnee chief, Blackfish, was about to fall on the rest of Boone's party and then assault Boonesborough. Boone persuaded Blackfish not to kill the salt collectors if they surrendered without fighting. They were all escorted to the Shawnee village of Chillicothe. Boone further persuaded Blackfish that Boonesborough was too heavily defended for an assault to succeed. The party was kept prisoner by the Shawnee for many months.

During his imprisonment, Boone was forced to “run the gauntlet”âto run between two lines of warriors facing inward and armed with

tomahawks and knives. He ducked, sidestepped, and twisted through the slashing tomahawks in the first half of the gauntlet, handed off the next few warriors, and simply sprinted past the last to survive. Blackfish adopted him into his tribe, giving him the name Sheltowee, “Big Turtle.” Yet he still turned him and his party over to the British at Fort Detroit as prisoners.

In mid-June, Boone discovered that the Shawnee were planning a major attack against Boonesborough. He escaped from Detroit and in five days made the 160-mile journey to the settlement by horse and foot to alert the settlers. The fortifications of the wooden village were quickly improved. In September, Shawnee surrounded Boonesborough, but Boone again delayed the assault by arranging a parley with Blackfish. During the negotiations in a meadow, fighting broke out. Boone and the settlers retreated inside, and the siege of Boonesborough began. It lasted ten days before the Shawnee withdrew, a siege not being their type of warfare.

Daniel Boone was charged by two officers of the patriot Kentucke militia of collaborating with the Loyalist Shawnee during his time with them. He was court-martialed in Boonesborough itself.

It is possible Boone collaborated with the Britishâalthough all his other actions belie it and there is no British record of itâbut almost certainly he was trying to stop needless bloodshed at Boonesborough. He was brought up with Native Americans, he liked them, and in their turn they admired him. A Shawnee victory over Boonesborough was not going to decide the outcome of the war.

Boone was acquitted and promoted to major, but he left to gather his family in North Carolina and never returned to Boonesborough. Instead, he established a new settlement, called Boone's Station, nearby. His court-martial had left a bitter taste, and he rarely spoke of it.

He joined General Clark's 1780 invasion of the Ohio country as its guide, taking part in the fighting at Pickaway (Piqua). In the division of the Kentucke territory that November, he was made lieutenant colonel in the Fayette militia and the following year was elected representative to the Virginia assembly. On his way to attend

the assembly, he was captured by British dragoons near Charlottesville. Assumed to be a civilian legislator, he was given parole after only a few days.

If Boone had been a Loyalist, he would by then have been known as a traitor to Britain. For he'd left Fort Detroit to warn Boonesborough of a Loyalist attack, campaigned with Clark, and fought at Pickaway. It's very unlikely he would have been released from Charlottesville.

In 1782 he fought the Shawnee in almost the last skirmish of the war, the battle of Blue Licks, where his son Israel was killed. He served once again as guide to Clark's second expedition into the Ohio country at the end of the year. By September 1783, when the United States of America was formally recognized as an independent nation, Daniel Boone was already a famous American.

The following year, at age fifty, he became a legend with the publication of

The Discovery, Settlement and Present State of Kentucke

by John Filson. This history includes a large appendix titled “The Adventures of Colonel Daniel Boone.” It sold successfully on both sides of the Atlantic, so that Boone became famous in the land of his father as well as his own. Filson interviewed Boone for the facts of his life but invented most of his speech. Filson, like later Hollywood portrayers of Boone, did not let truth stop him from embellishing a good story. He also omitted Boone's court-martial.

In 1785 a condensed version of Filson's account,

The Adventures of Colonel Boone,

was published. That, too, sold well. Through no desire of his own, Daniel Boone had become the world's archetypal frontiersman. He was the backwoodsman able to survive in the wilderness, living in harmony with nature and with the mutual respect of Native Americans.

After the Revolutionary War, Boone resettled his family at the river port of Limestone (Maysville) while he worked as a surveyor along the Ohio River. He bought a tavern, speculated unsuccessfully in land, and was again elected to the Virginia state assembly. In the northwest, though, war continued as Native American nations fought on until 1794 against U.S. expansion across the proclamation border.

Boone took part in one 1786 expedition, his last military action. After it he negotiated a Shawnee-American prisoner exchange.

He moved farther upriver to Point Pleasant in 1788, opened a trading post, and returned to hunting and trapping. After being appointed lieutenant colonel of the Kanawha militia, he was elected for a third time to the Virginia assembly in 1791. Still he couldn't settle, and he moved his large family back to son Daniel's land in Kentucke.

By then, his small wealth had disappeared, for he'd lost the colonial lands he'd cleared and claimed from lack of title in the new United States. In 1798 a warrant was issued for his arrest when he forgot, or ignored, a summons in a court case. Yet his fame had not died. The newly created state of Kentucky named Boone County for him the same year. Fittingly, the county contained a very large salt lake.

Copyright © 2009 by Matt Haley

However, it seems the new nation was not for him. Perhaps the continuing war against Native Americans, increasing federal interference in the states, new taxes, and escalating violence and riots persuaded him to move on. He was also in debt. In 1799 he left the United States.

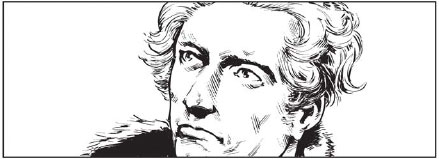

The silver-haired Daniel Boone led his family on an amazing journey, downriver along more than a thousand miles of the Ohio and the broad Mississippi all the way to Saint Louisâby canoe. He hunted and trapped along the riverbank while the family paddled

slowly downstream. In the afternoon they'd choose a site for their camp, light a fire, and prepare for the evening meal. It was idyllic. Legend says that on the wooden landing stage at Cincinnati somebody asked him why he was leaving. “I want more elbow room,” Boone replied laconically.

Louisiana was then a large Spanish colony, its borders spreading indeterminately north toward Canada. Within a year of his arrival in the Femme Osage district (Saint Charles County) of what is now Missouri, Boone was appointed syndic, a Spanish type of magistrate. He received land for his services and later was made military commandant of the district by the Spanish governor. He continued to hunt and trap for foodâa lot of families in the world did in those daysâand had one brief skirmish with the Osage tribe in the spring hunt of 1802. He discovered some Shawnee who had also escaped from Kentucky to Saint Louis, and they became friends.

In 1803 the U.S. government purchased Louisianaâalthough purchasing foreign territory contravened the new Constitution. However, under military threat from Napoléon Bonaparte in Europe, Spain had transferred her Louisiana colony to France and the transfer immediately rang loud alarm bells in Washington. The last thing English-speaking North America wanted was a return of French militarism.

President Jefferson wrote: “The day that France takes possession of New Orleans, we must marry ourselves to the British fleet and nation.” Bonaparte, despite his looting of various European nations, was short of currency with which to pay for his wars. For fifteen million dollars cash down he sold Louisianaâand Daniel Boone once again lived in the United States.

Almost immediately the new Louisiana Territory confiscated Boone's land, and he and Rebecca were forced to move to son Nathan's farm. After he petitioned Congress, his land was finally returned in 1814. He sold most of it to clear his outstanding Kentucky debts.

Rebecca, his wife of fifty-seven years, died in March 1813. She was buried near daughter Jemima's home on Tuque Creek. That

same year, the third account of Daniel Boone was published, a long poem by Rebecca's nephew Daniel Bryan. It was called

The Mountain Muse,

and Boone considered it embarrassingly inaccurate. He said: “Many heroic actions and chivalrous adventures are related of me which exist only in the regions of fancy.” It sold well, nevertheless.

Boone remained on his son's land and continued to hunt and trap into old age. It's probable he made one last, long hunt up the Missouri to the Yellowstone River around 1815, a remarkable journey for a man aged eighty-one. He died on September 26, 1820, and was buried beside Rebecca. Although the man was dead, the legend continued, and increased, with various colorful accounts over the years.

Strangest of all, Daniel Boone features in the classic poem

Don Juan

by Lord Byron. In the epic satire composed from 1819 to 1824, Byron wrote seven stanzas about “natural man” living simply in the wilderness:

Â

Of the great names which in our faces stare,

The General Boone, back-woodsman of Kentucky,

Was happiest amongst mortals anywhere;

For killing nothing but a bear or buck, he

Enjoyed the lonely, vigorous, harmless days

Of his old age in wilds of deepest maze.

Â

James Fenimore Cooper published the first Hawkeye tales in 1823, and a romantic account of Boone's life by Timothy Flint,

Biographical Memoir of Daniel Boone, the First Settler of Kentucky,

was released in 1833. Many more fiction and factual accounts followed, while Theodore Roosevelt founded the conservationist Boone and Crockett Club in 1887. A half-dollar coin was minted in 1934 to commemorate the bicentenary of his birth.

The remains of Daniel and Rebecca Boone were moved from Tuque Creek, Missouri, to Frankfort Cemetery, Kentucky, in 1845.

This has caused some resentment in Missouri, giving rise to another storyâthat the wrong bodies were removed, a mistake caused by the graves being left unmarked for some fifteen years. Daniel Boone's own words make a suitable comment: “With me the world has taken great liberties, and yet I have been but a common man.”

Recommended

The Discovery, Settlement and Present State of Kentucke

by John Filson

The Life and Legend of an American Pioneer

by John Faragher Daniel Boone Homestead, Reading, Pennsylvania

The Royal Air Force Fighter Command in the Battle of Britain

T

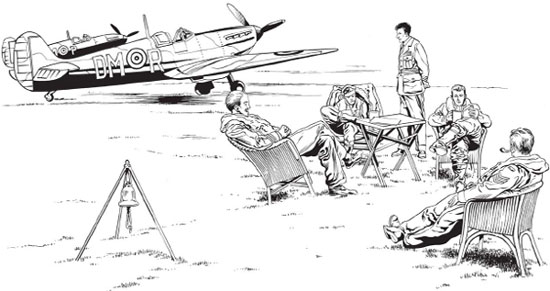

here were: 2,340 British, 32 Australians, 112 Canadians, 1 Jamaican, 127 New Zealanders, 3 Rhodesians, and 25 South Africans. In addition, there were 9 Americans, 28 Belgians, 89 Czechoslovakians, 13 French, 145 Polish, and 10 from the Republic of Ireland. They were the men and women of Royal Air Force Fighter Command, and they fought the most famous air battle of them allâthe battle of Britain.

Â

By the end of June 1940, the United Kingdom stood alone against Nazi Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, and France. The Czechs were conscripted into Nazi forces, while Vichy French forces fought with Germany until 1943 against Britain in the Middle East and North and West Africa. French spies around the world reported to Germany and Japan until they were captured, while in Southeast Asia the French agreed to Japan taking control of French Indochina (Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos).

From Norway to the Pyrenees, all of western and central Europe was Nazi-controlled, with enemy radio interception and spy networks operating in neutral Spain and Ireland. In the north, Sweden supplied the Nazis with steel and other metals. In the east, Russia, Hungary, Romania, and the Balkans supplied oil, coal, and food. In the south, Fascist Italy joined Germany and opened two more fronts against Britain in North and East Africa. At sea, German submarines

and surface raiders attacked unprotected British convoys, the escorts having been withdrawn to defend Britain against invasion.

The German victory in Europe had been so fast that no plans had been prepared for an invasion of Britain. In July that was remedied with Hitler's War Directive 16, which stated: “As England, in spite of her hopeless military situation, still shows no signs of willingness to come to terms, I have decided to prepare, and if necessary to carry out, a landing operation against her. The aim of this operation is to eliminate the English Motherland.”

For a German invasion to be possible, the Royal Navy had to be pushed out of the eastern English Channel, at least temporarily. To do that, Germany needed command of the air so that its formidable and experienced bomber and dive-bomber squadrons could knock out the navy. For command of the air, Royal Air Force Fighter Command first had to be destroyed.

To defeat Britain in 1940, German forces had only to take London, just fifty to sixty miles from the Kent and Sussex coasts. As with the Norman invasion of 1066, the remainder of the country could be overrun later. There would have been resistance, of course, far stiffer than they had encountered on the Continent, but an invasion was on. After all, the 1915 Gallipoli landings in the Mediterranean had been carried out successfully from ships' boats in the face of machine guns, artillery fire, and barbed-wire defenses, and without tanks. The Gallipoli campaign failed only because it was fought on a narrow peninsula and uphill against cliffs. No such problems would confront German troops on the broad and level battlefront of southeast England.

With German control of the air, there would have been no insurmountable problems for an invasion fleet to cross the channel, supported by glider troops and parachutists. The Royal

Navy stated that it could not prevent an invasion, because it wouldn't know the landing ports and beaches, but it would be able to stop support and supplies by sea to that invasionâas long as the RAF maintained control of the air.

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

The German Sixteenth and Ninth armies rehearsed for landings at ports and beaches between Folkestone and Brighton, while the Sixth Army practiced for landings between Weymouth and Lyme Regis. Panzer tanks were made watertight and fitted with snorkels, and rehearsed offloading some distance from a beach to proceed along the seabed and then ashore. The German navy scoured western Europe for suitable ships, barges, craft, and tugsâsome 2,500âand moved them to the ports of Holland, Belgium, and France. Meanwhile, under Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, the Luftwaffe prepared for “Eagle Attack.”

The amphibious invasion, known as Operation Sea Lion, was scheduled for the week of September 19â26, 1940, the date by which an invasion fleet could be assembled and when the tides were

favorable for a dawn landing on the Kent and Sussex beaches. Göring promised Hitler that by then Germany would command the air over the channel and southeast England. On August 1, Hitler signed War Directive 17 for the destruction of RAF Fighter Command, and so began the battle of Britain. It was to be a busy three months.

Â

RAF Fighter Command was then led by air chief marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, a brilliant, determined, but reserved man who knew more about aerial warfare than anyone else in Britain. It was Dowding who had changed the peacetime RAF from wooden biplanes to metal monoplanes. As a result, the first Hawker Hurricane flew in 1935 and the first Vickers Supermarine Spitfire in 1936. It was Dowding who arranged the first demonstration of Watson-Watt's new radar, who created the radar air-defense network, and who developed airborne radar for night fighters. In 1936 he was appointed commander-in-chief of the newly formed Fighter Command.

His senior officer was Air Commodore Keith Park, a New Zealand air ace who had twenty-four victories in World War I and who was the RAF's fighter expert. Together, they reorganized Fighter Command and the fighter defenses of Britain for war. An Observer Corps was formed of volunteers who reported from the ground all aircraft movements over Britain. Operation rooms were created for all levels of command, from airfields like RAF Duxford to Group Operations Headquarters at RAF Uxbridge. The airfields were converted to all-weather facilitiesâwith concrete runways as opposed to grass.

Dowding and Park also realized that, although the theorists correctly anticipated attack by large bomber squadrons, they were incorrect when they said there was no defense except attack by opposing bomber squadrons. There was a defense: fighter squadrons. Fortunately, they were supported in this belief by the new minister of defense, Sir Thomas Inskip. Dowding increased the number of fighter squadrons, airfields, and pilot-training units and created the vital centralized command linked to the new radar network. He pressed

and argued for even more pilots and ever more aircraft, although one type, the Defiant, turned out to be a turkey.

However, Dowding was not popular in the Air Ministry. He was usually right and ruffled too many feathers. He was “retired” in 1938 but immediately reinstated, a sequence that would happen four times. He sent a requisition to the Air Ministry for bulletproof glass for Hurricane and Spitfire cockpits; the politicians laughed at him. He told them: “If Chicago gangsters can have bulletproof glass in their cars, I can't see any reason why my pilots cannot have the same.” He got the glass. How out of touch many politicians were with the reality of modern warfare and the role of the RAF is difficult to appreciate many years later.

During the collapse of France, despite Dowding's advice, squadron after squadron of Hurricane fighters was deployed to France and destroyed. However, Dowding refused to commit Spitfire squadrons and, eventually, any more squadrons at all. Of 261 Hurricanes sent to France only 66 returned, a destruction rate of 75 percent. As a result, Fighter Command was reduced to almost half its strength, the loss of experienced pilots more critical than the loss of airplanes. If more squadrons had been sent to France, the battle of Britain would have been lost and Britain invaded.

Behind the scenes, Prime Minister Churchill appointed Canadian Lord Beaverbrook as minister of Aircraft Production, an inspired choice. Beaverbrook bypassed the Air Ministry, took over factories, and stopped production of bombers to increase production of Spitfire and Hurricane fighters. He had them delivered directly from the factories to the squadrons, created a “while-you-wait” repair service to which pilots flew their damaged fighters, and arranged the ferrying of aircraft across the Atlantic from Canada, which the Air Ministry had said was impossible. When the pro-Nazi American Henry Ford refused to support Britain by building Rolls-Royce Merlin engines under license, Beaverbrook paid the rival Packard company to do so. Later in the war, this led to the building of the brilliant British-designed and -engined P-51 Mustang fighter for the U.S. Army Air Force.

Dowding said later: “The country owes as much to Beaverbrook for the Battle of Britain as it does to me. Without his drive behind me I could not have carried on during the Battle.”

In the spring of 1940, Dowding appointed Keith Park as commander of 11 Group, the squadrons defending the vital southeast of England. Trafford Leigh-Mallory already commanded 12 Group, defending central England and Wales. Richard Saul commanded 13 Group, defending Scotland and northern England, while Quintin Brand commanded 10 Group, defending the west and southwest England.

So Dowding and a depleted Fighter Command entered the battle of Britain, facing a Luftwaffe that had flown and fought successfully in Spain, Poland, and western Europe. Göring's strategy was to bomb the fighter airfields out of action, destroy fighter aircraft on the ground by bombing and strafing, and destroy them in the air with his fighters. It was the same tactic used successfully against the Polish, Norwegian, French, Dutch, and Belgian air forces.

For the attack on Britain, the Luftwaffe had operational along the channel coast 656 single-seat single-engine Messerschmitt 109 fighters, 168 two-seat two-engine Messerschmitt 110 fighters, 248 two-seat single-engine Junkers Stuka dive-bombers, and 769 twin-engine bombers. Also on squadron strength but not operational were 153 Messerschmitt 109 fighters, 78 Messerschmitt 110 fighters, 68 dive-bombers, and 362 bombers.

In Denmark and Norway they had a further 34 Messerschmitt 110 fighters, 129 bombers to attack northern Britain, and 84 Messerschmitt 109 fighters (out of range of England but which could be brought south within range). In all, there were 2,749 aircraft. Additionally there were 244 reconnaissance and coastal aircraft for mine laying and pilot recovery.

On July 20, Fighter Command had operational 504 single-seat single-engine fighters, Hurricanes and Spitfires in a ratio of approximately four to one. Also on squadron strength but not operational were 78 Hurricanes or Spitfires for a total of 582 aircraft.

There were also 27 Boulton Paul two-seat single-engine Defiant fighters. The only time these were sent into action, July 19, they lost two-thirds of their number without a single loss to the enemy. They were not used again. The RAF also had Bomber Command and Coastal Command, but those aircraft could not be involved in the battle of Britain; they were not suitable.

In all aircraft, Fighter Command was outnumbered by four to one. In fighters, it was outnumbered by two to one.

Radar detection gave Fighter Command the time to deploy its squadrons to the right place at close to the right time, but rarely to the right height. The Nazi fighters invariably had the great advantage of height. Radar was vital to the battle, giving Fighter Command's fewer aircraft more time in the air, and to a certain extent redressing the imbalance of numbers, but this became a double-edged sword for the RAF pilots. It meant that they flew many more hours than the German pilots, an average of six sorties or more each day. In addition, Luftwaffe aircrew knew the time they were to fly every day, whereas RAF pilots were on standby to “scramble” from dawn to dusk (woken at about 3:30

A.M

., stood down at about 8:30

P.M

.). As a result, the British pilots eventually became exhausted, and exhausted pilots make fatal mistakes.

Fighter Command did have the advantage of fighting over home territory, so that most of the pilots who survived a destroyed aircraft were returned to their squadron, whereas most Luftwaffe pilots who survived became prisoners of war. However, in war-experienced pilots as well as reserve pilots, Fighter Command was vastly outnumbered by the Luftwaffe. It was this lack of pilots and experience that brought it closest to defeat.

In early July the Luftwaffe attacked shipping and convoys in the English Channel and North Sea, made fighter sweeps across Kent and Sussex, and probed and tempted Fighter Command in order to assess its response times and the standard of the opposition. Dowding was careful not to commit his men and airplanes at the beginning of the battle, so Park and Leigh-Mallory made only limited responses

to the attacks on shipping. The fighter sweeps were ignored. Even so, air activity was increasing. As early as July 10, Fighter Command flew more than six hundred sorties.

By the seventeenth, there were daylight bombing raids on factories in England and Scotland and on southern coastal towns, ports, and radar stations, as well as night bomber training flights. On the twenty-fifthâa rare sunny day in an overcast and wet Julyâseveral engagements took place protecting a convoy in the Dover Strait. Fighter Command lost 7 fighters against 16 German aircraft shot down, the heaviest casualties to that point. It was during that month that Park developed the tactic of sending Hurricanes to attack enemy bombers while Spitfires attacked the protecting fighters above. By the end of the month, however, neither air force was clear about how much damage had been done to the other.