The Danube (20 page)

Authors: Nick Thorpe

‘I had to have a hernia operation, but they wouldn't call a doctor. Another convict had to perform the operation on me, in atrocious conditions. But I survived it, because I was young. My father only lived another three years after his release. The older ones couldn't bear what they put them through. The humiliations, the heavy work, the poor food, everything. But we younger ones survived. If we had thought we would really have to serve twenty years there, it would have killed us. But we always believed that the democratic world would somehow stifle the appetite of Stalin and the others. But that's not the way it happened. The system only got better long after we were released.’

‘The mosquitoes were terrible. It is hard to imagine what we endured. At sunset millions of mosquitoes would descend on us, and start to attack. They bit into every bit of flesh that was not covered. Our faces, necks, arms, hands, feet, legs were all swollen with bites. But there was something which was even worse than the mosquitoes. The bedbugs. I was on the upper bunk, because I could climb easily. But we couldn't sleep in summer because of the bedbugs, sucking our blood. During the day the mosquitoes, during the night the bugs. Those were the weapons they used against us.’

‘Let me tell you about the work. We called it “Chinese style”. Because in China there are a lot of people. Our job was to build dykes. Some would build the walls, others would fill them in. And when there weren't dykes to build, we had to carry tree trunks four or five kilometres. Even a light tree gets heavy if you have to carry it a long way on your shoulders … We weren't allowed to fish, though there were a lot of fish there, and it was easy to catch them. There were many lakes and ponds on the islands. The trick was for one person to wade in, stir up the mud, so the fish had to come up for air, and then you grabbed them. But they searched us on our way back into the camp. If they found a fish on you, they put you in solitary. But sometimes people managed to smuggle them in … In winter there was no heating of any kind. We had our clothes and some blankets. You wrapped yourself up as best you could. And we survived it. We lived in barracks on Belene, fifty metres long. I don't know how we survived the cold. We survived the summer heat much better than the winter cold.’

Those serving the longest sentences were entitled to the least food and the fewest letters from their families. A single letter, censored by the camp authorities, and three kilos of provisions every three months. It was hard to get real information about the outside world or send information of their own. The only safe way was when someone was released. He would be asked to memorise hundreds of messages to relatives of the convicts stuck inside.

Todor Tsanev survived the long years on Belene, he says, with a lot of faith and a lot of hope. ‘If a person's spirit is broken, that's the end, he is annihilated. You have to believe in the good, and that the bad will finally be over one day. And we younger ones, we always asked for pig fat from home, and we toasted our bread in the morning, on an open fire, and spread pig fat on it, and that was when we talked, and encouraged each

other, saying that this will not last forever. And physically, the human body knows what to do. It knows its limits. We had to work, or we would have been killed like dogs, but we worked slowly, we tried to pace ourselves, not to get over-exhausted. You don't need anyone to tell you what to do, you don't need anyone to organise you. Your body knows. And all the time, even if you're not working, you act as if you are. If I hadn't known what to do, I wouldn't be here with you now. And I'm eighty years old! … I don't dream often about Belene any more, though I did for a long time after I was released. Nightmares. Nowadays only rarely, and they're not so bad as they were. For a time I had nightmares every night. Not any more … I try to stay healthy. I walk a lot. I don't have a car. I stay out of politics. I was very active in politics for a while, after 1990, but now I see that everything is lost. There's no way of putting the state back together. Those who say they can are just play-acting.’

He resents the luxury, the palaces of former communists, and those he calls ‘the mafia’. And he blames the communist leadership for what was done to him, and his country. ‘I don't blame those I knew who gave in to them, who capitulated. I blame those at the top, who ran the whole system. And since that system collapsed, they stayed on, to torture us in the new one!’ There's no true democracy in Bulgaria he concludes.

I drive slowly back up river, chastened by our meeting.

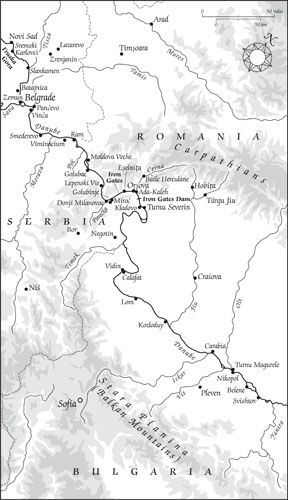

2. The Lower-Middle Danube, including the Iron Gates and the plains of Vojvodina.

CHAPTER

6

Gypsy River

Everyone likes to laugh at Roma monkeys … they add colour.

N

IKOLAI

K

IRILOV

1

The Western knights, with no enemy to fight, treated the whole operation in the spirit of a picnic, enjoying the women and the wines and the luxuries they had brought with them from home, gambling and engaging in debauchery, ceasing in contemptuous fashion to believe that the Turk could ever be a dangerous foe to them.

P

ATRICK

K

INROSS

2

T

HIRTY KILOMETRES

west of Ruse, the first poppies of spring grow beside the architect Kolyo Ficheto's bridge across the Yantra river, which flows down to the Danube from the Stara Planina mountains. To the north, the Danube is fed by the Olt and the Jiu rivers flowing down from the Carpathians. Barn swallows dart beneath the ten handsome stone arches of Ficheto's bridge, and the wavy, broken line built into the stone beneath the parapet gives a sense of movement, a nod towards the majesty of the river flowing beneath it. This was Kolyo Ficheto's trademark, imprinted on almost all the buildings he designed.

3

On the Danube shore in Svishtov, the roof of the Church of the Holy Trinity has the same wavy line, as though imitating the waves of the Danube or the Black Sea. The carved ends of the pews in the church at Balatonkenese in Hungary, the floor tiles of a friend's house in Mindszentkálla, have the same, quiet human tribute to the rhythms of nature.

The heart of the nineteenth-century Bulgarian writer Aleko Konstantinov is preserved in a jar in a museum named after him in Svishtov.

4

Next to it is the blood-stained jacket he was wearing when an assassin's bullet ended his life in 1897 at the age of only thirty-six. Konstantinov created the fictional character Bay Ganyo Balkanski, whose adventures were published in his 1895 best-seller

Bay Ganyo Goes to Europe

. Konstantinov won many enemies with his sarcastic portrayal of a provincial Bulgarian setting out to the West in peasant costume and returning home in elegant West European garb, having learnt the basics of capitalism during his sojourn among the peoples up the Danube, but none of their manners or restraint. ‘While Ganyo is simply a comic, primitive buffoon in the first part of the book that follows his exploits in Europe, he becomes the authentic and dangerous savage only on his return, among his own, where he is the nouveau riche and newly hatched corrupt politician,’ writes Maria Todorova.

5

Konstantinov thought up

Bay Ganyo

on a trip to Chicago for the World Fair in 1893, but the character is based on his own experiences in Bulgaria as a judge, before he quit in disgust at the political corruption of his profession. Konstantinov sought refuge from his life and times in humour, and joined a circle of artists known as ‘Merry Bulgaria’. He wrote under the ironic pseudonym ‘Shtastlivetsa’ – ‘The Happy One’. His family disowned him and he clashed frequently with the authorities, but the character he created lives on to haunt the imagination of Bulgarians finding their way in the European Union, not the ugly caricature of an outsider, mocking their worst characteristics, but of an insider. ‘Critics disagree on whether Bay Ganyo represents “Bulgarianness”. In his character, “national” features are combined with those of any upstart; thus he can also be interpreted as representative of human shamefulness,’ wrote Sonia Kanikova.

6

Konstantinov also wrote about the flaws of other societies. His description of his visit to America,

To Chicago and Back

, was published in 1894. According to Kanikova, ‘he regards the American way of life as anti-human and foresees some of the disastrous effects of technological progress and civilisation’. A soul brother, then, for Momi Kolev at the Koloseum Circus in Ruse.

Belene, the oversized village where Todor Tsanev suffered so long, presents a double-face to the world. A huge, unfinished nuclear power station lies along the low cliffs like a mortally wounded lion. An endless building site shelters behind a tall fence, decorated with coils of barbed

wire. A hundred security guards provide at least a little local labour. ‘Belene NPP – Energy for the Future’ proclaims an information board in the centre of the town. ‘Construction period – 59 months. Design lifetime – 60 years.’ The reality has proved a little harder. Begun in the 1970s, it was abandoned for lack of money in 1990, restarted and abandoned again several times. In January 2013, a referendum called by the opposition Socialist Party aimed at restarting Belene was approved by the public. But the governing party carefully changed the wording at the last minute into support for an unnamed nuclear reactor. Opponents argued that Belene would cost every Bulgarian dear, and that money in the European Union's poorest member state would be better spent on health care, pensions and safer energy.

Petar Dulev, the mayor of the municipality, is a firm believer in all things nuclear. ‘We always supported construction here. Despite the recent problems in Japan, we believe that nuclear power is the safest and cheapest source of energy, and will provide seven thousand jobs during the construction phase.’ ‘And the prison camp?’ I ask, cruelly. ‘The concentration camp is a black spot on the history of Belene. We try to build our prestige in other ways now. But perhaps in future it will attract tourists here, as a place of commemoration – like Alcatraz.’ As I leave, he presents me with a compact disc of Bulgarian folk songs by a group of local singers called ‘Danubian dawn’, backed by the musicians of Belenka and Dimum. The local paper,

Dunavski Novini

(Danube News), has a photo of the musicians on the back cover: two accordion players, a violinist and a drummer. The music alternates between the rousing and the melancholy, but is all rather fine. My favourite tracks are ‘Saint George, break in horse’, and ‘Why didn't you come yesterday night, elder brother Maria'ne?’

A high security prison has replaced one corner of the old, sprawling barracks of the prison camp, and the still undiscovered graves of those who died here. The rest of the island, and some twenty islands which surround it, have been turned into a national park. Out of the darkness of the past, something green and hopeful seems to be emerging.

Down on the shore, opposite Belene Island, is an elegant, modern building set on green lawns gently sloping down to the river. Here as much effort is going into preserving and restoring nature as once went into destroying it. The park is part of a World Bank and European Union effort to reduce the load of nutrient pollution in the Black Sea, most of

which arrives through the Danube, the Dniester and the Dnieper – the great flush toilets of Europe. Thanks to both the prison and the nature protection area, the twenty or so islands of the Belene archipelago are almost inaccessible to the public, a blessing for shy and rare birds like the white-tailed eagle and the pygmy cormorant that nest there. The park authority's job is to undo the damage caused by decades of forced labour by the inmates of the prison camp – the vast dykes that cut the Danube off from the wetland forests, built at such a cost in human misery, which deprived the fish of the spawning grounds they need and the birds of the fish they need to survive. If Todor Tsanev could see what is happening here, I think he would be glad. A system of sluices and waterways has been built on the island, to allow periodic, controlled flooding. After the first intervention, in 2008, monitors from the park recorded a surge in the number of birds. Whiskered terns, mistle thrushes, purple herons and mute swans appeared as if from nowhere. Floating watermoss, mouse garlic, yellow floating heart, fen ragwort and spring snowflake all flourished in the new conditions.

‘A big part of our work is to explain to local people, especially children, why restoring the wetlands is a good idea,’ said Stela Bozhinova, director of the Persina Nature Park.

7

‘Some people understand what we're doing, others resent the fact that we seem to be undoing their life's work, protecting the shoreline from flooding.’ The largest island, Persina, is fifteen kilometres long and six kilometres wide at its fattest point. The water is unusually low for May, which is disappointing for Stela and her team as it makes it harder to flood the forests for any useful length of time. A constant problem for the park is the functioning of the massive Iron Gates dam on the Romanian–Serb border. When water is released at the dam it creates a wave that travels down the river, still sixty to eighty centimetres high when it reaches Belene. That erodes the islands and damages the confluence of tributaries of the Danube such as the Yantra. Even so, the work to nurse the rarest species back from the brink of extinction is bearing fruit. Four of Bulgaria's fourteen white-tailed eagles nest on Persina Island – two adult pairs. This year one nest has two eggs in it, while they have not been able to get close enough to the other to count. If just two chicks survive from each nest, that would mean a nearly 30 per cent increase in Bulgaria's white-tailed eagle population.