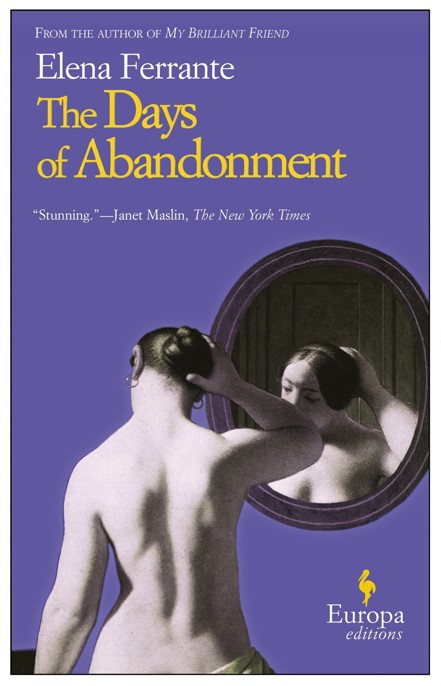

The Days of Abandonment

Europa Editions

116 East 16th Street

New York, N.Y. 10003

[email protected]

www.europaeditions.com

This book is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real locales are used fictitiously.

Copyright © 2002 by Edizioni E/O

Translation Copyright 2005 by Europa Editions

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

Cover Art by Emanuele Ragnisco

www.mekkanografici.com

ISBN 978-1-60945-029-8 (US & CA)

ISBN 978-1-60945-031-1 (World)

Elena Ferrante

THE DAYS OF ABANDONMENT

Translated from the Italian

by Ann Goldstein

O

ne April afternoon, right after lunch, my husband announced that he wanted to leave me. He did it while we were clearing the table; the children were quarreling as usual in the next room, the dog was dreaming, growling beside the radiator. He told me that he was confused, that he was having terrible moments of weariness, of dissatisfaction, perhaps of cowardice. He talked for a long time about our fifteen years of marriage, about the children, and admitted that he had nothing to reproach us with, neither them nor me. He was composed, as always, apart from an extravagant gesture of his right hand when he explained to me, with a childish frown, that soft voices, a sort of whispering, were urging him elsewhere. Then he assumed the blame for everything that was happening and closed the front door carefully behind him, leaving me turned to stone beside the sink.

I spent the night thinking, desolate in the big double bed. No matter how much I examined and reexamined the recent phases of our relationship, I could find no real signs of crisis. I knew him well, I was aware that he was a man of quiet feelings, the house and our family rituals were indispensable to him. We talked about everything, we still liked to hug and kiss each other, sometimes he was so funny he could make me laugh until I cried. It seemed to me impossible that he should truly want to leave. When I recalled that he hadn’t taken any of the things that were important to him, and had even neglected to say goodbye to the children, I felt certain that it wasn’t serious. He was going through one of those moments that you read about in books, when a character reacts in an unexpectedly extreme way to the normal discontents of living.

After all, it had happened before: the time and the details came to mind as I tossed and turned in the bed. Many years earlier, when we had been together for only six months, he had said, just after a kiss, that he would rather not see me anymore. I was in love with him: as I listened, my veins contracted, my skin froze. I was cold, he was gone, I stood at the stone parapet below Sant’Elmo looking at the faded city, the sea. But five days later he telephoned me in embarrassment, justified himself, said that there had come upon him a sudden absence of sense. The phrase made an impression on me, and I had turned it over and over in my mind.

Long afterward, he had used it again. It was about five years ago, and we were seeing a lot of a colleague of his at the Polytechnic, Gina, an intelligent, cultivated woman from a well-off family, who had been recently widowed and had a fifteen-year-old daughter. We had moved a few months earlier to Turin, and she had found us a beautiful house overlooking the river. On first impact, I didn’t like the city, it seemed to me metallic; but I soon discovered how pleasant it was to watch the seasons from the balcony of our house. In the autumn you could see the green of the Valentino grow yellow or red; the leaves, stripped by the wind, sped through the foggy air, and trailed over the gray surface of the Po. In the spring a fresh, sparkling breeze came from the river, animating the new shoots, the branches of the trees.

I had quickly adapted, especially since mother and daughter immediately did everything they could to alleviate any discomfort, helping me get to know the streets, taking me to the best shops. But these kindnesses had an ambiguous source. There was no doubt, in my mind, that Gina was in love with Mario; there was too much flirtatiousness, and sometimes I’d tease him outright, say to him: your fiancée called. He defended himself with a certain satisfaction, and we laughed about it together, but meanwhile our relations with the woman grew closer; not a day passed without her calling. Sometimes she asked him to go with her somewhere, or she would involve her daughter, Carla, who was having trouble with her chemistry assignment, or she was looking for a book that was no longer available.

On the other hand, Gina could behave with impartial generosity; she always had little gifts for me and the children, she loaned me her car, she often gave us the keys to her house near Cherasco, so we could go on the weekend. We accepted with pleasure; it was nice there, even if there was always the risk that mother and daughter would suddenly appear, turning our family routines upside down. But a favor has to be answered by another favor, and the courtesies became a chain that imprisoned us. Mario had gradually taken on the role of guardian for the girl; he went to speak to all her professors, as if standing in for the dead father, and although he was overburdened with work, at a certain point he had even felt obliged to give her chemistry lessons. What to do? For a while I tried to keep the widow at a distance, I liked less and less the way she took my husband’s arm or whispered in his ear, laughing. Then one day everything became clear to me. From the kitchen doorway I saw that little Carla, saying goodbye to Mario after one of those lessons, instead of kissing him on the cheek kissed him on the mouth. I immediately understood that it wasn’t the mother I had to worry about but the daughter. The girl, perhaps without even realizing it, and who knows for how long, had been assessing the power of her swaying body, her restless eyes, on my husband; and he looked at her as one looks from a gray area at a white wall struck by the sun.

We discussed it, but quietly. I hated raised voices, movements that were too brusque. My own family was full of noisy emotions, always on display, and I—especially during adolescence, even when I was sitting mutely, hands covering my ears, in a corner of our house in Naples, oppressed by the traffic of Via Salvator Rosa—I felt that I was inside a clamorous life and that everything might come apart because of a too piercing sentence, an ungentle movement of the body. So I had learned to speak little and in a thoughtful manner, never to hurry, not to run even for a bus, but rather to draw out as long as possible the time for reaction, filling it with puzzled looks, uncertain smiles. Work had further disciplined me. I had left the city with the intention of never returning, and had spent two years in the complaints department of an airline company, in Rome. After my marriage, I had quit and followed Mario through the world, wherever he was sent by his work as an engineer. New places, new life. And to keep under control the anxieties of change I had, finally, taught myself to wait patiently until every emotion imploded and could come out in a tone of calm, my voice held back in my throat so that I would not make a spectacle of myself.

That self-discipline turned out to be indispensable during our little marital crisis. We spent long sleepless nights confronting one another calmly and in low voices in order to keep the children from hearing, to keep from saying rash words that would open incurable wounds. Mario had been vague, like a patient who is unable to enumerate his symptoms precisely; I never managed to make him say what he felt, what he wanted, what I should expect for myself. Then one afternoon he came home from work with a look of fear, or maybe it wasn’t real fear, but only the reflection of the fear that he had read in my face. The fact is that he had opened his mouth to say something to me and then, in a fraction of a second, had decided to say something else. I realized it, I seemed almost to see how the words were transformed in his mouth, but I had quelled my curiosity to know what words he had renounced. It was enough to note that that painful period was over, that it had only been a momentary vertigo. An absence of sense, he explained, with unusual emphasis, repeating the expression he had used years before. It had possessed him, taking away the capacity to see and feel in the usual ways; but now it was over, the turmoil was gone. The next day, he stopped seeing both Gina and Carla, ended the chemistry lessons, returned to being the man he had always been.

These were the few irrelevant incidents of our sentimental journey, and that night I examined them in every detail. Then I got out of the bed, exasperated by a sleep that would not come, and made myself a cup of chamomile tea. Mario was like that, I said to myself: tranquil for years, without a single moment of confusion, and then suddenly thrown off by a nothing. Now, too, something had disturbed him, but I mustn’t worry, I just had to give him time to recover himself. I stood for a long time at the window that looked onto the dark park, trying to soothe my aching head against the cold of the glass. I roused myself only when I heard the sound of a car parking in the little square of our building. I looked down, it wasn’t my husband. I saw the man who lived on the fourth floor, a musician named Carrano, coming up the path, his head bowed, carrying over his shoulders the giant case of I don’t know what instrument. When he disappeared beneath the trees in the little square, I turned off the light and went back to bed. It was only a matter of days, then everything would return to normal.

A

week passed and my husband not only kept to his decision but reaffirmed it with a sort of merciless rationality.

At first, he came home once a day, always at the same time, around four in the afternoon. He was busy with the two children, chatting with Gianni, playing with Ilaria, and the three of them sometimes went out with Otto, our German shepherd, a dog as good as gold, taking him along the park paths to chase sticks and tennis balls.

I pretended to be occupied in the kitchen, but I waited anxiously for Mario to come and see me, to make his intentions clear, tell me if he had untangled the muddle he had discovered in his head. Sooner or later he arrived, but reluctantly, with an unease that each time became more visible, in opposition to which I presented, according to a strategy that I had devised during my sleepless nights, comfortable scenes of domestic life, understanding tones, an ostentatious sympathy, and even added some light remarks. Mario shook his head, I was too good, he said. I was moved, I embraced him, tried to kiss him. He withdrew. He had come—he was emphatic—only to talk to me; he wanted me to understand what sort of person I had lived with for fifteen years. So he recounted to me cruel memories of childhood, terrible problems of adolescence, nagging disorders of early youth. He wanted only to speak ill of himself, and no response I made to counter this mania for self-denigration could convince him, he wanted me at all costs to see him as he said he was: a good for nothing, incapable of true feelings, mediocre, adrift even in his profession.

I listened to him attentively, I contradicted him calmly, I didn’t ask him questions of any kind nor did I dictate ultimatums, I tried only to convince him that he could always count on me. But I have to admit that, behind that appearance, a wave of anguish and rage was growing that frightened me. One night I remembered a dark figure of my Neapolitan childhood, a large, energetic woman who lived in our building, behind Piazza Mazzini. When she went shopping, she always brought her three children along with her, through the crowded narrow streets. She would return loaded with vegetables, fruit, bread, the three children hanging on to her dress, to the overflowing bags, and she ruled them with a few light, foolish words. If she saw me playing on the stairway of the building, she stopped, put her load down on a step, rummaged in her pockets, and distributed candies to me, to my playmates, to her children. She looked and acted like a woman content with her labors, and she had a good smell, as of new fabric. She was married to a man from the Abruzzi, red-haired, green-eyed, who was a sales representative, and so traveled continuously between Naples and L’Aquila. Now all I remembered of him was that he sweated a lot, had a red face, as if from some skin disease, and sometimes played with the children on the balcony, making colored flags out of tissue paper, and stopping only when the woman called cheerfully: come and eat. Then something went wrong between them. After a lot of shouting that often woke me in the middle of the night, that seemed to be flaking the stone off the building and the street as if it had saw teeth—drawn-out cries and laments that reached the piazza, as far as the palm trees with their long, arching branches, their fronds vibrating in fear—the man left home for love of a woman in Pescara and no one saw him again. Every night, from that moment on, our neighbor wept. I in my bed could hear this noisy weeping, a kind of desperate sobbing that broke through the walls like a battering ram and frightened me. My mother talked about it with her workers, they cut, sewed, and talked, talked, sewed, and cut, while I played under the table with the pins and the chalk, repeating to myself what I heard, words between sorrow and warning, when you don’t know how to keep a man you lose everything, female stories of the end of love, what happens when, overflowing with love, you are no longer loved, are left with nothing. The woman lost everything, even her name (perhaps it was Emilia), for everyone she became the “

poverella

,” that poor woman, when we spoke of her that was what we called her. The

poverella

was crying, the

poverella

was screaming, the

poverella

was suffering, torn to pieces by the absence of the sweaty red-haired man, and his perfidious green eyes. She rubbed a damp handkerchief between her hands, she told everyone that her husband had abandoned her, had cancelled her out from memory and feeling, and she twisted the handkerchief with whitened knuckles, cursing the man who had fled from her like a gluttonous animal up over the hill of the Vomero. A grief so gaudy began to repel me. I was eight, but I was ashamed for her, she no longer took her children with her, she no longer had that good smell. Now she came down the stairs stiffly, her body withered. She lost the fullness of her bosom, of her hips, of her thighs, she lost her broad jovial face, her bright smile. She became transparent skin over bones, her eyes drowning in violet wells, her hands damp spider webs. Once my mother exclaimed:

poverella

, she’s as dry now as a salted anchovy. From then on I watched her every day, following her as she went out of the building without her shopping bag, her eye sockets eyeless, her gait shambling. I wanted to discover her new nature, of a gray-blue fish, grains of salt sparkling on her arms and legs.

Partly because of this memory, I continued to behave toward Mario with an affectionate thoughtfulness. But after a while I didn’t know anymore how to refute his exaggerated stories of childhood or adolescent neuroses and torments. In the course of ten days, as his visits to the children also began to decrease, I felt a sharp rancor growing in me, and eventually the suspicion arose that he was lying to me. I thought that as I was calculatedly demonstrating to him all my virtues of a woman in love and therefore ready to sustain him in his obscure crisis, so he was calculatedly trying to disgust me, to push me to say to him: get out, you make me sick, I can’t stand you anymore.

The suspicion soon became a certainty. He wanted to help me accept the necessity of our separation; he wanted it to be me who said to him: you’re right, it’s over. But not even then did I lose my composure. I continued to proceed with circumspection, as I always had before the accidents of life. The only external sign of my agitation was an inclination to disorder and a weakness in my fingers, and, the more the anguish increased, the harder they found it to close solidly around things.

For almost two weeks I didn’t ask him the question that had come immediately to the tip of my tongue. Only when I could no longer bear his lies did I decide to put his back to the wall. I prepared a sauce with meatballs that he really liked, I sliced potatoes to roast in the oven with rosemary. But I took no pleasure in cooking, I was indifferent, I cut myself with the can opener, a bottle of wine slipped out of my hand, glass and wine flew everywhere, even on the yellow walls. Right afterward, with a gesture too abrupt with which I intended to grab a rag, I also knocked over the sugar bowl. For a long fraction of a second the sound of sugar raining first on the marble kitchen countertop, then on the wine-stained floor exploded in my ears. It gave me such a sense of weariness that I left everything in a mess and went to sleep, forgetting about the children, about everything, although it was eleven o’clock in the morning. When I awoke, and my new situation as an abandoned wife returned slowly to my mind, I decided that I couldn’t take it anymore. I got up in a daze, put the kitchen in order, hurried to pick up the children from school, and waited for him to come by out of love for the children.

He came in the evening, he seemed in a good mood. After the usual greetings, he disappeared into Gianni and Ilaria’s room and stayed with them until they fell asleep. When he reappeared he wanted to slip away, but I forced him to have dinner with me, I held up before him the pot with the sauce I had prepared, the meatballs, the potatoes, and I covered the steaming macaroni with a generous layer of dark-red sauce. I wanted him to see in that plate of pasta everything that, by leaving, he would no longer be able to look at, or touch, or caress, listen to, smell: never again. But I couldn’t wait any longer. He hadn’t even begun to eat when I asked him:

“Are you in love with another woman?”

He smiled and then denied it without embarrassment, displaying a casual wonder at that inappropriate question. He didn’t persuade me. I knew him well, he did this only when he was lying, he was usually uneasy in the face of any sort of direct question. I repeated:

“It’s true, isn’t it? There’s another woman. Who is it, do I know her?”

Then, for the first time since the whole thing had begun, I raised my voice, I cried that I had a right to know, and I said to him:

“You can’t leave me here to hope, when in reality you’ve already decided everything.”

He, looking down, nervously gestured to me to lower my voice. Now he was visibly worried, maybe he didn’t want the children to wake up. I on the other hand heard in my head all the remonstrances that I had kept at bay, all the words that were already on the line beyond which you can no longer ask yourself what is proper to say and what is not.

“I will not lower my voice,” I hissed, “everybody should know what you’ve done to me.”

He stared at the plate, then looked me straight in the face and said:

“Yes, there’s another woman.”

Then with an incongruous gusto he skewered with his fork a heap of pasta and brought it to his mouth as if to silence himself, to not risk saying more than he had to. But he had finally uttered the essential, he had decided to say it, and now I felt in my breast a protracted pain that was stripping away every feeling. I realized this when I noticed that I had no reaction to what was happening to him.

He had begun to chew in his usual methodical way, but suddenly something cracked in his mouth. He stopped chewing, his fork fell on the plate, he groaned. Now he was spitting what was in his mouth into the palm of his hand, pasta and sauce and blood, it was really blood, red blood.

I looked blankly at his stained mouth, as one looks at a slide projection. Immediately, his eyes wide, he wiped off his hand with the napkin, stuck his fingers in his mouth, and pulled out of his palate a splinter of glass.

He stared at it in horror, then showed it to me, shrieking, beside himself, with a hatred I wouldn’t have thought him capable of:

“What’s this? Is this what you want to do to me? This?”

He jumped up, overturned the chair, picked it up, slammed it again and again on the floor as if he hoped to make it stick to the tiles definitively. He said that I was an unreasonable woman, incapable of understanding him. Never, ever had I truly understood him, and only his patience, or perhaps his inadequacy, had kept us together for so long. But he had had enough. He shouted that I frightened him, putting glass in his pasta, how could I, I was mad. He slammed the door as he left, without a thought for the sleeping children.