The Dirt (70 page)

Authors: Tommy Lee

Stay Centered

Strength

I’ll

never forget that bus ride from the courtroom, chained to the fucking seat, still in the suit I had been wearing in front of the judge only fifteen minutes before.

As they marched me into the jail, the first thing I heard was a loud cracking noise. I turned my head to see a little Latin dude lying on the floor of his cell with blood pouring out of his skull. I looked at the officers who were leading me to my cell and asked, “Isn’t anyone gonna help that guy?”

“Oh, that happens all the time,” they said nonchalantly. “He’s just having a seizure.”

I looked back at him and he was just lying there on the ground, not even moving. They brought me into a nearby room and undressed me. I stood there scared shitless and butt naked except for the rings in my nipples, my nose, and my eyebrow. An officer ran to get wire cutters. He clipped my nipple rings and my nose ring, but he couldn’t get my earrings off because they’re surgical steel. He begrudgingly let me keep them on. Then he handed me my jail gear: blue shirt, black shoes, and a bedroll with a towel, plastic comb, toothbrush, and toothpaste.

The officers led me back into the corridor and I noticed that, after half an hour, they were finally taking the Latino prisoner to the infirmary. It looked more like a fucking stroke than a seizure. As they led me past the other prisoners, I saw rows of gnarly motherfuckers, yelling shit like “Welcome, man” and “I’ll teach you how to treat a lady.” Half were excited, the other half wanted to kick my ass for fucking with a chick they probably whacked off to every night. The walk seemed like a mile, and I was so scared my knees buckled and the cops practically had to drag me. They threw me in an isolated cell and shut the heavy door, which sent a loud metallic thud reverberating through the cellblock. It was the loneliest fucking sound I’d ever heard.

This was the room I was supposed to spend the next six months in. It was basically a rock of concrete broken up only by a metal bed with a useless half-inch mattress. I had no one to talk to, nothing to write with, and dickshit to do. Whenever guards walked by, I would ask them for a pencil and they would ignore me. They were trying to let me know that I wouldn’t get any special treatment from them. The spoiled little brat in me was about to be taught a lesson. Because if he didn’t grow into a man in this place, he never would.

That evening, a big no-necked guard woke me up, banging on the door. “Get over here,” he barked.

I walked to the door, unsure whether I was about to receive a favor or a punishment. “What the fuck do you got earrings in for?” he asked.

“They left them there. They couldn’t get them out.”

“What are you, then, some kind of fucking faggot?”

I was prepared for the worst: a beating, a fucking, whatever. “Oh, dude, why are you hassling me?”

“No, I think you’re a faggot. And do you know what we do with faggots in here?”

I went back to my bed and ignored him. I didn’t know what to do. The fucker could have opened my cell door, clubbed me senseless, and in the morning no one would have cared.

After six or seven days of just sitting there going crazy with the knowledge that I had five months and three weeks of this shit left, a half-sized pencil came rolling under my door. A day later, a Bible materialized under the door. Then little religious pamphlets called “Our Daily Bread” started appearing every few days. I’d lie around with the Bible and pencil reading “Our Daily Bread,” and thanking whoever had given me these priceless gifts because I needed something to get my mind off the boredom and the torture. I must have replayed every moment of my relationship with Pamela in my head a thousand times.

I couldn’t understand why Pamela had followed through with pressing charges. She was probably scared and thought I was some crazy, violent monster, she probably thought she was doing the right thing for the kids, and she probably wanted an easy way out of a difficult situation. As much as I loved Pamela, she had a problem dealing with things. If something wasn’t right in her life, she’d rather get rid of it than take the time to work on it or fix it. She fired managers like I changed socks. Personal assistants and nannies would blow through our house like pages of a calendar: every day there was a new one, which always pissed me off because I wanted the kids to have someone consistent in their lives who they could trust and who would grow to love them almost as much as we did. So, the way I understood it, what Pamela did to me was basically fire me. I was fucking fired.

I needed to stop torturing myself and get some fucking good out of the experience, so I came to the conclusion that my mission was introspection. I needed to search inside myself and find the answers I was looking for. And the best way to do that was to stop finding faults with Pamela and other people and start finding the faults that lay within myself. At first, I just started writing on the walls. Most of what I wrote began with the word

why:

“Why am I here?” “Why am I unhappy?” “Why would I treat my wife like this?” “Why would I do this to my kids?” “Why don’t I have any spirituality?” “Why, why, why?”

After a few weeks, a guard asked me if I’d like to go up to the roof. “Dude, I would love that,” I told him. I could hardly remember what air smelled like, what the sky looked like, what the sun felt like on my face. I couldn’t wait to stand on this rad jail rooftop and take in the mountains and the city again.

They chained me, brought me to the roof, and my jaw dropped open, bro. The walls around the roof were so high that it was just like being in another cell. There were no trees, mountains, oceans, or buildings in sight. They stuck me in a cage up there called a K10, which is something the judge had ordered so that I’d be protected from the other inmates. It was about 4

P.M.

, and the sun was starting to sink out of view behind the wall. Its last beams were hitting the top corner of the cage. I pressed myself against the front of the cage and stood on my tiptoes so I could feel the sun on my face. As soon as its warmth spread over my forehead, nose, and cheeks, I burst into tears. I closed my eyes and cried as I bathed in the last ten minutes of sunlight left on that roof, the last ten minutes of sunlight I’d see for days, weeks, or months. Dude, I had taken the fucking sun for granted all my life. But, stick me in a dark, cold cell for a few weeks, and it was the greatest thing anyone could ever fucking give me. It felt like the most beautiful day of my life.

When I lost my little piece of sun, I pulled myself up on the dip bar they had in the cage and exercised. Before going to jail, when I was free on a fucking half-million-dollar bail, I had worked out for a month straight to prepare for the worst.

Outside the cage, the general population was playing in the yard—and I was a sitting target for all kinds of abuse. Huge gang-bangers would throw shit at me and yell, “You’re lucky you ain’t with us, you motherfucking pussy. Hitting girls. Shit, come out and play with the big boys.” It was humiliating, but I just kept my head down and my mouth shut, and thought about the sun.

As time passed, I began to have more contact with the outside world. No one was allowed to send books to the jail, because people would mail novels with pages dipped in acid and shit. But through my lawyer I was able to order three books every ten days on Amazon. I fucking needed mind food. I picked up books on the three things I most wanted to improve: relationships, parenting, and spirituality. I put Tai Chi diagrams up on my walls, learned about pressure points underneath my eyes that released stress, and became an expert on self-help books and Buddhism. I was determined to give myself a full-blown psychological, physical, and musical tune-up. I wanted to fix the problems that were holding me back: myself, my relationship with Pamela, and my restlessness in Mötley Crüe.

Though the judge had forbidden me to contact Pamela, there was nothing I wanted more than to speak to her and work things out. I was pissed at her, but I still felt trapped in a misunderstanding: a fucking missing stirfry pan had ruined my life. They eventually installed a pay phone in my cell, but it was a nightmare trying to reestablish contact with Pamela, who was still fuming over our fight. We began speaking through three-way conversations with our lawyers and therapists, but every time the conversation quickly degenerated into a mud-slinging fest and blame game. Eventually, a friend turned me on to an intermediary named Gerald, who was supposed to patch up all my relationships—with Pamela, with my children, and with the band.

I don’t know anything about Gerald’s credentials or training, but he had common sense. He told me that I had thrived on attention ever since I was a kid doing things like opening up my window so that the neighbors could hear me play guitar. In some sick sense, as much as I loved Pamela, she was also the guitar that I wanted to show all the neighbors I knew how to play. Only it turned out that I couldn’t play it that well. When the lights dim and the disco biscuits are gone and you’re sitting alone in a house with another person, only then does a relationship begin; and it will succeed if you can work through your problems and learn to enjoy the other person for who they really are without all the pats on the back and thumbs up from your bros. Perhaps that’s why celebrity relationships are so difficult: everyone puts you both on such a high pedestal that it almost seems like a disappointment when, at the end of the day, you discover that you’re just two human beings with the same emotional defects and mother-father issues as everybody else.

The other way Gerald helped me was by ordering children’s books for me through Amazon, then buying the same books for my boys. After I obtained permission from the court to talk to my kids, I would read them the stories over the phone while they looked at the pictures in the same book. It was important for me to keep that connection with my boys, because while I was in jail, Pamela was not only telling them that I was crazy but also trying to turn my own mother and sister against me. It was impossible for me to defend myself: not just from Pamela, but from the media, who were making me out to be a monster. What hurt me most, though, was not being home for Father’s Day and for Brandon’s birthday. That’s something a child doesn’t forget.

Every now and then, I would call home and Pamela would answer the phone. We would start talking, but within minutes the old hostility, oversensitivity, and accusations would rise to the surface and then suddenly—

bang!

—one of us would hang up on the other. End of communication.

I’d sit in my cell and cry for hours afterward. It was so frustrating not to be able to do anything about it. After a while, though, with my therapist on the phone as moderator, we learned to communicate again. I started responding to everything she said not with insecurity and defensiveness but with my own natural love, which was one good habit I had picked up as a child. I also learned that to be able to talk or even live with Pamela, I needed to stop testing her love for me, because when you test someone and don’t tell them, they’re bound to fail.

One Thursday, we were having a great conversation with my therapist and making a lot of progress when I heard all this loud talking and banging outside the cell. I stood up and yelled, “Man, can you guys keep it down!” But as those words came out of my mouth, I realized it wasn’t prisoners making the noise. It was that big no-neck motherfucker guard who had called me a faggot on my first night in jail. He stormed into my cell, grabbed the fucking phone cord, and ripped it out of the wall as I was talking. Then he filed a report to the sergeant stating that I had been mouthing off to him. They suspended my phone privileges for fourteen days. My lifeline to the outside world was fucking yanked, and I was in tears every day.

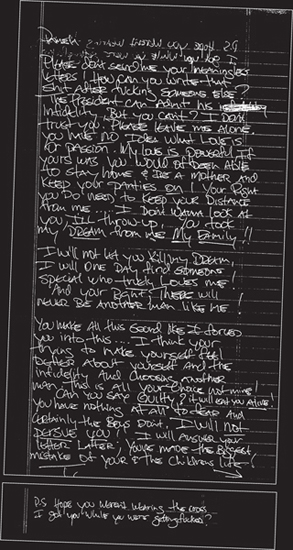

During those long-ass weeks, I worked on songs for what I decided would be a solo project, read parenting magazines and self-help books, and learned to write poetry, mostly about Pamela. She had started sending letters to me. And it was so frustrating, because she would have her assistant address and mail the letters for her. It made them seem impersonal, like I was just a chore her assistant could take care of. I tried so hard not to think like that, not to judge every little action as a sign of whether she loved me or not, because that was how I got into trouble in the first place.