The Eastern Front 1914-1917 (10 page)

Read The Eastern Front 1914-1917 Online

Authors: Norman Stone

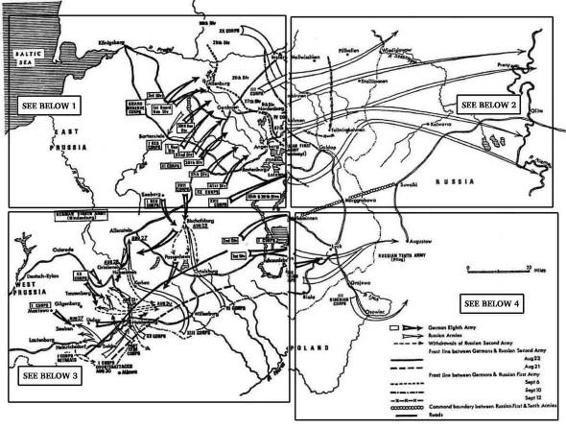

On the field, this superiority was whittled down. In the first place, the Russian commanders had little faith in their own second-line troops, whose divisions had more than two-thirds of their complement made up of reservists, not serving soldiers. The training of these reservists was thought to be too primitive for them to count as first-line soldiers, and the first-line elements in such divisions were alleged to be overwhelmed by the poor material surrounding them. I Army went to war with six and a half infantry divisions; but there were six more second-line divisions in its rear, disingenuously said ‘not to have taken part in initial operations’

18

—in other words, left kicking their heels in Grodno and Kovno. Similarly, the various fortresses of the area were thought to require large garrisons—Novogeorgievsk in particular—and the field army lost many men and guns in an unnecessary attempt to hold these various artillery-museums. All this was in strict contrast to German behaviour: the Germans used their second-line and even third-line troops to the full, and ruthlessly stripped their fortresses (Königsberg, Graudenz, Posen) of mobile guns. Of their thirteen divisions, only six were first-line and four second-line; the other three were a composite of four

Landwehr

brigades (made up of men in their late thirties and early forties) and two garrison,

Landsturm

brigades, containing in some cases men who had not been trained at all; moreover the seven non-first-line divisions were actually weaker in artillery than average Russian divisions, although, in the legendry of the time, this was not given prominence. The forces that actually reached the field in East Prussia were therefore less unevenly-matched than they might have been; and it is certainly true that, for the circumstances of East Prussia, the Russian army would have needed a more comfortable superiority. As things were, the German VIII Army contained thirteen infantry divisions, one cavalry division and 774 guns,

Tannenber.

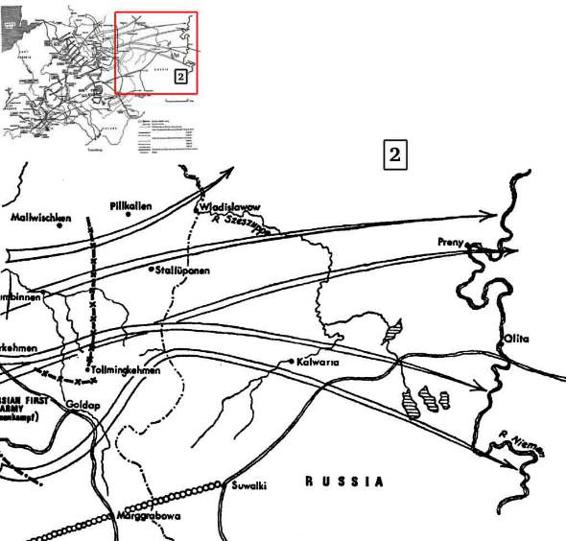

usually in batteries of six—in all, 158 battalions and seventy-eight cavalry squadrons. The Russian I Army had six and a half infantry and five and a half cavalry divisions, or 104 battalions and 124 squadrons, with 492 guns, usually in batteries of eight; the Russian II Army had fourteen and a half infantry and four cavalry divisions, or 304 battalions and III squadrons, with 1,160 guns. But, after an exercise in the non-bringing of troops to the decisive point that out-did the finest exploits of the Austro-Russians at Austerlitz, II Army was reduced to nine and a half infantry divisions, three cavalry divisions or 188 battalions, seventy-two squadrons and 738 guns; and it was this force that fought Tannenberg. The Tsarist army was not crippled by its inferiority in artillery or men; it was crippled by its inability to use its superiority.

The affairs of the north-western front were also bedevilled by an element of mistrust among senior officers that, in this first, confused, phase of the war mattered more than it did later. The leading personnel had been chosen from different cliques of the army—friends and enemies of Sukhomlinov, plebeian infantrymen on the one side, aristocratic cavalrymen on the other. Lord and peasant stared resentfully at each other across the staff-maps. As Grand Duke Nicholas’s

Stavka

came into existence, it could insist on key appointments, to cancel those made by the War Ministry. Zhilinski, commanding the front against Germany, was a Sukhomlinovite; but Rennenkampf, commanding I Army, was a notorious enemy. Samsonov, commanding II Army, was a Sukhomlinovite appointment, but their chiefs of staff, Mileant and Postovski, reversed the pattern—Rennenkampf communicated with Mileant only in writing throughout the East Prussian campaign, and refused to act on information given first to Mileant. For IX Army command in Warsaw, Sukhomlinov had named ‘the coarse Siberian’, Lechitski; Grand Duke Nicholas appointed as chief of staff one of his favourites, the ‘gentleman’, Guliewicz, an aristocratic Pole. The two men ended by addressing not a word to each other, after Lechitski refused permission for Madame Guliewicz to live in headquarters.

19

Communications, particularly between Zhilinski and Rennenkampf, were confused to the point where Zhilinski, nominally commander of the front, sometimes barely knew what was happening. The communications from I Army were so insultingly laconic and infrequent that Zhilinski, had to ask

Stavka

to intervene. Five messages were sent to Rennenkampf, and an adjutant of the Grand Duke himself—Kochubey—to remind him that he should let his seniors know what the army was doing.

20

In reality, the front command was almost as much of an illusion as was

Stavka

itself. The armies were merely allotted their forces and told to get on with their jobs. There was no real command-structure, merely a continual jostling between and within the great

command-groups, as men strove to defend their spheres of competence, or in Zhilinski’s case, incompetence.

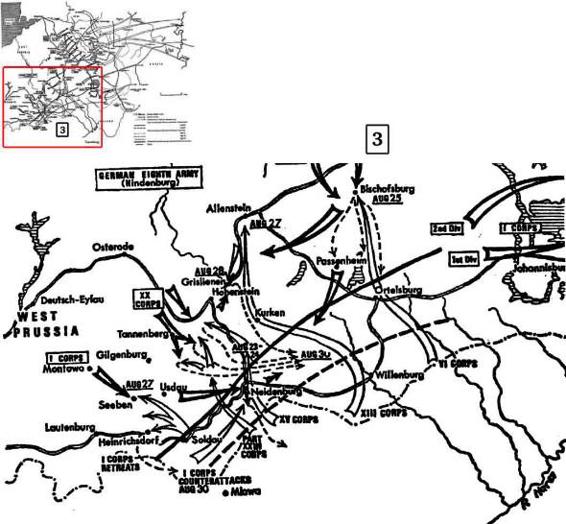

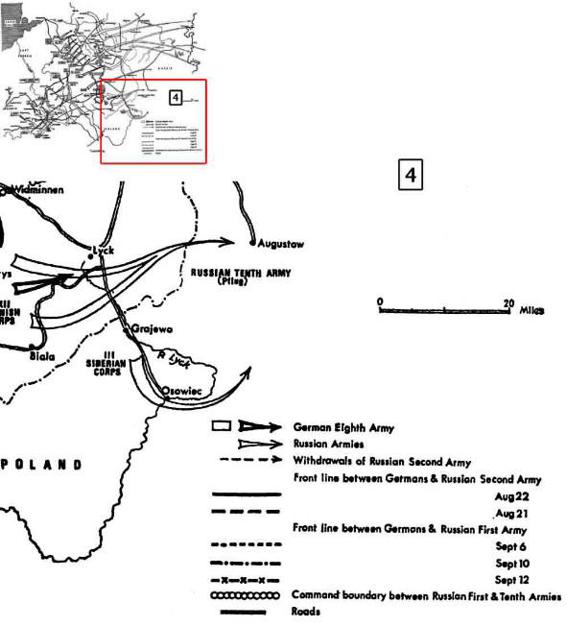

The Russian I Army was set to march west into East Prussia, while II Army came up from the south. In theory, this would catch the German defenders in a ‘pincer-movement’: the Germans’ flanks would be rolled up on either side of the

Angerapp-Stellung

, and they would be forced to retreat. This was a reasonable plan, but it depended on co-operation of the two armies involved. They would be separated by at least sixty miles as they encountered the main German positions, and an agile defence could attack first one, then the other. The Russian planners had been aware of this. But they chose inadequate methods of coping with the problem. They decided that the greatest danger would be an attack on the western flank of II Army—which could also affect the formation of the new IX Army near Warsaw. It was decided, therefore, to leave one corps of II Army virtually at a standstill, guarding this flank, and other troops—second-line divisions and cavalry—were given much the same task. In the same way, I Army worried about its open flank on the Baltic: maybe the Germans would organise a descent on the coast. A further group was detached as ‘Riga-Schaulen group’ to guard against this. Finally, to ensure that the inner flanks of I and II Armies kept together, one corps of II Army was kept between the two armies, and another pushed some way to the east, where it would be less effective. In this way, it was the Russians and not the Germans, who suffered from excessive concentration on their flanks. This reflected old-fashioned views of warfare. In earlier days, to have an enemy on the strategic flank was to risk all manner of tactical disadvantages—the enemy cavalry could cut communications with ease. Now, with cavalry so greatly reduced in serviceability, this danger was not so great. None the less, Zhilinski behaved as if the flanks were-all important. As a result, the attacking group of I Army was reduced to six and a half infantry divisions, that of II army to nine and a half; and the two groups would be at least six days’ march apart. Both were inferior to the German VIII Army, which would therefore have a chance to knock out first one, then the other. Tannenberg did not illustrate Russia’s economic backwardness. It merely proved that armies will lose battles if they are led badly enough.

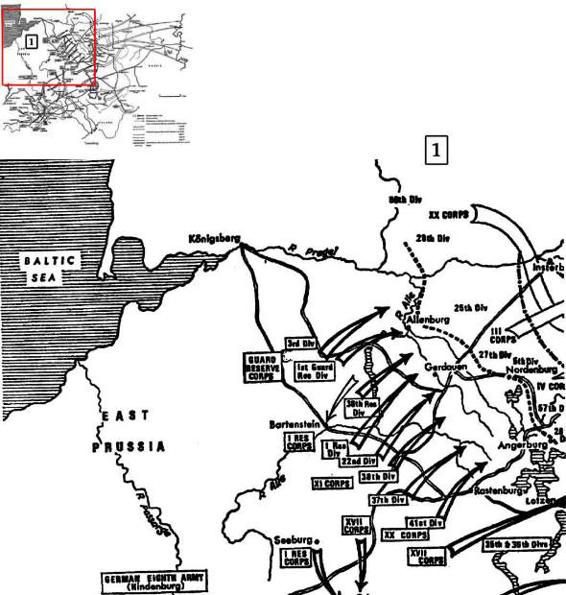

The German VIII Army more or less had its plan laid out for it. One of the Russian armies must be held by a weak screen, and the rest of the Germans’ forces sent against the other army. It was not clear, to begin with, which of the two armies must be attacked; it would depend on circumstances. There would be some advantage in attacking the Russian II Army from the west—here there were good railways. But the tactical circumstances decided against this plan. The Russian I Army crossed the

border on 15th August, from the east; II Army, struggling up from the south, reached the border only five days later, and did not make serious contact with German troops until 22nd August. Moreover, almost as soon as I Army crossed the border, it was engaged by German troops. The German VIII Army suffered from something of the same general problems as the Russians did. But it was much smaller than Zhilinski’s forces, more easily-controlled and supplied, and in the present case it had sense almost imposed on it by the nature of its task. Just the same, there was a problem with rebellious subordinates—in this case General von François, commander of 1. Corps, who arrogantly decided that he alone knew East Prussia, that the Russians could be defeated before they had even crossed the border. He engaged the Russians, to mutual bewilderment, in a set of flanking operations just after they came over the border. Both sides acquired a first experience of the deadly effect of enfilading gunnery; but nothing was decided. The German commander, Prittwitz, saw at least that large Russian forces were coming from the east, and he elected to attack these before those coming from the south could enter the battle. Tactically, he acquired a favourable position, since, as the Russians moved forward, they would have to divide their forces as they encountered the great heath of the river Rominte, and would perhaps leave their northern flank open.

Prittwitz let the Russian I Army advance, and attacked it on 20th August with nine divisions—half as much again as Rennenkampf deployed. He led off with a tactical success. The Russian northern group expected cavalry—of which there was a considerable quantity—at least to provide advance warning of any German movement. The cavalry failed to give this warning. In consequence, two German first-line divisions were able to march through woods, in the night of 19th–20th August, and fall on the unsuspecting Russian northern group—parts of which fled as far as Kovno, bearing regimental flags. François, commanding the German forces here, started off in pursuit, but then encountered a problem that came up subsequently, in greatly magnified form. Attackers might win a considerable tactical success; but they would be unable to follow it up, because cavalry was ineffective and supply-problems intervened. In this case, François’s two divisions were held up by the afternoon of 20th August, and François appealed to the rest of VIII Army to help him. But the German commanders to the south did not have the advantage of surprise that François had had. On the contrary, they had to launch expected, frontal attacks against an enemy that had begun to dig trenches of a sort. Mackensen, commanding the central corps of the army, lost 8,000 men in an hour or two, was then attacked in flank, and was rescued only with difficulty when the flanking Russian group was

itself taken in flank by a German division to the south. By the evening of 20th August, it was clear that Prittwitz’s attack had gone wrong; Gumbinnen was a clear Russian victory. Prittwitz panicked, for he knew that not only had he been beaten in the Gumbinnen battles, but also that there was a new Russian army approaching from the south. He might not even have time to retreat. He telephoned the German high command and told them that he must retreat as far as the lower Vistula, leaving East Prussia altogether; even the river could not be held, ‘it can be waded across everywhere’. All this was an exaggeration: the Germans had not been badly defeated, and could in any case recover quickly enough. The corps commanders themselves soon recovered their nerves as they noted Russian failure to pursue. Moltke, in the west, was struck by the indecision and panic of Prittwitz, and decided to have him removed. He selected as successor, Hindenburg, and chose as Hindenburg’s chief of staff one of the best technical experts of the German army, Ludendorff. These arrived to take command on 23rd August—Prittwitz learning of his dismissal, characteristically, only when his transport-chief reported that arrangements had been made for a special train carrying his successor.