The Egypt Code (18 page)

Authors: Robert Bauval

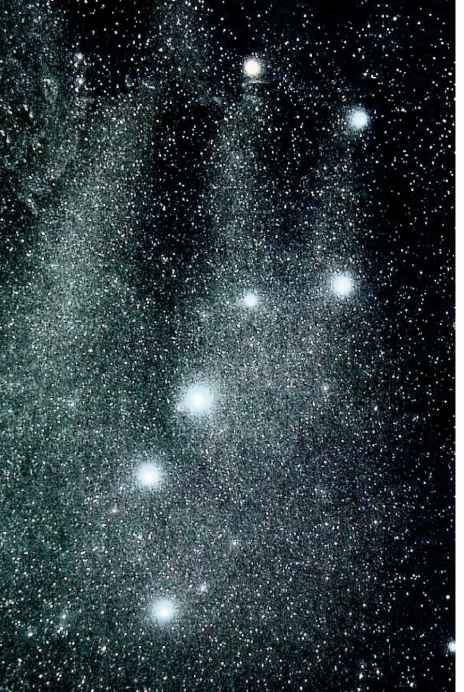

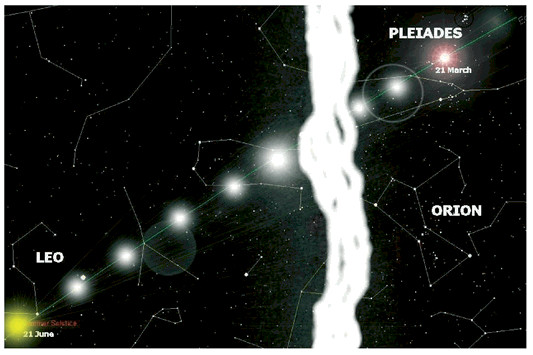

The sky-region of the Duat, showing Sirius (lower left of frame), the Pleiades (on middle right of frame), Orion (middle of frame) and the Milky Way.

(

Facing page

) The Big Dipper seen upright.

Facing page

) The Big Dipper seen upright.

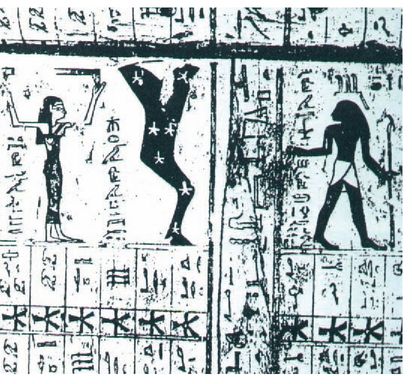

The

Bull’s Thigh

constellation of the ancient Egyptians (Big Dipper) on the lid of the Asyut coffin, 10th dynasty (c. 2050 BC).

Bull’s Thigh

constellation of the ancient Egyptians (Big Dipper) on the lid of the Asyut coffin, 10th dynasty (c. 2050 BC).

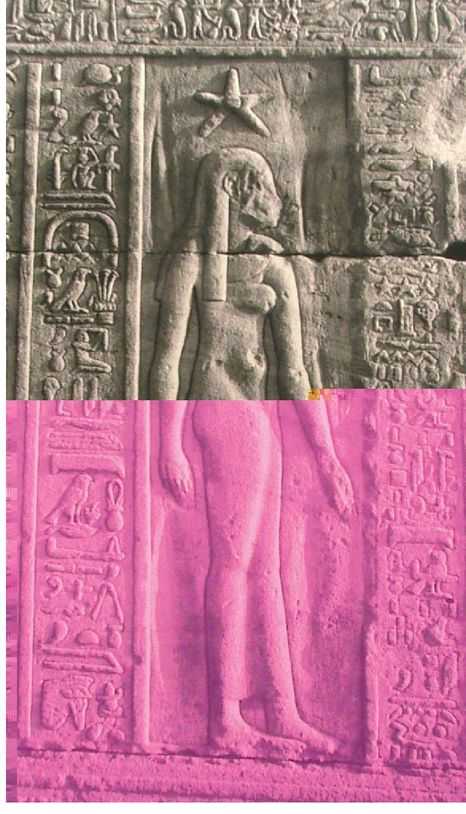

The goddess Isis with the Star Sothis (Sirius), Temple of Dendera (courtesy Sarite).

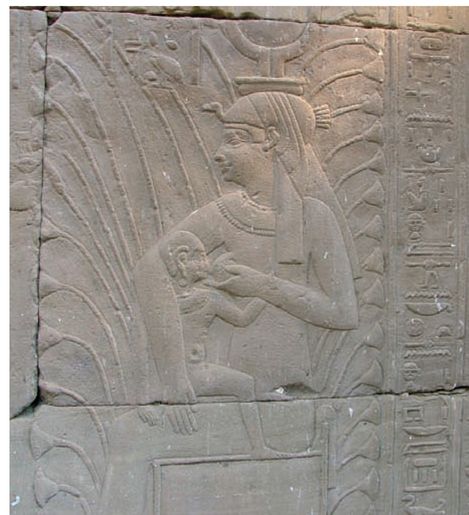

The goddess Isis suckling the infant Horus in the bullrushes, Temple of Horus at Edfu.

Sirius rising (lower left). Note Orion above the two persons.

The sun’s journey through the Duat: entry at the Pleiades (Spring Equinox) and exit at Leo (Summer Solstice).

Throughout history the lion has been the symbol of power, nobility and divine kingship. All one needs to do is stroll in any museum or art gallery to be confronted with this blatant fact. In cities such as Paris, London, Rome and Venice, lion symbols abound in squares and piazzas, guarding the entrances of villas and stately buildings, flanking fountains or emblazoned on the walls of churches and palaces. The leonine symbol is also found in heraldry, on coins and even on the old British passport. The archaeologist Selim Hassan gives us his own view of why lion symbolism was used especially in ancient Egypt:

In the earliest times the lion was the strongest and most imposing animal known to the Egyptians, and as such, it symbolised the king . . . the protector of his people; they looked to him to guard them from their enemies, to lead them into battle, to find them fresh hunting-grounds, and to feed them in time of famine. The king and the lion were one in their minds.

48

Another view is given by I.E.S. Edwards:

In Egyptian mythology the lion often figures as the guardian of sacred places. How or when this conception first arose is not known, but it probably dates back to remote antiquity. Like so many primitive beliefs it was incorporated by the priests of Heliopolis into the solar creed, the lion being considered the guardian of the Underworld (the Duat).

49

The lion in Egypt was, as everyone knows, more often than not depicted as a sphinx, that is to say a hybrid creature with the body of a lion and the head of a man or a woman, a ram or even a falcon. The latter, in fact, was very popular in statuary and religious art, and is known as a hierocosphinx (‘falcon-sphinx’ in Greek). It can be seen on a relief from the pyramid complex of Sahura at Abusir and, more particularly, at the temple at Edfu which was the principal sanctuary of the solar falcon-god Horus.

50

According to archaeologist Paul Jordan, the ‘earliest hybridisation of the lion known from archaeological records involves not a human head but the head and wings of a falcon (and) it may well be that the sphinx idea arose in the first (sic) as a lion-bodied transformation of Horus’.

51

There is an inscription also at the temple at Edfu which seems to confirm this alchemical merger of the falcon and lion in the person of the god Horus: ‘Horus of Edfu transformed himself into a lion which has the face of a man.’

52

50

According to archaeologist Paul Jordan, the ‘earliest hybridisation of the lion known from archaeological records involves not a human head but the head and wings of a falcon (and) it may well be that the sphinx idea arose in the first (sic) as a lion-bodied transformation of Horus’.

51

There is an inscription also at the temple at Edfu which seems to confirm this alchemical merger of the falcon and lion in the person of the god Horus: ‘Horus of Edfu transformed himself into a lion which has the face of a man.’

52

Sphinxes abound in Egypt, but the most famous of all is, of course, the Great Sphinx of Giza. Who or what did this universally known statue represent? Half-lion, half-man, is it a strange god whose name we have forgotten? Going by the inscriptions and reliefs from Edfu, one would be forgiven for thinking that the Great Sphinx represents Horus. But such obvious cerebral deduction is not how the minds of Egyptologists work when it comes to the identity of the Great Sphinx. Indeed, this is probably the most debated issue in Egyptology. The reason is complex, but its central core revolves around the adamant belief that there are no inscriptions contemporary with the Great Sphinx that speak of it let alone tell us who or what it represented. As the versatile Selim Hassan, who worked at the Sphinx for many years, was at a loss to explain: ‘this, in itself, is an enigma’.

53

On the other hand, because the Sphinx is located in front of Khafra’s pyramid, many Egyptologists are convinced that it represents Khafra, though this conclusion is not without its dissenters. Eminent Egyptologists such as Rainer Stadelmann and Vassil Dobrev, for example, are equally convinced that the Sphinx is not Khafra but Khufu. There are also others who, in their desire to remain neutral in this debate, are happy to see the Sphinx as representing no one in particular but as a symbol of the sun-god. Mark Lehner, for instance, writes, ‘The lion was a solar symbol in more than one ancient Near Eastern culture. It is also a common archetype of royalty. The royal human head on a lion’s body symbolises power and might controlled by the intelligence of the pharaoh, guarantor of cosmic order, Maat.’

54

53

On the other hand, because the Sphinx is located in front of Khafra’s pyramid, many Egyptologists are convinced that it represents Khafra, though this conclusion is not without its dissenters. Eminent Egyptologists such as Rainer Stadelmann and Vassil Dobrev, for example, are equally convinced that the Sphinx is not Khafra but Khufu. There are also others who, in their desire to remain neutral in this debate, are happy to see the Sphinx as representing no one in particular but as a symbol of the sun-god. Mark Lehner, for instance, writes, ‘The lion was a solar symbol in more than one ancient Near Eastern culture. It is also a common archetype of royalty. The royal human head on a lion’s body symbolises power and might controlled by the intelligence of the pharaoh, guarantor of cosmic order, Maat.’

54

All Egyptologists do agree, however, that the Sphinx was created during the Fourth Dynasty, and none of them can deny, of course, that it has the body of a lion and the head of a man or king and that it was made to gaze due east at the horizon, where the sun rises at the equinoxes. Not unexpectedly, in the Pyramid Texts the dead king is beseeched to join or become Horakhti in the eastern horizon at sunrise. Accordingly, Selim Hassan concluded that

Then came the occasion when the Egyptians wished to create an imposing image of their God-king, who after his death was called Horakhti - ‘Horus the Dweller in the Horizon’ - the Lord of Heaven. How to represent him? The idea of using the form of the lion probably occurred first, but did not quite meet the need, for the lion had come to be associated in their minds with ferocity as well as kingship, and they wished to represent a wise and powerful, but beneficent deity. It is perhaps in this manner that they evolved the form of the Sphinx, which displays the grace and terrific power of the lion and the superior intellectual power of man.

He further explained that

. . . in the beliefs of the Egyptians, the king was the earthly representation of this god, and we have proof that in the very early period the dead king was especially called Horakhti. When Khafra cut the Great Sphinx, it was made in his likeness, that is to say in the likeness of Horakhti, with whom he was identified.

55

As far as Hassan was concerned, the equation was simple and straightforward: Horakhti was identified with a lion; Khafra built the Sphinx; the dead Khafra was identified with Horakhti; the Sphinx was the guardian of Khafra’s tomb; the Sphinx must be, by all logic, a representation of the dead Khafra as Horakhti. It should be noted that in passages from the Pyramid Texts quoted earlier, we are told that the king joined not just Ra, i.e. the sun, but also Horakhti in the eastern horizon at dawn when the ‘Waterway is flooded’, i.e. during the summer solstice time of year when the Nile floods. At the epoch of Khafra this was the time of year when the sun was in the constellation of Leo. Leo is a lion constellation. The image of Horakhti is a lion. The Sphinx is a solar symbol. The conclusion must be, by all common sense, that Horakhti is Leo and that the Sphinx of Giza represents the sun-god Ra ‘coalesced’ with Horakhti in the Fourth Dynasty, which is when Egyptologists such as Wilkinson, as we shall see later on, say this ‘coalescing’ or synchretisation took place!

56

Oddly, however, such straightforward logic does not always work with Egyptologists. As a matter of fact, the idea that the Sphinx might be a symbol of the sun in Leo is one of the most vilified in this profession. But why?

56

Oddly, however, such straightforward logic does not always work with Egyptologists. As a matter of fact, the idea that the Sphinx might be a symbol of the sun in Leo is one of the most vilified in this profession. But why?

Other books

Summer Fling (Players of Marycliff University Book 1) by MacMillan, Jerica

Amazon Awakening by Caridad Piñeiro

Don't Drink the Holy Water by Bailey Bradford

Moving Target by McCray, Cheyenne

Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead by Barbara Comyns

When Saint Goes Marching In by Laveen, Tiana

Lord of the Blade by Elizabeth Rose

Secret Society by Tom Dolby

Camping Chaos by Franklin W. Dixon

A Harem of One [The Moreland Brothers 3] (Siren Publishing Allure) by Jennifer Willows