The Egypt Code (22 page)

Authors: Robert Bauval

It was the scholar Anne-Sophie Bomhard who found it necessary to remind Egyptologists that the ancient Egyptians were ‘masters of observing Nature’ and that they especially observed the motions of the sky. Egyptologists in general do not disagree with her. But they will point out that observing the motions of the sky is one thing, but meticulously studying and recording its various cycles is quite another matter. For that you have to be an astronomer, and it was not until the Greeks came to Egypt in the fourth century BC, Egyptologists insist, that any serious astronomy was performed there. According to one such academic, the Egyptians ‘borrowed their knowledge of the Signs of the Zodiac, together with much else, from the Greeks’, while another asserts with equal scorn that ‘Egypt did not contribute to the history of mathematical astronomy’.

14

Could it be that the entrenched belief that all science and all philosophy stems from Greece is the cause of this disdain for the ancient Egyptian sky-watchers?

14

Could it be that the entrenched belief that all science and all philosophy stems from Greece is the cause of this disdain for the ancient Egyptian sky-watchers?

Notwithstanding such subjective bias, there is a serious flaw in this reasoning. For while Egyptologists insist that astronomy was taught to the Egyptians by the Greeks, the Greeks themselves insist that it was the other way round. The great Plato, for example, could not stop marvelling at the wisdom of the Egyptian priests and how they ‘spent their nights observing the stars’.

15

Strabo wrote how the Egyptians ‘excelled in the science of astronomy’.

16

And Diodorus lauded the Egyptian priests and reported how ‘Democritus lived with the priests of Egypt for five years and learned many things from them related to astronomy.’

17

Then there is Iambilicus reporting how Pythagoras sojourned 20 years with Egyptian priests, and that ‘it was from them that he learnt the science for which, later, he was deemed a genius’.

18

Iambilicus also tells us how ‘Pythagoras visited all the temples of Egypt with much ardour . . . (and) he was much admired by the priests with who he lived, learning from them all things with great diligence . . . mostly geometry . . . and astronomy.’

19

15

Strabo wrote how the Egyptians ‘excelled in the science of astronomy’.

16

And Diodorus lauded the Egyptian priests and reported how ‘Democritus lived with the priests of Egypt for five years and learned many things from them related to astronomy.’

17

Then there is Iambilicus reporting how Pythagoras sojourned 20 years with Egyptian priests, and that ‘it was from them that he learnt the science for which, later, he was deemed a genius’.

18

Iambilicus also tells us how ‘Pythagoras visited all the temples of Egypt with much ardour . . . (and) he was much admired by the priests with who he lived, learning from them all things with great diligence . . . mostly geometry . . . and astronomy.’

19

But what of the discovery of precession? Do any of these ancient Greek scholars tell us that it was not one of them but rather the ancient Egyptians who discovered it? There is one at least. For although this discovery is generally attributed to Hipparchus of Rhodes (

c

. 127 BC), there is the great scholar Proclus Diadochus of Nicea (AD 410-485) who tells us forcefully that this is not true at all, and that the discovery belongs fair and square to the Egyptians. And to boot, Proclus insists that it was the great Plato who had said so. In Proclus’s own words:

c

. 127 BC), there is the great scholar Proclus Diadochus of Nicea (AD 410-485) who tells us forcefully that this is not true at all, and that the discovery belongs fair and square to the Egyptians. And to boot, Proclus insists that it was the great Plato who had said so. In Proclus’s own words:

Let those who, believing in observations, cause the stars to move around the poles of the zodiac by one degree in one hundred years toward the east, as Ptolemy and Hipparchus did before him know . . . that the Egyptians had already taught Plato about the movements of the fixed stars. Because they utilised previous observations which the Chaldeans had made long before them with the same results, having again been instructed by the gods prior to the observations. And they did not speak just a single time, but many times . . . of the advance of the fixed stars.

20

The Czech Egyptologist Zbynek Zaba, who is well known for his studies in ancient Egyptian astronomy, had this to say about Proclus’s commentary:

Until now it has been believed that the Egyptians were not aware of the movement of the fixed stars caused by the precession of the axis of the planet. I believe that the diagrams of the Egyptians of the starry sky tend to prove the contrary. Proclus Diadochus affirms that the Egyptians discovered not only the movement of the fixed stars but also the precession of the equinoxes which is another consequence of the precession of the axis of the planet. To this we have no proof so far, and it is possible that the discovery of the precession of the equinoxes rests entirely with Hipparchus. It is nonetheless more probable, in my opinion, that even this discovery had been made by the ancient Egyptians, and that Proclus was well informed . . .

21

But how well informed

was

Proclus? First it should be pointed out that he was no dilettante. This was especially true when it came to matters regarding the writings of Plato. So his claim that the Egyptian priests taught Plato the secrets of precession was not something that he plucked from thin air.

was

Proclus? First it should be pointed out that he was no dilettante. This was especially true when it came to matters regarding the writings of Plato. So his claim that the Egyptian priests taught Plato the secrets of precession was not something that he plucked from thin air.

Proclus was born in AD 411 in Constantinople (now Istanbul), and for many years he had been a student of the great Neoplatonic philosopher Olympiadorus of Alexandria. Later he also studied under the great Plutarch and Syrianus at the famous academy in Athens which, as is well known, was founded by Plato. Proclus eventually became the head of the Platonic academy and remained an important figure there until his death in AD 485. While at the academy, he specialised in the works of Aristotle and Plato, which were then all available to him. In one of Plato’s works the great philosopher had written of ‘the beauty and clarity of the skies in Egypt’ and how this allowed the Egyptians to see ‘all the stars’, which they had observed and studied ‘for 10,000 years, or an infinity number of years so to speak’. Plato was not alone in attributing great antiquity to the ancient Egyptian sky-watchers. Other scholars, such as Aristotle, Seneca, Diodorus, Simplicius and Strabo, also wrote of how the Egyptian priests had carefully studied the stars for thousands of years.

22

If this is true - and there is no reason to think otherwise - then it is difficult, indeed impossible, to see how the avid Egyptian stargazers would not have noticed over a few generations the apparent movement of the fixed stars caused by the effect of precession.

22

If this is true - and there is no reason to think otherwise - then it is difficult, indeed impossible, to see how the avid Egyptian stargazers would not have noticed over a few generations the apparent movement of the fixed stars caused by the effect of precession.

The possibility that precession was known to the ancient Egyptians was first seriously brought up in the late 1820s by the French astronomer Jean-Baptiste Biot, a member of the prestigious Académie Française. Biot was convinced not only that the ancient Egyptian priests were aware of the precession of the equinoxes, but also that they had tracked its effect through the ages:

. . . they would have been able, even in the course of a few years, to recognise that the course of the rising and setting points of different stars were changing place on the horizon after a certain period of time, were no longer at the same terrestrial alignment. They would thus have been able to verify the general and progressive displacement of the celestial sphere relative to the meridian line, that is to say the most apparent effect of the precession of the equinoxes.

23

The next scholar to entertain such views was the British astronomer Sir Norman Lockyer. According to Lockyer:

The various apparent movements of the heavenly bodies which are produced by the rotation and the revolution of the earth, and the effect of precession, were familiar to the Egyptians, however ignorant they may have been of their causes; they carefully studied what they saw, and attempted to put their knowledge together in the most convenient fashion, associating it with their strange imaginings of their system of worship.

24

Recently the Russian astronomer Dr Alexander Gurshtein, vice-president of the History of Astronomy of the IAU (International Astronomical Union), used his full academic stature to support the idea that the ancient Egyptians were aware of the shift of the vernal point against the fixed stars and, consequently, were aware of the precession of the equinoxes.

25

Even more recently these same views were expressed by the Italian astronomer Giulio Magli, an associate professor at the Department of Mathematics at Milano Politecnico.

26

Even the usually sceptical American astronomer E.C. Krupp was open to this idea when he wrote that

25

Even more recently these same views were expressed by the Italian astronomer Giulio Magli, an associate professor at the Department of Mathematics at Milano Politecnico.

26

Even the usually sceptical American astronomer E.C. Krupp was open to this idea when he wrote that

. . . circumstantial evidence implies that the awareness of the shifting equinoxes may be of considerable antiquity, for we find, in Egypt at least, a succession of cults whose iconography and interest focus on duality, the bull, and the ram at appropriate periods for Gemini, Taurus, and Aries in the precessional cycle of the equinoxes.

27

Krupp added, however, that ‘whether the Egyptians were fully aware of precession is one thing; whether they responded to it is another.’

28

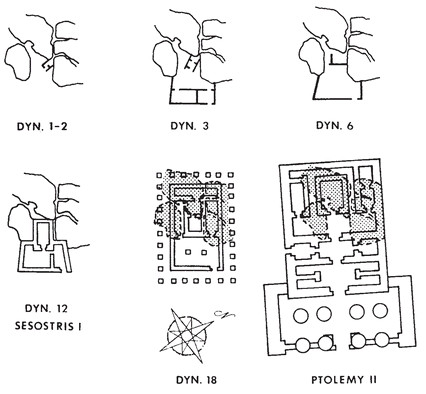

Since those words were written, further research has shown that the ancient Egyptians did, in fact, respond to it by changing the axis of many temples that had been aligned to the rising of Sirius. We know at least three such examples where they did this over hundreds of years: the temple of Satis on Elephantine Island; the temple of Isis at Dendera, and the temple of Horus on Thoth Hill near Luxor.

28

Since those words were written, further research has shown that the ancient Egyptians did, in fact, respond to it by changing the axis of many temples that had been aligned to the rising of Sirius. We know at least three such examples where they did this over hundreds of years: the temple of Satis on Elephantine Island; the temple of Isis at Dendera, and the temple of Horus on Thoth Hill near Luxor.

Plan of the Evolution of the Satet Temple on Elephantine Island

Elephantine Island is just a mile or so downriver from the first cataract on the Nile near the modern town of Aswan.

29

The Nile at this point is at its widest and its water is crystal clear with a wonderful deep blue tone. Its banks are lined with tall palm trees and multicoloured bougainvillaea and oleanders. On the west bank rise high sand dunes that catch the pink light of the early morning sun. White egrets fly along the river and water buffaloes float lazily in the shallows, while children swim around and women squat by the water’s edge to do their laundry. The gift of the Nile is well appreciated here at Elephantine. Here the river truly excels.

29

The Nile at this point is at its widest and its water is crystal clear with a wonderful deep blue tone. Its banks are lined with tall palm trees and multicoloured bougainvillaea and oleanders. On the west bank rise high sand dunes that catch the pink light of the early morning sun. White egrets fly along the river and water buffaloes float lazily in the shallows, while children swim around and women squat by the water’s edge to do their laundry. The gift of the Nile is well appreciated here at Elephantine. Here the river truly excels.

Elephantine was once the capital of the First Nome of Upper Egypt and was sacred to Khnum, the ram-headed creator god who fashioned mankind on his divine potter’s wheel. It was also sacred to his elegant consort, the goddess Satet or Satis (in Greek), who was closely identified with the Nile’s flood. It is this goddess who predominated here at Elephantine, because throughout ancient times this place was considered the mouth of the netherworld or Duat from where the Nile’s flood emerged.

30

Satis was also the guardian of the southern frontier of Egypt, protecting it from invaders with her divine bow and arrow. Not surprisingly, she was later identified with the Greek Artemis, the divine huntress.

30

Satis was also the guardian of the southern frontier of Egypt, protecting it from invaders with her divine bow and arrow. Not surprisingly, she was later identified with the Greek Artemis, the divine huntress.

Satis’s name is first attested on jars found under the Step Pyramid at Saqqara. This should be of particular interest to us, because she was also identified with the star Sirius, the herald of the Nile flood. The reader will recall how in Chapter One we associated the Step Pyramid at Saqqara with the star Sirius, a fact also attested by the name of the pyramid: ‘Horus is the Star at the Head of the Sky’. Satis is mentioned in the Pyramid Texts, where she is said to purify the dead king with the divine flood water brought in jars from Elephantine.

31

She is usually shown as a tall, slender woman wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt from which protrude two antelope horns. On the front of the crown is often seen a five-pointed star, which almost certainly represented Sirius, a symbol of the flood. There is also an assortment of epithets attesting to Satis’s close connection with the stellar world and implying her cosmic identity as Sirius: ‘Lady of Stars’; ‘Mistress of the eastern horizon of the sky, at whose sight everyone rejoices’; ‘The Great One in the Sky, ruler of the Stars’; ‘Satis who brightens the two lands with her beauty’ and so on.

32

31

She is usually shown as a tall, slender woman wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt from which protrude two antelope horns. On the front of the crown is often seen a five-pointed star, which almost certainly represented Sirius, a symbol of the flood. There is also an assortment of epithets attesting to Satis’s close connection with the stellar world and implying her cosmic identity as Sirius: ‘Lady of Stars’; ‘Mistress of the eastern horizon of the sky, at whose sight everyone rejoices’; ‘The Great One in the Sky, ruler of the Stars’; ‘Satis who brightens the two lands with her beauty’ and so on.

32

Elephantine Island is just two kilometres long and half a kilometre wide. On it were found the remains of several ancient temples, the largest being the temple of Khnum, located on the south side of the island. North of Khnum’s temple is the smaller temple of Satis. Archaeological evidence shows that the island has been inhabited since predynastic times, and a team from the German Archaeology Institute of Cairo discovered underneath the temple of Satis evidence of earlier temples going back to the early dynastic period. Indeed, the peculiarity of the temple of Satis is that it is built on the ruins of several other temples going down in tiers like some giant wedding cake, starting at the bottom with an early dynastic shrine dated to about 2900 BC, then an Old Kingdom shrine dated to 2200 BC, then a Middle Kingdom shrine dated to about 1800 BC, then a New Kingdom shrine, and finally the restored Ptolemaic temple which is seen today and dated to the second century BC.

33

33

Other books

Hannibal: A Hellenistic Life by Eve MacDonald

If You Wrong Us by Dawn Klehr

Unremarkable (Anything But) by Zart, Lindy

Steal: A Bad Boy Romance by Whiskey, D.G.

City Lights (Satan's Sinners M.C. Book 1) by Kay, Colbie

Mammoth Books presents Merlin's Gun by Alastair Reynolds

Starfire by Kate Douglas

Fate Book Two by Mimi Jean Pamfiloff

Hot Pursuit by Sweetland, WL

Chameleon Soul (Chequered Flag #1) by Mia Hoddell