The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars (59 page)

Read The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars Online

Authors: Jeremy Simmonds

Just as 1978 had begun with the fatality of a Chicago-born musician, so would 1979 – although Donny Hathaway’s death was apparently no accident. Raised by his grandmother in St Louis, Missouri, young Hathaway was considered an intellectual among the soul fraternity. Gospel-turned-cocktail-jazz singer Hathaway had started as a music-theory major, attracting the interest of Curtis Mayfield, who employed the graduate as a producer at his Curtom label. With his foot firmly in the door, Hathaway began his own recording career with the duet ‘I Thank You Baby’ (1969) with June Conquest, and composed sophisticated tunes both for himself and others such as Aretha Franklin. It would be, though, his work with soul-ballad queen Roberta Flack – his former classmate at Howard University, Washington, DC – that resonated most with fans: ‘You’ve Got a Friend’ (1971, written by James Taylor) and, in particular, ‘Where is the Love?’ (1972) were US hits and suggested there might be more between the pair than mere professional empathy.

Sadly for Hathaway, his love for Flack was – apparently – unrequited. During the seventies, the singer suffered frequent bouts of depression, not least when their working relationship began to suffer as early as 1973; on his own, Hathaway found the going tougher and retreated from the limelight, though partial reconciliation with Flack led to another album in 1977. A single, ‘The Closer I Get to You’ (1978), became their biggest hit together, just edged out of US number one by The Bee Gees. In January 1979, the pair recorded more songs in New York, all their earlier differences seemingly patched up – but this wasn’t enough for Hathaway. Distraught that he could never be with Flack (who was happily married with children), he made a shocking decision. After a final plea to Flack, Hathaway allegedly removed the glass from a window while she was otherwise occupied, stepped out on to the ledge and dropped from the fifteenth floor of the Plaza Hotel. His body landed on a second-floor ledge.

Opinion was divided after the ensuing inquest: while the Reverend Jesse Jackson (who read Hathaway’s eulogy) suggested that this was no suicide, the coroner remained adamant that ‘no adult ever fell from a waist-high window’. One bizarre fact that emerged was that Hathaway apparently made a habit of preaching from hotel windows – and had been ejected from more than one hotel for doing so. Flack & Hathaway’s poignantly titled ‘Back Together Again’ (1980) gave the singer a sizeable posthumous hit, while his surviving daughter, Lalah, enjoyed musical success during the nineties.

FEBRUARY

Friday 2

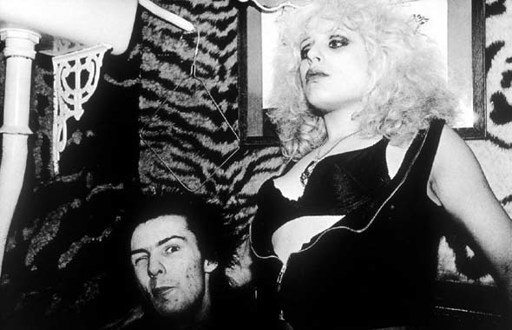

Sid Vicious

(Simon John Ritchie - Lewisham, London, 10 May 1957)

The Sex Pistols

‘I’ll die before I’m twenty-five. And when I do, I’ll have lived the way I wanted to.’

Sid Vicious, in 1978

If The Ramones dumbed down punk with a cartoon-like frenzy of action, then uberfan Sid’s means of achieving the same were just the opposite – his sullen, deliberately self-destructive personality seemed to hit the spot as far as the nihilistic end of the market was concerned. Whether punk was ever meant to be about this is open to debate, but there’s little doubt that Vicious was marketed as an icon on whom followers could impose whatever fantasy they wished. Was Vicious a mass of contradictions? Rose-tinted minority opinion paints him as a reluctant intellectual who quoted Wilde, more remember him as a volatile attention-seeker who only wanted to be a rock star – a prize for which he was prepared to die.

Stories about his young life vary from the lurid to the downright ludicrous, but there’s little doubt that Simon John Ritchie, at some point or other, caused harm to old women, young women, the odd journalist and an assortment of animals. In his defence, he had a deeply unsettled upbringing: his father walked out on his bohemian mother, Anne, when Simon was just two years old, and his stepfather, a middle-class Kentish man called Chris Beverley, died within months of his mother’s second marriage, which placed him into a rough Tunbridge Wells secondary modern rather than the private education in which he might have ended up. At this school, the now-renamed John Beverley had few friends. For one, he was volatile and unpredictable – but, more significantly, he couldn’t take friends home because his mother had used heroin since the early sixties. By the time her son was sixteen they were known to shoot up together.

Returning to London in 1974, Beverley spent time around Kingsway College and had settled sufficiently to acquire a couple of allies in two other Johns, Wardle (Jah Wobble) and former Hackney school-friend Lydon (Johnny Rotten): together they would drink copiously and get up to little more than check out each other’s music collections (Beverley was, believe it or not, a fan of Brian Eno, The Pink Fairies and Weather Report, among others). But, outside this, his disturbing need for drugs was what cemented his wayward legend for the couple of years before he joined the Sex Pistols. His behaviour became increasingly malevolent as a result: in October 1975, Beverley sold some powder (which turned out to be toilet cleaner) at an Oxford party under the premise that it was some of the amphetamine he was widely known to be taking at this time – it very nearly killed its recipient. Later, the out-of-control Beverley boasted to friends of mugging an old lady at knifepoint in an alleyway. As if that weren’t enough, he then (famously) set about

NME

scribe Nick Kent with a bike chain at the 100 Club (he later blinded a girl in one eye when he threw a pint glass at another early Pistols gig there – for which he spent a paltry week in remand). So, when

was

music going to play any part in this rock ‘n’ roller’s life?

Well, soon after – to a degree. As the Pistols – Johnny Rotten (vocals), Steve Jones (guitars), Paul Cook (drums) and, at this stage, Glen Matlock (bass) – began to gain notoriety, a jealous Beverley fashioned his own band, Flowers Of Romance, with three women, two of whom were future members of The Slits, Viv Albertine and Paloma ‘Palmolive’ Romero. When this fell apart after Beverley expressed a ‘liking’ for the Nazis, he spent some time behind the kit of the fledgling Siouxsie & The Banshees … until they found a proper drummer. But Vicious – as he was finally to be known – was not to be denied. Despite wide disapproval from their peers, on 3 March 1977 the Sex Pistols and manager Malcolm McLaren kicked out Glen Matlock (the man who had written most of debut single ‘Anarchy in the UK’) to replace him with Sid Vicious. Who had never played bass in his life. It was just one more tabloid-taunting move amid the taking of nearly £150K from three major labels inside six months as the band began its ‘cash from chaos’ plan in earnest. The records were admittedly great at this point – ‘God Save the Queen’, ‘Pretty Vacant’ and ‘Holidays in the Sun’ all went Top Ten (the first of these would probably have been a UK number one but authorities wouldn’t allow that) as Britain decided between monarchy and anarchy in the heady summer of 1977.

Although he’d made cursory attempts to learn his instrument, The Sex Pistols’ newest acquisition had begun to fall apart as early as April 1977, when punk’s most notorious groupie, Nancy Spungen, arrived in his world. Spungen was a rebellious Pennsylvanian who had attempted suicide on at least one occasion and had used smack since her early teens; she’d even been to known to strip and sleep around for her habit. A former cashier at CBGB’s, Spungen had initially come to London with the intention of bedding one of The New York Dolls, but, on being banned outright from even approaching former drummer Jerry Nolan, she turned her attention to Sid. Despite his outer bravado, Vicious was naive, weak-willed and quite possibly still a virgin: to him, with his blurred vision and increasingly warped perception of reality, Spungen probably looked like a goddess, a rock chick to out-rock-chick them all. Under her guidance, Vicious slipped into heroin meltdown as the Pistols folded in on themselves during the ill-fated 1978 US tour. By now his deranged ‘act’ consisted of calling American audiences ‘faggots’ and making himself bleed on stage, the bassist’s amp generally switched off while a session-player strummed behind the scenes. Then, one afternoon in January, Vicious awoke from a drug-related coma in a New York hospital to discover that Rotten, Cook and Jones had all called time on what they considered an increasingly wretched project. Now – he thought – he needed Spungen more than ever.

Sid and Nancy: Punk’s ‘Posh and Becks’

‘I’m glad he died. Nothing can hurt him any more.’

Anne Beverley, Vicious’s mother

Despite the breakup of one of the most potent bands of all time, the remainder of the year was not entirely uneventful for Sid Vicious: he recorded a memorably nihilistic rendition of ‘My Way’, which illuminated that otherwise miserable movie

The Great Rock

V

Roll Swindle

– and in August he moved back to New York with Spungen. The idea was to quit heroin and reignite Vicious’s career (with Spungen, somehow, as his manager). He played a few gigs – with various ex-Dolls, and even Mick Jones of The Clash, as back-up – but New York remained largely unsympathetic to a performer and his muse whose reputations it remembered only too damn well.

So, with their shared heroin and methadone habit wrapping them in a warm blanket, punk’s most notorious couple hid themselves away in Room 100 of the $17-a-night Chelsea Hotel, West 23rd Street, New York – a once-glamorous residence that now reserved its lower floors for supposed artisans and junkies. It all came to a shocking, if predictable, climax when, sometime between 5 and 9 am on the morning of 12 October, Vicious entered the bathroom to find Spungen in her underwear, slumped by the lavatory, apparently stabbed to death. The murder weapon he recognized as his own knife – which she had recently bought him for protection from frequent attacks. Understandably in shock from the event, Vicious confessed on arrest that

he

had done it because he was a ‘dirty dog’ – only to deny responsibility on further questioning. It is widely known that various suppliers and users came and went from Room 100 that night – and that on top of his usual intake, Vicious had dropped as many as nine Tuinols (barbiturates) – but to this day nobody really has a firm notion of what transpired. Many believe that criminal friends of a supplier had robbed them and attacked Spungen, while others think there may have been a suicide pact; Vicious’s mother – who despised her son’s girlfriend – maintained until her own death (from a 1996 overdose) that Spungen stabbed herself. Vicious was charged and incarcerated at Riker’s Island Prison, and although he was bailed at a cost of around $50K, he soon found himself back behind bars. Ten days after his release, he attempted suicide, which saw him placed in a psychiatric unit at the Bellevue Hospital. Vicious was clearly traumatized by the death of Spungen, but the shock of her death was still insufficient to revise his behaviour. Before his own demise, he found time to acquire a new girlfriend (actress Michelle Robinson, who herself had recently lost a partner) and to inflict another serious eye injury, this time on Patti Smith’s brother Todd in January 1979. For this, he received a sentence of fifty-five days – which, of course, he was never to serve.

‘Sid actually did nothing. Excellent person, but drugs turned him into an unpleasant Mr Hyde.’

Johnny Rotten

Celebrating his second bail in just three months, Vicious threw his last party on 2 February in the company of Robinson, various junkie friends and Anne Beverley – who had been in America for a while – at Robinson’s Greenwich Village apartment. Although Vicious had been detoxified while serving time, he, his friends and his mother saw no reason not to get him a fix. The heroin was, according to its pusher, almost 100 per cent pure; on his first hit, Vicious passed out but came round. He got up, spoke to his mother, and then – as she and Robinson slept – shot up again. His vast second dose killed him during the night, while Robinson slept beside him in ignorance. He was cremated in New York three days later. Although a verdict of suicide was passed, the blame for his (and Spungen’s) death has consistently been shoved from pillar to post in the twenty-seven years since. Put simply, Sid Vicious was never going to be saved. He wanted the legacy too much.