Read The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History Online

Authors: Trevor Yorke

The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History (10 page)

FIG 6.7:

A diagram showing a pollarded and a coppiced tree

.

Another source of timber was wood pasture, which was usually common land with trees and open spaces for grazing. To avoid the livestock eating the young shoots growing on the trees, they were pollarded (i.e. the branches cut back to above the reach of the grazing animals). Pollarded willows were a common sight along the river bank, with the cropped branches (osiers) used for basket weaving. It is worth noting that a coppiced or pollarded tree will often be up to two or three times older than an unmanaged tree of the same species, although willows are rarely very old. This also applies to those trees which were cut back and laid to make traditional hedges. Identification of these around a village may help in establishing old from new boundaries and previous land use.

Increased demand for land and timber since the 18th century, especially in the boom years of the mid-Victorian period and since the Second World War, has seen the demise of much woodland. A curved or irregular-shaped area divided up into small fields may indicate where trees were grubbed up and put under the plough. Others were enclosed or converted to timber

production, the more natural mix of flora and fauna being sacrificed in preference for the growth of one particular tree. Industries like shipbuilding, tanning, iron, furniture and mining also played their part in the decline of semi-natural woodland although many still managed the trees with coppicing and replanting to maintain their supply of fuel and timber.

FIG 6.8:

A traditional method of forming a barrier was by cutting trees low down and laying branches flat between uprights. Sometimes mature trees can be found in old boundaries with trunks running horizontal for a short way and then shooting up into a mass of smaller branches, indicating that this was formerly a hedge laid in this way and that the boundary and tree may be very old

.

In the 20th century the decline of grazing on those commons and wastes which survived the enclosure movement, permitted a secondary growth of trees to become established as there were no animals to eat the young shoots. Disused industrial and military land can also become scrub in an amazingly short time, and then develop into woodland. The humps and bumps which you probably would not think twice about in a wood today can be worth investigating as when viewed on old maps and photographs they can reveal a surprisingly recent yet forgotten landscape.

FIG 6.9:

Along a ridge of hills as here in the Chilterns, parishes were often shaped in long strips reaching up to the tops so that they would take in the woodland, as it was a vital asset to be shared by villagers for buildings and fencing

.

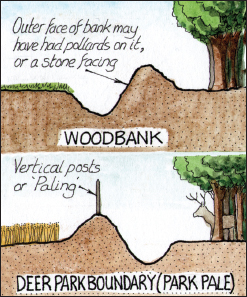

FIG 6.10:

To protect woodland from grazing animals a bank would have been raised around its perimeter with a ditch on the outside face. These can still be found sometimes within a wood showing that the area of trees has increased since medieval times. A deer park boundary had the bank beyond the ditch making it hard for animals to jump out

.

Deer parks

Their passion for hunting inspired the medieval gentry to create their own deer parks, which would usually be established within existing woodland on the lord’s own demesne land. It was enclosed by a ditch and beyond this a

bank with a timber fence or hedge along the top to prevent the precious animals escaping; they would only be released into the surrounding land at the time of a hunt. At their peak there were some 3,000 parks across England which could be up to 200 acres in size, but by the 16th century they had fallen from favour and many became incorporated within later landscaped garden schemes or were grubbed up for farming. Their boundaries, which were often a rough circle in plan, can still be identified on maps divided up by later fields and the remains of their internal ditches and external banks can sometimes be found today.

With the loss of parks and woodland, hunting deer declined and firstly the hare and then after the Restoration in 1660, the fox which had previously been regarded as an inferior target, became a popular quarry. Stables and kennels to keep the horses and hounds were built and fox coverts or artificial earths created to encourage the foxes to breed. Shooting also became popular, with gamekeepers protecting open moorland and woodland for the breeding of birds like grouse and pheasants, especially in the agricultural depressions of 1820–1840 and 1870–1900. At the time of the shoot men would drive the birds out of the scrub and trees towards the gunmen standing in the surrounding fields. Another favourite pastime of the rich was horse racing and many courses were laid out in the 17th and 18th centuries, for instance on the now sacred lands at Port Meadow in Oxford and Runnymede in Surrey! Most of these have gone but their presence may be preserved on old maps or in field names.

FIG 6.11:

The ridge running from the bottom right corner in a curve and off up the left edge of the ploughed field is an old deer park boundary with the faint impression of the ditch on its inner side (right-hand side of bank). This would have enclosed a park similar to that in the top left corner of Fig 2.7

.

FIG 6.12:

With the growing popularity of shooting in the late 19th century, open moorland like this below Kinder Scout in Derbyshire became a breeding ground for grouse. The square patterns in the scrub behind the white lodge are where it has been burnt out to encourage growth of young shoots for the birds

.

It was not until the late 16th century that large-scale garden schemes designed for pleasure and appearance rather than hunting and growing herbs began to be laid out around new country houses. These later Tudor gardens were influenced by the Renaissance and would usually have a rectangular area enclosed by a bank with the internal space set out in blocks of low hedges containing geometric designs. The patterns were intended to be viewed from above, so a mound sometimes with a timber shelter on top was raised as a viewing point (these can often be confused with castle mottes and windmill mounds). In the early 17th century gardens were influenced by the latest French, Dutch and Italian designs. The general scale increases and features like terraces, topiary, statues and water features appear, although the designs are still very geometric.

By the 1730s a new movement towards a naturalistic landscape inspired by the paintings of classical mythology, resulted in the laying out of parkland with carefully positioned clumps and bands of trees, serpentine lakes, follies and temples. Gone were the geometric flower beds and terraces, now sweeping lawns drew the eye over idyllic settings designed by famous gardeners like ‘Capability’ Brown, in which the wealthy could entertain and impress their guests. By the late 18th century it became fashionable to have tall towers and follies positioned on distant hills so that when viewed from the country house it appeared that the owner’s lands stretched on forever.

FIG 6.13 POWIS CASTLE, POWYS:

A typical late 17th- and early 18th-century landscaped estate with terraces, a formal garden and open parkland beyond. Pasture today with isolated mature trees can often be old parkland even though the estate may have been broken up

.