Read The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History Online

Authors: Trevor Yorke

The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History (12 page)

FIG 7.5:

Milestones carved with destinations and mileages are another notable feature which can be found along old turnpike roads, and are marked by an ‘M.S.’ on Ordnance Survey maps. The destinations on them can indicate where the turnpike was going to, places which could have been of importance to the village or local lord at the time

.

Droving cattle and sheep from upland areas to the main cities, especially London, became important from the mid 17th until the 19th century. The driving of livestock was a planned project by licensed drovers and they kept to special routes which were preferably away from turnpike tolls and built-up areas. Ideally they would have grazing areas along the way and inns or farms where there was a field for the livestock to be impounded overnight and accommodation for the men. The railways ended the droving trade though the remains of routes especially in the uplands, the overnight stances identifiable by names like Halfpenny or Broad Field, and the inns and farms they stopped at, can still be traced today.

By the early 19th century more than 20,000 miles of roads were maintained by the turnpike trusts but their profits were eroded by canals and then critically by the railways. Most had gone out of business by 1880, the last one in 1895, with their responsibilities passing over to new local government. Yet despite the influence of the turnpike trusts, the majority of roads in the early 1800s were still little more than tracks without defined edges which were repaired by members of the parish. In 1835 the system changed to one where a rate was levied on the parish for their maintenance, and surveyors for the highways were appointed. The improved drainage and new methods of surfacing slowly filtered down to lesser roads but neatly edged modern tarmac routes only developed in the last 80 years as the car heralded a new boom time for our highways.

In the 21st century, major engineering works like new bridges, cuttings, and embankments have further relegated parts of old routes though these can still be found as parking spaces and tracks alongside many of them. Another place where the course of a main road may have changed is where it climbs a hill. Sometimes, a number of progressively straighter and shallow gradient routes can be found beside each other. Of greatest influence upon the village in the last century though has been the bypass. Although it can bring peace to the roadside inhabitants, the loss of passing traffic can ruin a shop or garage business, while the fields now enclosed by it are an easy target for the housing developer.

FIG 7.6:

The new roads laid out during Parliamentary enclosure were typically straight and set in a wide gap between the hawthorn hedges with grass verges and ditches either side like this road in Bucks. (Some turnpike roads were laid out in a similar way.) These are often mistaken for Roman roads

.

An inn providing refreshment and accommodation for travellers was a feature of many villages along important routes. The earliest may have been used by pilgrims as they were among the few who had any reason to travel great distances and many establishments were owned by monasteries who were also great producers of ale. As long-distance travel started to increase, other groups like merchants required places to stay overnight, so the numbers of inns increased. The boom in coach travel in

the 17th and 18th centuries resulted in the building of many new hostelries in the latest Classical style as modernity and architectural taste attracted a better type of customer. Those who could not afford to build from scratch refaced their old timber-framed structures with fashionable brick or stone façades to mask their humble origins, which only become visible as you pass beneath the archway and go and look around the back.

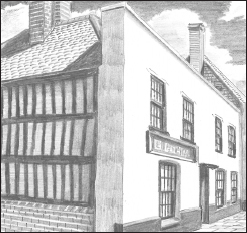

FIG 7.7:

A timber-framed building which has been re-fronted with a Classical façade in the 18th century. Windows not in a true horizontal line and an unsymmetrical façade are useful clues and a look at the side or rear of a building will usually reveal where this has happened

.

Fords

In the past most rivers and streams were wide and shallow, meandering through flood plains, rather than in tight contained channels as they are today. Fording these shallow waterways was the most practical way of crossing them although there may have only been a few suitable places along a stretch of river where the geology and depth permitted it. Hence some fords can be very old and may indicate that the route if not the adjacent settlement is of some antiquity.

The most common method of crossing a larger river before the Industrial Age was by ferry. This could either be simply a man and a rowing boat, or more often a flat-bottomed vessel would have been dragged across by a rope or chain fixed to both banks. Even where a bridge was built a ferry could continue and in some cases even replace

the permanent structure when it decayed. This could happen when the lord of the manor who had the right to charge for use of the ferry found this more profitable than having to finance the expensive construction or repair of a bridge.

FIG 7.8 SUTTON, BEDS:

A packhorse bridge and ford, the former being essential to keep trains of horses crossing in bad weather; the latter may have avoided a toll in summer! Although many fords have long since gone, the widening of the boundaries on one side can reveal where they once ran. The bridge in this view was found to have elm beams in its foundations which had supported the masonry for around 700 years

.

The remains of timber piles dating back into prehistory have been uncovered by archaeologists, showing that Bronze and Iron Age peoples were capable of building these large structures. The Romans built most of their bridges out of wood, but a few stone abutments along the line of Hadrian’s Wall show that the Romans did also erect arched stone structures across some major rivers.

Although many medieval bridges would have been built from timber, stone-arched structures began to become common from the 13th century; these major undertakings were often associated with an abbey, guild or church. The earliest had small semicircular arches with wide piers between, plain faces and probably a simple wooden rail along the top although some may have had no barrier at all. As they developed, pointed arches with ribs beneath became popular, being more flexible and using less cut stone. Cutwaters (pointed protrusions from the face of the bridge) were added to protect the structure at time of flood and create a refuge above for pedestrians, and stone parapets fitted along the top to prevent travellers falling into the water. By the 15th century, wider arches were being built using segmental arches and this form superseded pointed and semi circular types in the following centuries. Over wide river valleys causeways were built up approaching the crossing, sometimes being as impressive a monument as the bridge itself.

FIG 7.9:

In upland areas it was common for the more turbulent waters to be crossed by stepping stones or a clapper bridge where timbers or stone slabs were placed upon substantial blocks in the river. Most of these bridges usually date to recent centuries and many would have been rebuilt a number of times due to flooding. However, there are some which have been proved to be of greater antiquity

.

FIG 7.10:

A cut-away drawing showing how a medieval stone bridge may have been constructed, a process which could have taken many years or even decades to complete. It was common for floods to destroy even stone bridges and several have been rebuilt many times over, often with a different style arch replacing earlier types

.

FIG 7.11:

Early medieval bridges usually had round arches, sometimes with timber parapets (top – Medbourne, Leics). From the late 13th century the pointed Gothic arch became common, now with pointed cutwaters protruding out to protect the structure during floods (centre – Turvey, Beds). By the 15th century segmental arches which could span greater distances were being introduced (bottom – Kirkby Lonsdale, Cumbria). This example with ribs below was a common feature of most late medieval bridges

.

As trade increased towards the end of the medieval period so more items were transported by cart, but smaller loads could be carried more economically in packs strapped over a horse’s back. Where the routes crossed a river or stream, a packhorse bridge may have been built, a thinner version of its larger counterpart and probably with no parapets so they did not clash with the panniers. They were important even in good weather as horses can have the irritating habit of wanting to roll about in the water to cool down, damaging the goods, although many were alongside fords which continued to be used.