Read The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History Online

Authors: Trevor Yorke

The English Village Explained: Britain’s Living History (2 page)

FIG 1.4:

A map of England and Wales showing the approximate split between the lowlands (dark green) and highland regions (light green) and some of the key areas of building stone

.

FIG 1.5 SKARA BRAE, ORKNEY:

On the west coast of the Orkney mainland stood a number of sand dunes, one of which was known as Skara Brae. On a winter’s night in 1850 a vicious storm ripped the turf from this particular dune and exposed stone walls of houses set in decomposed waste known as midden. The local laird excavated the site and slowly uncovered four houses, complete with stone furniture. Yet it was not until 1930 that the full extent of what is now termed a ‘village’ was revealed. There were ten circular structures huddled together and linked by passages, the great age of which was not realised until modern scientific methods established that it was 5,000 years old

.

FIG 1.6 WEST STOW, SUFFOLK

:

Reconstructed buildings based upon excavations of a Germanic settlers’ village from AD 400–650

.

In the highland zone smaller enclosed farmsteads and hamlets were the most common, occasionally large enough to be termed a village. In the north they comprised circular houses surrounded by a ditch and bank or a stone wall, while in the south-west slightly different types known as rounds and courtyard houses were widespread. Chysauster, four miles north of Penzance, is a famous example of the latter. Finally, in both regions, there were vici, civilian settlements which were established outside military forts where soldiers could buy supplies, drink or pray.

After the recalling of the Roman legions in AD 410 there is little evidence for the traditional picture of Germanic armies marauding across the country and burning down the Britons’ villages. After AD 450, the incoming Angles and Saxons did establish new settlements, mainly in eastern England, but these seem to have been scattered formless collections of timber huts and were only used for a number of generations. In the upland regions there was little change until the 8th century except for those settlements which were dependent on the Roman military presence, where general abandonment is indicated, especially along Hadrian’s Wall. Yet out of the mists of these so-called Dark Ages, new villages of a more familiar nucleated form appeared. The probable reasons for them being established and how they originally appeared will be explained in the next chapter.

FIG 1.7:

An impression of an early Saxon settlement which was little more than a collection of scattered farmsteads. How these and more established hamlets would form into villages is covered in the next chapter

.

HAPTER

2

| The First Villages |  |

FIG 2.1:

An image of a new village formed in this period with its church dominating the single-storey, peasant longhouses around it. This chapter will look at the reasons this new type of settlement developed, the forms they took and the society which evolved within them

.

A

s England started to emerge from the Dark Ages we find the large kingdoms of firstly Northumbria, then Mercia and finally Wessex, vying with each other for supremacy. King Alfred of Wessex and his sons came to control most of the country and restricted Viking incursions to a strip of land to the east known as Danelaw. This unity was lost

under King Ethelred the Unready and during the first half of the 11th century England was alternately under Danish or Anglo-Saxon rule until 1066, when the invading Normans, themselves of Viking origin, took control. To pay back his loyal supporters William the Conqueror granted the estates of the Anglo-Saxons to his barons, who in turn built castles on their new manors as powerful symbols designed to quell any thoughts of rebellion. When the natives rose against them, as they did three times in the Northumbrian territory, William wreaked terrifying revenge by systematically destroying their villages in an act known as the ‘Harrying of the North’. The Conqueror’s lasting testimony, though, is the Domesday Book which he commissioned to record the value of manors (not actual villages) so he could calculate how much tax to charge them.

FIG 2.2 PEVERIL CASTLE, DERBYS:

Founded by one of William the Conqueror’s most trusted knights, this castle was strategically placed to control an important lead-mining area. The stone keep in this view was erected by Henry II as the castle had fallen into Crown hands after the civil war of King Stephen’s reign. Shortly afterwards a planned settlement with a central church and market place was built as an investment in the valley below. Castleton never grew beyond the size of a village but still has the original grid plan and outer ditch visible

.

William’s sons produced no lasting line of succession and from 1135 to 1154 King Stephen and the Empress Matilda, daughter of Henry I, fought for the throne in a civil war which saw the collapse of central power. Local barons were quick to increase their privileges and power amid the anarchy, but despite further disputes between the Crown and its lords, the 12th and 13th centuries were a boom time which saw the population more than double to a peak of around 5 to 6 million. This was only possible because of an increased output in farming.

Great changes occurred in the ownership and layout of agricultural land in this period, the reasons for and details of which are still not clear today. The appearance of villages replacing scattered farmsteads and hamlets seems inexorably tied in with this reorganisation.

In the late Saxon period most of the country was divided into large estates, some owned by royalty, others having been granted to the new monasteries. At the centre of these estates was the

caput

, which might be a hall or palace, perhaps with an associated hamlet or village, where produce and manpower was brought together from the subsidiary settlements around it. The land was divided up into fields close to the settlements for the growing of crops, and outfields further away for grazing and resources. Caputs were sometimes established on old Roman villa sites or within disused Iron Age hill forts, demonstrating continuity if not consistent use.

Within these estates there would have been all the agricultural and natural resources required by the local lord, which has led to them being called ‘multiple estates’. Although there are regional variations and names, this type of settlement has been recognised at numerous sites all over the country. It is also worth noting that the name of the caput was usually the same as that of the whole estate, and they could be among the earliest of place-names, often referring to a natural feature like a river. Therefore if you find a village name in early records it might actually be that of an estate or caput from which the later settlement may be descended. Some Saxon land charters also survive which can give detailed accounts of the boundaries of these and later estates.

The Viking incursions and later permanent settlement in the 9th century led to the breakup of large numbers of these estates. In order to buy loyalty or to repay service, Anglo-Saxon kings and the Viking leaders granted parts of their estates to faithful subjects, so by 1066 some English lords had gained great holdings of land. The arrival of the Normans, though, led to a virtually complete reorganisation as William the Conqueror granted these estates to

his

victorious barons, with their allocation not usually matching that of the previous English lord. These new baronies were composed of individual manors or vills, while castles and monasteries often replaced old caputs as estate centres. One element of the Saxon past which did survive was the subdivision of counties into hundreds, the boundaries of which may relate to some of the earlier large land holdings.

Alongside these changes in ownership there was a gradual conversion from an enclosed network of fields farmed mainly by family units, to one with two or three large open fields worked by a community. This change was not universal: large areas, particularly in highland England but also in parts of Essex, Kent and especially Devon, were never affected. It was also a slow process which went on developing long after the Norman Conquest, and although we know it was not introduced by the first Saxon settlers, its true origins are still elusive. In some cases an existing hamlet may have grown in size and thus necessitated the change to an open field system, or perhaps a communal decision was made to farm in this way which meant that the old settlements had to form a new central village.

Meanwhile, in the highland regions of England other great changes were occurring in the landscape. New monasteries were being founded (or

re-founded after Viking destruction) and large tracts of land were granted to them for financial support, the rents and profits from the produce paying for their grand stone buildings. During the 12th and 13th centuries, though, many monasteries found there was more profit to be made from sheep: English wool was highly valued on the Continent, and entrepreneurial monks seem to have discarded Christian ethics for a new business doctrine. They cleared their lands and in some cases whole villages, replacing them with granges (a monastic farm) from which great flocks of sheep were managed. Many of our present-day villages were created for or by the dispossessed peasants in this period of upland clearances.

The remainder of the land, be it meadows, heaths, wastes or commons, was used to graze livestock or for its material resources. Woodland was essential as timber was the principal material for building, fencing and heating. It was carefully managed and the right to cut down trees could be strictly controlled. Meadows were another important area, usually along the banks of rivers where flooding would enrich the soil. They would have been divided up into doles or strips so peasants would share the crop of hay, and then let their animals out to graze. This was becoming more important as the pressure of a rising population, which desperately needed more land under the plough, meant that there were increasing numbers of animals needing larger quantities of feed. This boom time in agriculture even forced

peasants to farm upland areas like Dartmoor and the Pennines which had not seen the plough since the Bronze Age and never have since.

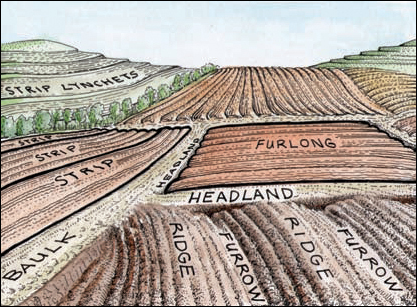

FIG 2.3:

A diagram showing the breakdown and features of the open field system. It relied upon co-operation within the community centred on the village, usually with two or three great fields, each of which would have been subdivided into furlongs, and then broken down into individual strips which were tenanted by peasant farmers. They would hold a number of them scattered around the fields. The community as a whole would meet and decide the crops to be grown in which field and when. As the fields were open, disputes between farmers over boundaries were common. There were also further complications due to inheritance which in some places meant holdings were passed onto the eldest male descendant, but in others were split between all the sons leading to ever more complex and fluctuating divisions. Also, as the population grew, more land was required to go under the plough and new fields were cut into the surrounding wastes and woodland (assarting). Sometimes these extensions were later incorporated into the existing field system, hence complicating the original arrangement

.