The Essential Book of Fermentation

Read The Essential Book of Fermentation Online

Authors: Jeff Cox

Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

USA

•

Canada

•

UK

•

Ireland

•

Australia

•

New Zealand

•

India

•

South Africa

•

China Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England For more information about the Penguin Group visit penguin.com Copyright © 2013 by Jeff Cox All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Published simultaneously in Canada Most Avery books are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchase for sales promotions, premiums, fund-raising, and educational needs. Special books or book excerpts also can be created to fit specific needs. For details, write Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Special Markets, 375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cox, Jeff, date.

The essential book of fermentation : great taste and good health with probiotic foods / Jeff Cox.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-101609071

1. Fermentation. 2. Fermented foods. 3. Probiotics. I. Title.

QR151.C65 2013 2013009623

572'.49—dc23

The recipes contained in this book are to be followed exactly as written. The publisher is not responsible for your specific health or allergy needs that may require medical supervision. The publisher is not responsible for any adverse reactions to the recipes contained in this book.

Neither the publisher nor the author is engaged in rendering professional advice or services to the individual reader. The ideas, procedures, and suggestions contained in this book are not intended as a substitute for consulting with your physician. All matters regarding your health require medical supervision. Neither the author nor the publisher shall be liable or responsible for any loss or damage allegedly arising from any information or suggestion in this book.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

For Elizabeth, Allison, Sean, Isis, and Aria

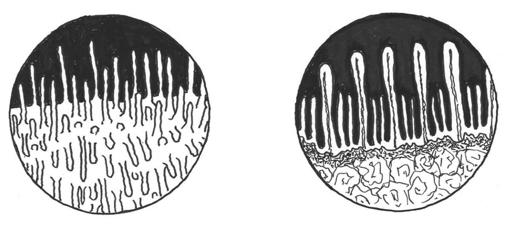

Plant root hairs (left) and intestinal villi (right) have a large surface area that greatly increases nutrient absorption capacity from the soil and intestinal contents, respectively.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface: An Epiphany About Health

Introduction

The What and Why of Fermentation

CHAPTER 1

Fermentation—The Engine of Life

CHAPTER 2

Fermented Foods as Probiotics

CHAPTER 3

Probiotics and Genetic Engineering

CHAPTER 4

The Conglomerate Superorganism

CHAPTER 5

New Findings About the Ecosystems Within Us

CHAPTER 6

The Intelligent Intestine

CHAPTER 7

A Day Spent in Berkeley with the Fermenters

A Fine Meal of Bread, Cheese, and Wine

CHAPTER 8

Bread

CHAPTER 9

Cheese

CHAPTER 10

Wine

The Recipes

CHAPTER 11

The Dairy Ferments

CHAPTER 12

The Vegetable Ferments

CHAPTER 13

The Grain and Flour Ferments

CHAPTER 14

The Bean and Seed Ferments

CHAPTER 15

Fermented Beverages

Resources

References

Index

Preface: An Epiphany About Health

One day, a scientific paper crossed my desk at

Organic Gardening

magazine describing how certain plots of land produced scabby potatoes—caused by a soil-borne fungus—while other fields were scab-free. In an experiment, soil from the healthy field was mixed into the scab-producing soil, and that immediately cured the problem. The reason, the scientists reported, was that a strong mix of microorganisms in the healthy soil literally ate up the fungus that produced scab. In the soil, it turns out, possession is nine-tenths of the law, and soils colonized by overwhelmingly large numbers of beneficial bacteria and other good microbes just don’t leave much room for disease-causing organisms to get a toehold.

Not only that, but I discovered that a wide range of soil microorganisms inhibit or kill other microbes—especially pathogenic ones that cause rot and disease in plants. This piqued my interest because it was fungus control naturally, without chemical fungicides, and fit right in with the organic method. At the same time, I was teaching myself soil science by reading Nyle Brady’s standard textbook on the subject,

The Nature and Properties of Soils.

Brady was writing about how soil microbes are intimately involved in the decomposition of organic matter. “In addition to their direct attack on plant tissue, they are active within the digestive tracts of some animals,” he wrote.

Well, sure, I thought. Fruits and vegetables, green leaves, nuts, and other organic matter are not only digested by the microbes in the compost pile and in the soil, but also by the microorganisms that inhabit every healthy human intestine and actually are ubiquitous all over the planet. In fact, all the plants and animals in the world weigh about the same as the world’s total microbial biomass. I did some further reading on the subject and was astonished to find that nine out of every ten cells in our bodies are intestinal microorganisms, and that those cells contain 99 percent of the DNA in our bodies. They live in our gut and decompose organic matter exactly the same way they do in the compost pile. When scientists looked at a healthy human intestinal flora, they found more than four hundred species of bacteria, thirty to forty of which compose about 99 percent of the flora. (Now we know that every gram of our intestinal contents contains somewhere in the neighborhood of a trillion bacteria, and that the gastrointestinal tract is the most densely colonized region of the human body.)

Longtime organic gardeners know that good, healthy compost contains similar numbers of microorganisms in each spoonful, and that rich organic soil is even more diverse than our gut bacteria, with somewhere in the neighborhood of ten thousand species of microbes. By one estimate, there may be 150 million species of microbes in the world, almost all as yet unclassified. These myriad bacteria and fungi are at the very root of health—of the soil, of plants, and of animal and human health. Maybe, I thought, a healthy mix of the proper intestinal microorganisms builds our natural good health the way it does in the soil.

This was an exciting idea. I found out several things that supported it. Our intestinal flora is indeed a source of good health. Intestinal bacteria such as

Lactobacillus acidophilus

not only decompose our food, rendering it into forms our intestines can absorb to feed our bodies, but in doing so they themselves actually manufacture vitamins such as vitamin K and many of the B vitamins—including B

12

. Further, they thrive in the acid conditions of our digestive tract, hence their species name (

acidophilus

means “acid-loving”). Disease-causing organisms prefer pH neutral conditions and have a hard time getting established in acid conditions. I asked a nutritional researcher which foods most strongly promote the establishment of a healthy intestinal flora, and he said, “If half your diet is fresh, raw fruits and vegetables, the other half can be Twinkies and you’ll be healthy.” In other words, the same thing that supports the proper nutrition of plants—actively decaying organic matter—is the same thing that supports the proper nutrition of human beings.