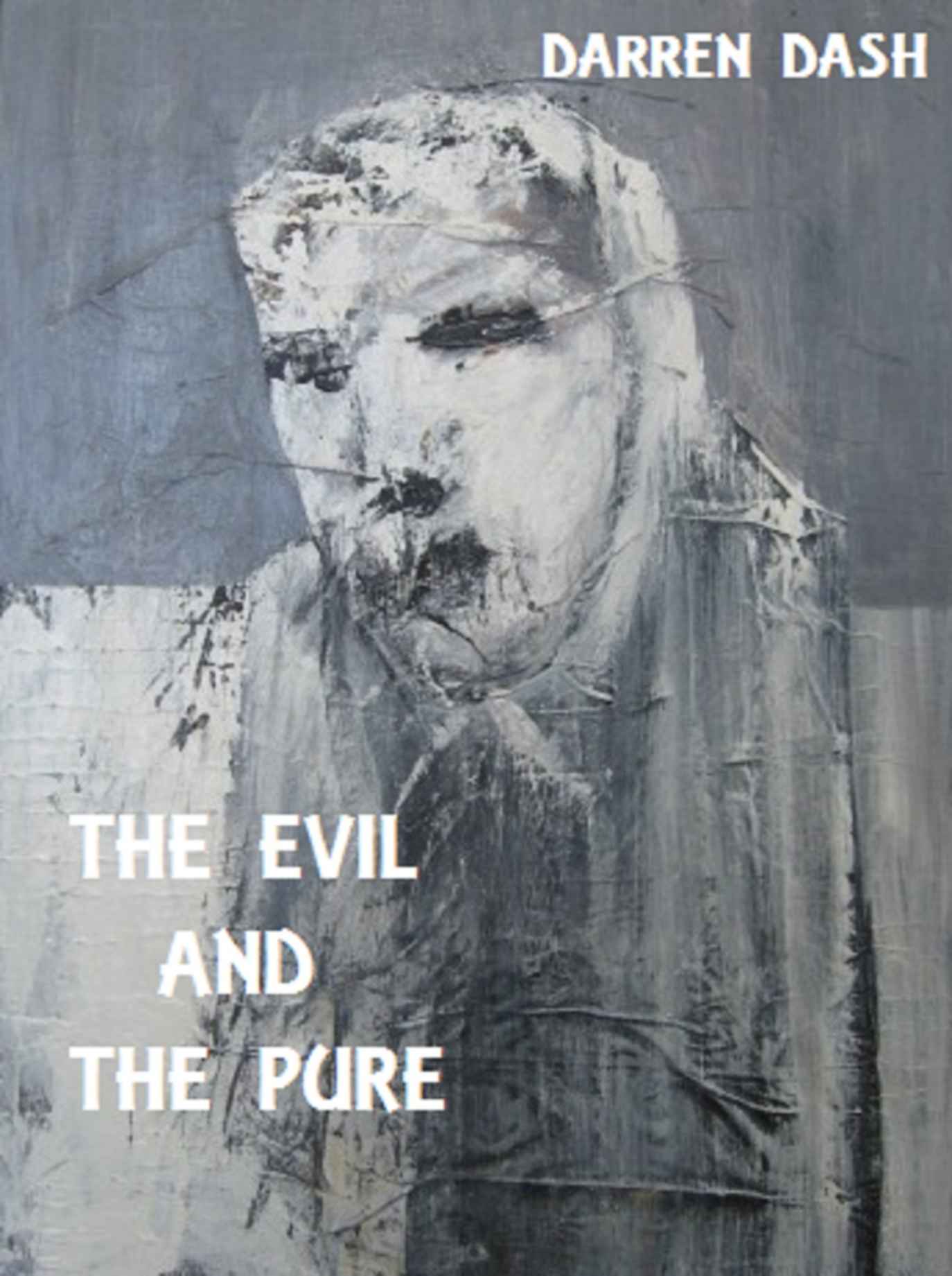

The Evil And The Pure

Read The Evil And The Pure Online

Authors: Darren Dash

The Evil And The Pure

by Darren Dash

Copyright © 2014 by Home Of The Damned Ltd

Cover painting ©

Stephen Toomey

First published in an electronic edition by Home Of The Damned Ltd February 1

st

2014

The right of Darren Dash to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead is purely coincidental.

THE EVIL AND THE PURE

in the beginning

Tulip sat in the room with the corpse and stared at the ceiling, dry-eyed.

She’d wept when she woke and

wandered in from her bedroom to find her father lying close to the window, doubled over, eyes open, impossibly still. Throwing herself down beside him, she’d called his name, hugged him, tried to shake life back into his cooling form.

She wasn’t sure how long she had held him, tears streaming down her face, oblivious to everything else. All she could recall now was moaning “Daddy,” over and over, head buried in his chest so that she didn’t have to look up into that dreadful

stiff mask of his face.

Eventually the tears ceased. She didn’t releas

e him for a long time. There was no rush. Once she stood and made the phone call, control would pass to her brother and she would become a bystander, a thirteen year old girl (“Almost fourteen,” she automatically murmured internally, as she had been doing for some months now) who would be expected to wail and mourn but play no more of an active role than that.

When she felt ready, she pushed herself back and smiled sadly at her father. She touched his lips with trembling fingers. “Daddy,” she said softly. “I love you.”

She almost broke down again, imagining him blinking and replying, not really dead (as she knew he must be), merely comatose, emerging out of his daze to call her name and wrap his arms around her and tell her that he loved her too.

But she staved off the tears. She had always been a practical girl, maybe a result of losing her mother at such a young age.

She didn’t think this loss would hit her as hard – nothing could be as hard for a little girl as having to face the death of your mother – but it had come as more of a shock. There had been lots of warning with her mum, maybe too much warning, all those months that she had fought the cancer, when they’d lived in a fog of desperate hope.

Her father, on the other hand, had seemed f

ine the night before when she’d gone to bed without kissing him, having stopped doing that a year or more ago. He had been a normal, healthy man as far as she was aware. There had been no talk of problems or illness. She was sure that he had been taken by surprise, that he hadn’t anticipated this sudden collapse. He would have talked about it with her if he’d had even a notion. Death was something they had learnt to deal with together. He wouldn’t have been afraid to discuss it with her.

She poured herself a drink, a tall glass of milk, and drank a third of it before calling Kevin and breaking the news to him. Her voice wavered as she told him that

Dad was dead, that she’d come into the living room this morning to find him sprawled lifelessly on the floor. But she didn’t cry, even when Kevin asked if she was sure, in a tone that suggested he didn’t believe she was old enough to make such a terminal call.

Kevin was at work but he told her he’d come immediately

and be with her as quickly as he could. He asked if she needed anything, if she wanted him to ring one of their neighbours or the police. She told him she was OK, she didn’t mind waiting for him by herself. He suggested she go to a local park or café, but again she said that she was fine.

She did a bit of tidying up, cleaning her room, giving the surfaces in the kitchen a wipe, keeping busy so that she didn’t have to think too much about her dead father and how her life was going to change. But her heart wasn’t in it and in the end she returned to the living room and sat in her daddy’s chair.

She stared at the corpse for a while, then fixed her gaze on the ceiling and tried to let her brain shut down. She wished humans had a standby mode, like computers, so that she could simply blank out.

It felt like hours before she heard Kevin inserting his key into the lock and pushing open the front door, but she knew it was far less than that. Her mind was playing tricks on her, that was all.

“Hey,” he panted as he stepped inside, as if he’d run to get here.

“Hey,” Tulip replied softly.

Kevin crossed the room and stopped in front of their motionless father. She heard him gulp and thought he was going to cry. That brought fresh tears to her eyes, but they hovered in the corners, not flowing yet.

“Dad,” Kevin moaned, bending to check, to make sure. He searched for a pulse, rolled one of the eyelids all the way up, opened the dead man’s l

ips and peered inside. Tulip watched with morbid fascination. She had never seen anything like this before. She wanted to know what Kevin was looking for, how to decipher the signs that would confirm for certain that they were orphans now. But she didn’t ask. She couldn’t. She had choked up and knew that she would burst into tears as soon as she tried to speak.

Kevin let out a long, shuddering breath, then turned. He wasn’t crying but he wasn’t far from it. He smiled shakily, hopelessly, and held out his arms to her.

It was what Tulip had been hoping for, and with a heartbreaking cry she hurled herself forward into his embrace, wanting him to wrap her up into a small, shivering bundle and take all of her pain and fears away. The tears came now, full force, but she didn’t care and she didn’t try to hold them back. This was a time for crying, and though it seemed hard to credit, she knew that it would pass, as it had when they’d lost their mother. Kevin was here now. He would handle all of the difficult decisions and calm and soothe her. With his guiding hand she would pull through. He’d be her guardian, her pillar, her friend and mentor. She could trust him completely and he would steer her through the awful days, weeks and months ahead. There was no escaping the pain that must be endured, but with Kevin’s help she would find a way to deal with it and move on. He would look out for her and be her rock every slow, stuttering step of the way.

After all, t

hat was a loving big brother’s job.

THE EVIL AND THE PURE

september 2000

ONE

Big Sandy lay

buried beneath a mound of newspapers, XXXL cap pulled down over his eyebrows, a third-full bottle of cheap scotch in his lap, sprawled across the floor of an alley, watching soft yellow light through a chink in the curtains of a child’s room in a house across the way. His jumper was filthy and it stank. His trousers were stained with liquor and piss. Old, scuffed boots. His fingers twitched by his sides. His feet jolted sporadically. Every now and then he mumbled to himself, grunted, cursed.

Foot traffic was sparse,

the occasional local from a nearby council estate. They passed him with no more than a glance, noses wrinkling. Most steered clear in case he made a lurch for them. Braver souls stepped over him indifferently. One woman paused, bent and dropped a pound coin in his lap. Big Sandy muttered a weak thank you and saluted drunkenly, smiling loosely. When the woman was gone he sniffed, pocketed the coin and fixed his sights on the chink in the curtains again, waiting for the light to dim.

Finally the light

in the room turned a darker yellow, hit black, came up again slightly and stopped. Just enough light for its five-year-old resident to negotiate by if he woke in the night. A shadow flickered as an adult exited, leaving the boy alone.

Big Sandy

made sure no one was present then checked his watch — twenty past seven. He didn’t look drunk any more. The tremors were gone from his feet and hands. He pushed the cap back. His eyes were dark grey, hard, focused.

He

stretched beneath the newspapers and scratched an itch. He didn’t rise. Not yet. The boy was confined to his room but his mother had the run of the house. Big Sandy didn’t want to make his move while she was there. Sarah Utah was taking a night course in computer programming. Her class started at eight. She shouldn’t be in the way much longer.

On cue, the

back door opened and Sarah emerged, late twenties, a brassy, good-looking black woman, dressed in jeans and a loose shirt. She shouted something at her husband – Big Sandy heard a muffled reply – then grabbed a bag from a table to the left of the door and set off, a bounce in her step, eager to make her class.

Big Sandy gave it ten min

utes then rose like a mountain. He shed newspapers, took off his cap, ran a hand through his lank, sandy hair, scowled at the stench of his borrowed clothes, then went to kill Tommy Utah.

He

slipped on a pair of light gloves and tested the door — locked. But the window to the right wasn’t latched. Careless. Tommy Utah all over.

Big Sandy slid the window

open. It was a tight squeeze – Big Sandy six-foot-six, built like a wrestler – but he sucked in his gut and forced himself through into Tommy Utah’s office. Lots of highbrow books on the shelves — Shakespeare, Dickens, a gulag load of Russians. Tommy Utah an educated man. That was his problem. He’d decided he was smarter than Dave Bushinsky, that he could rip off the Bush without anyone realising. Big Sandy was here to show Tommy Utah what happened when educated people tried to outsmart his boss.

Three giant strides took Big Sandy to the door.

He pressed an ear against it. No sounds outside. With a massive paw he opened the door and stepped into the corridor. Concealed on his person was a hunting knife, an untraceable handgun, knuckle-dusters, a short iron club. He didn’t think he’d need any weapons – he planned to kill Tommy Utah with his gloved hands – but it was best to come prepared.

The corridor

was deserted. Music played softly somewhere. Two lights broke the gloom of the upstairs landing, the dim yellow light from the boy’s room and a stronger light from the other end of the house. Big Sandy moved forward to climb the stairs, then stopped. The steps were uncarpeted. He snarled with disgust. Tommy Utah would have to be deaf not to hear a man of Big Sandy’s size coming up.

Big Sandy checked his watch again

— seven fifty-two. Sarah Utah’s class lasted an hour. A twenty minute walk. But it might finish early. Somebody might give her a lift home. To be safe, he had to be out of here by nine. If she walked in on him, he’d be forced to kill her too. That wasn’t part of the plan. Business was business. Tommy Utah had this coming. But Big Sandy didn’t kill innocent women. Not if he could help it.

He’d give it f

orty-five minutes. Wait for his mark to come down. If he didn’t, Big Sandy would storm up the stairs and strike quickly. Noisy, dangerous, clumsy, but Tommy Utah had to die tonight. The Bush wouldn’t tolerate a delay. Withdrawing into the shadows at the side of the stairs, Big Sandy waited.

A quarter of an hour

later, a door creaked. A shadow passed on the landing and another door creaked — Tommy Utah checking on his son. Big Sandy waited neutrally, asking nothing of the fates. When he was younger, he thought he could influence the actions of men by concentrating his will and forcing his desires upon the world. Time had taught him that he couldn’t make himself the centre of the universe just by wishing it so.

Foo

tsteps at the top of the stairs. Tommy Utah coming down. Big Sandy lowered his head and sucked in his gut, trying to appear smaller, eager not to give his position away, not to have to chase his prey up the stairs, making noise which might wake the child.