Read The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt Online

Authors: T. J. Stiles

Tags: #United States, #Transportation, #Biography, #Business, #Steamboats, #Railroads, #Entrepreneurship, #Millionaires, #Ships & Shipbuilding, #Businessmen, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous, #History, #Business & Economics, #19th Century

The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt (47 page)

Vanderbilt's discovery of this treachery provided the context for what is said to be one of the most famous letters in the history of American business: “Gentlemen: You have undertaken to cheat me. I won't sue, for the law is too slow. I'll ruin you. Yours truly, Cornelius Vanderbilt.” This terse, belligerent note is pure Vanderbilt. It is also mythology. It first appeared decades later, in Vanderbilt's obituary in the

Times

, and its validity is dubious at best. He never wrote “Yours truly,” but usually he signed, “Your obedient servant.” And it never would have occurred to him to give up legal redress. He had been suing his opponents since 1816; he knew that, even when the courts did not give satisfaction, legal action gave him leverage in negotiations.

44

But reply he did. As soon as he had wobbled on his sea legs into his office, he ordered Lambert Wardell to pull out pen and paper; he wanted to dictate a letter to James Gordon Bennett, editor of the

Herald

. “The statement made in the name of the company,” he wrote, “calls for a few words of explanation. To say nothing of the cowardice which, in my absence in a foreign country, dictated the calumnious statement referred to, it is none the less unfortunate that it was utterly false.”

Cowardice and mendacity—the two cardinal sins in Vanderbilt's business code, and the two salient traits of Joseph White—drove him into a fury. He did not owe the Transit Company, he said; rather, it owed

him

some $36,000 for property (mostly coal and coal hulks) that he had sold along with the steamships, an amount that was to have been paid out of the first earnings of the ships. “My object in accepting the agency of the steamships… was chiefly to enable me to secure the amount of the company's unpaid indebtedness to me,” he explained. “These earnings should come directly into my hands. I need not say that I would not have trusted the company for so large a sum of money upon any other terms.” His man in New York, Moses Maynard, had made the books freely available for inspection at any time. And, far from decrying lawsuits, he concluded with this warning: “My rights against the company will be determined in due time by the judgment of the legal tribunals.”

45

On September 29, the day after the

Herald

published Vanderbilt's angry letter, the Commodore and Charles Morgan met to discuss their conflict. Where they spoke is unknown, though Morgan's office was at 2 Bowling Green, only a few doors from Vanderbilt's. The Commodore proposed to refer the dispute to arbitration. Morgan seems to have thought well of the idea, but he declined to make a commitment, and the meeting broke up without any settlement.

A split seems to have formed in Accessory Transit over how to proceed. On October 27, the

Herald

reported that it had agreed to arbitration; on the next day, the company refused, making petty excuses about the state of the accounts Vanderbilt had rendered. Indeed, it taunted him, in what sounds very much like the voice of Joseph White. “The company are desirous he should commence proceedings against them at once,” said the official statement, “and are afraid he will do nothing but threaten.” Vanderbilt's lawsuit, postponed to allow time for negotiations, would proceed.

46

THE BATTLE SEEMED TO

energize Vanderbilt, for he simultaneously embarked on a series of breathtakingly huge financial transactions. First, his friend Robert Schuyler—now president of the New York & New Haven, the Illinois Central, and other railroads—asked for help. He had overextended himself in his vast stock operations, and the

Independence

, the ship he and his brother George had purchased from Vanderbilt, had sunk in the Pacific. He needed money, a lot of money; fortunately, he could offer thousands of railroad shares as collateral. Vanderbilt took them, loaning Schuyler $600,000 in October to see him through his difficulties. This was a staggering figure: if a merchant's entire estate amounted to that sum, he would be praised as extremely wealthy by the Mercantile Agency

47

Next came a fresh campaign on Wall Street led by Nelson Robinson—who, it appears, could not bear to remain in retirement as long as he owned twelve thousand Erie shares, waiting to be bulled. In mid-October, Robinson won reelection to the Erie Railroad's board of directors, and took over as treasurer; he was joined by Daniel Drew, who was new to the board. The two organized a “clique” of investors to run up the price of Erie. Vanderbilt agreed to cooperate, though he demanded a bonus in the form of a discount on the stock. He purchased four thousand shares at 70 each, 2½ below the market price. (How Robinson and Drew arranged the discount is unclear.) “The removal of so much stock, even temporarily from the market, was calculated to improve it [the price],” the

New York Evening Post

reported.

With so many stock certificates sitting in Vanderbilt's office rather than circulating among brokers, Erie's share price immediately rose. Robinson made the most of it as he worked both the curb and the trading floor on Wall Street. “His name & influence put up the price,” the Mercantile Agency reported. “It went as high as 92 in April [1854] & he sold out.” Robinson made as much as $100,000 in this single operation. Vanderbilt garnered perhaps $48,000 in profit (less brokers' commissions), in a lucrative beginning to a long and ultimately tragic relationship with Erie.

48

Success in this operation had been far from certain, but Vanderbilt “was a bold, fearless man,” Wardell later explained, “very much a speculator, understanding all risks and willing to take them.”

49

As Vanderbilt's notoriety as a speculator rose, so would the public's ambivalence toward him.

Ambivalence, but not simple loathing: the Commodore simultaneously remained the archetype of the economic hero, the productive, practical man of business, precisely the sort popularly depicted as the opposite of the speculator. Indeed, the key to understanding Vanderbilt is that he saw no distinction between the roles defined by moralists and philosophers. He freely played the competitor and monopolist, destroyer and creator, speculator and entrepreneur, according to where his interests led him. The real conundrum lies in how he saw himself. His public pronouncements reflected Jacksonian laissez-faire values, as he denounced monopolies and touted himself as a competitor. Did he detect a paradox, then, when he sold out to a monopoly or sought his own subsidies? Most likely no. Competition had arisen in America conjoined with customs and mechanisms to control it. Vanderbilt saw “opposition” as a means to an end—war to achieve a more advantageous peace. On a personal level, he was acutely aware that he had won all that he possessed by his own prowess. And whatever he won in battle, he was ready to defend in battle.

VANDERBILT'S COMBINATION

of entrepreneurship and stock market gamesmanship also appeared in his elaborate plot to take revenge on Morgan and White. The first phase involved an attempt to drive down the Accessory Transit Company's share price. He faced long odds. In December, Morgan fed information to the

New York Herald

that won him the support of its influential financial column (despite Vanderbilt's protest that the numbers leaked to the paper were “calculated to deceive”). Rumors of the company's rich profits and bright prospects sent its stock price up to 27⅝.

50

Seemingly in defiance of reality, Vanderbilt deployed a platoon of brokers on the stock exchange to sell Accessory Transit short, starting on January 5. “The bears made a dead set against it,” the

Herald

reported. Vanderbilt shorted five thousand shares—that is, sold five thousand shares that he did not own—at 25, on contracts that gave him up to twelve months to deliver the certificates. He gambled that the price would go down in the interim, so he could buy the shares for less, thus making a profit when he delivered them. “This looks like a most determined opposition,” the

Herald

noted. Morgan started buying to keep the price up, making for a direct battle between the two titans.

The next day the

New York Times

reported, “The contest of

Bull

and

Bear

opened… on Nicaragua Transit stock, [and] was followed up with considerable spirit by the buyers for the rise. The large seller yesterday it is now confidently asserted is Mr. Cornelius Vanderbilt, and the buyer Mr. Charles Morgan, the President and managing man of the Company; both old heads on the Stock Exchange, and wealthy.” The

Herald

, too, observed the “immense pressure from the bears,” as Vanderbilt's brokers sold feverishly in an attempt to drive down the share price, but “Nicaragua” stubbornly rose. “The enormous sales… had an effect quite contrary to that intended. The probability is that the same party [Vanderbilt] will not try the same game a second time. It was a desperate move, and must result in serious loss.” Now firmly on Morgan's side, the

Herald

reporter cited the “present able management” of the company and its glowing annual report, concluding that it was “rash to bear the stock.”

51

The gold coming down from the mountains led to an international rush to California. In early 1849, Vanderbilt sent his son Corneil around Cape Horn in a schooner to work on a ferry in San Francisco Bay He jumped ship, as did the gold-crazed crews of dozens of vessels, turning the San Francisco waterfront into a floating graveyard.

Library of Congress

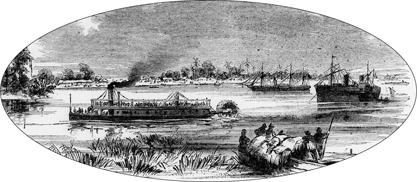

California's primary channel to the Atlantic coast consisted of steamship lines and a land crossing at Panama. Vanderbilt created a rival transit route across Nicaragua. This engraving shows a sternwheel riverboat in the harbor of Greytown on the Atlantic, having loaded passengers from a steamship in the background, as it enters the San Juan River, bound for Lake Nicaragua.

Library of Congress