The Flamingo’s Smile (15 page)

Read The Flamingo’s Smile Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

More important for American social history, Kinsey transported bodily to his sex research the radical antiessentialism of his entomological studies. Kinsey’s twenty years with

Cynips

may not be judged as a wasteful diversion compared with the later source of his fame. Rather, Kinsey’s wasp work established both the methodology and principles of reasoning that made him a pioneer in sex research.

I am not merely making learned inferences about continuities that the master of antiessentialism didn’t recognize. Kinsey knew perfectly well what he was doing. He regretted not a moment spent on wasps, both because he loved them too, and because their study had set his intellectual sights. In the first chapter of his first treatise on

Sexual Behavior in the Human Male

, Kinsey included a remarkable section on “the taxonomic approach,” with two subheadings—“in biology,” followed by the explicit transfer, “in applied and social sciences.” Kinsey wrote:

The techniques of this research have been taxonomic, in the sense in which modern biologists employ the term. It was born out of the senior author’s long-time experience with a problem in insect taxonomy. The transfer from insect to human material is not illogical, for it has been a transfer of a method that may be applied to the study of any variable population.

Extensive sampling was the hallmark of Kinsey’s work. Most earlier studies of human sexual behavior had either confined their reporting to unusual cases (Krafft-Ebing’s

Psychopathia Sexualis

, for example) or had generalized from small and homogeneous samples. If Kinsey had hoped for millions of wasps and their galls, he would at least interview many thousands of humans. He knew that he needed such large numbers because his antiessentialist perspective proclaimed two truths about variation for wasps and people alike—apparently homogeneous populations in one place (all college students at Indiana or all murderers at Alcatraz) would exhibit an enormous range of irreducible variation, and discrete local populations in different places (older middle-class women in Illinois or poor young men in New York) would differ greatly in average sexual behaviors. (Biologists refer to these two types of variation as within-population and between-population.) Kinsey decided that he would have to sample many differing groups and large numbers within each group. He wrote in the first paragraph of his treatise on males:

It is a fact-finding survey in which an attempt is made to discover what people do sexually, and what factors account for differences in sexual behavior among individuals, and among various segments of the population.

In his section on “the taxonomic approach in biology” he explained why his experience with wasps had set his methods for humans:

Modern taxonomy is the product of an increasing awareness among biologists of the uniqueness of individuals, and of the wide range of variation which may occur in any population of individuals. The taxonomist is, therefore, primarily concerned with the measurement of variation in series of individuals which stand as representatives of the species in which he is interested.

Kinsey’s belief in the primacy of variation and diversity became a crusade. His 1939 Phi Beta Kappa lecture, “Individuals,” focused on the “unlimited nonidentity” among organisms in any population and castigated both biological and social scientists for drawing general conclusions from small and relatively homogeneous samples. For example:

A mouse in a maze, today, is taken as a sample of all individuals, of all species of mice under all sorts of conditions, yesterday, today, and tomorrow. A half dozen dogs, pedigrees unknown and breeds unnamed, are reported on as “dogs”—meaning all kinds of dogs—if, indeed, the conclusions are not explicitly or at least implicitly applied to you, to your cousins, and to all other kinds and descriptions of humans…. A noted American colloid chemist startles the country with the announcement of a new cure for drug addicts; and it is not until other laboratories report failure to obtain similar results that we learn that the original experiments were based on a half dozen individuals.

As a second important transfer from his entomologically based antiessentialism, Kinsey repeatedly emphasized the impossibility of pigeonholing human sexual response by allocating people into rigidly defined categories. As his wasps formed chains of continuity from one species to the next, human sexual response could be fluid, changing, and devoid of sharp boundaries. Of male homosexuality, he wrote:

Males do not represent two discrete populations, heterosexual and homosexual. The world is not to be divided into sheep and goats. Not all things are black nor all things white. It is a fundamental of taxonomy that nature rarely deals with discrete categories. Only the human mind invents categories and tries to force facts into separate pigeon-holes. The living world is a continuum in each and every one of its aspects. The sooner we learn this concerning human sexual behavior the sooner we shall reach a sound understanding of the realities of sex.

The third transfer—the one that ultimately brought Kinsey so much trouble—raised the contentious issue of judgment. If variation is primary, copious, and irreducible, and if species have no essences, then what “natural” criterion can we discover for judgment? An odd variant is as much a member of its species as an average individual. Even if average individuals are more common than peculiar organisms, who can identify one or the other as “better”—for species have no “right” form defined by an immutable essence. Kinsey wrote in “Individuals,” again making explicit reference to wasps:

Prescriptions are merely public confessions of prescriptionists…. What is right for one individual may be wrong for the next; and what is sin and abomination to one may be a worthwhile part of the next individual’s life. The range of individual variation, in any particular case, is usually much greater than is generally understood. Some of the structural characters in my insects vary as much as twelve hundred percent. This means that populations from a single locality may contain individuals with wings 15 units in length, and other individuals with wings 175 units in length. In some of the morphologic and physiologic characters which are basic to the human behavior which I am studying, the variation is a good twelve thousand percent. And yet social forms and moral codes are prescribed as though all individuals were identical; and we pass judgments, make awards, and heap penalties without regard to the diverse difficulties involved when such different people face uniform demands.

Kinsey often claimed in his two great reports that he had merely recorded the facts of sexual behavior without either passing or even implying judgment. On the prefatory page to his report on males, he wrote:

For some time now there has been an increasing awareness among many people of the desirability of obtaining data about sex which would represent an accumulation of scientific fact completely divorced from questions of moral value and social custom.

His critics countered by arguing that an absence of judgment in the context of such extensive recording is, itself, a form of judgment. I think I would have to agree. I see no possibility for a completely “value-free” social science. Kinsey may have disclaimed in the reports themselves, but the statement just quoted from his 1939 essay makes no bones about his conviction that nonjudgmental attitudes are morally preferable—and his basic belief in the primacy of variation has evident implications itself. Can one despise what nature provides as fundamental? (One can, of course, but few people will favor an ethic that rejects life and the world as we inevitably find them.)

What, in any case, is the alternative? Should we not compile the factual data of human sexual behavior? Or should people who undertake such a study sprinkle each finding with an irrelevant assessment of its moral worth from their personal point of view? That would be hubris indeed. Ultimately, however, I must confess that my approval of Kinsey, and my strong attraction to him, arises from our shared values. I too am a taxonomist.

At the beginning of

The Grapes of Wrath

, as Tom Joad heads home after a prison term, he meets Casy, his old preacher. Casy explains that he no longer holds revivals because he could not reconcile his own sexual behavior (often inspired by the fervor of the revival meeting itself) with the content of his preaching:

I says, “Maybe it ain’t a sin. Maybe it’s just the way folks is.”…Well, I was layin’ under a tree when I figured that out, and I went to sleep. And it come night, an’ it was dark when I come to. They was a coyote squawkin’ near by. Before I knowed it, I was sayin’ out loud…“There ain’t no sin and there ain’t no virtue. There’s just stuff people do…. And some of the things folks do is nice, and some ain’t nice, but that’s as far as any man got a right to say.”

*

THROUGHOUT A LONG DECADE

of essays I have never, and for definite reasons, written about the biological subject closest to me. Yet for this, my hundredth effort, I ask your indulgence and foist upon you the Bahamian land snail

Cerion

, mainstay of my own personal research and fieldwork. I love

Cerion

with all my heart and intellect but have consciously avoided it in this forum because the line between general interest and personal passion cannot be drawn from a perspective of total immersion—the image of doting parents driving friends and neighbors to somnolent distraction with family movies comes too easily to mind. These essays must follow two unbreakable rules: I never lie to you, and I strive mightily not to bore you. But, for this one time in a hundred, I will risk the second for personal pleasure alone.

Cerion

is the most prominent land snail of West Indian islands. It ranges from the Florida Keys to the small islands of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao, just off the Venezuelan coast, but the vast majority of species inhabit two principal centers—Cuba and the Bahamas.

Cerion

’s life includes little excitement by our standards. Most species inhabit rocks and sparse vegetation abutting the seashore. They may live for five to ten years, but they spend most of this time in the warm weather equivalent of hibernation (called estivation), hanging upside down from vegetation or affixed to rocks. After a rain or sometimes in the relative cool and damp of night, they descend from their twigs and stones, nibble at the fungi on decaying vegetation, and perhaps even copulate. We have marked and mapped the movement of individual snails and many can be found on the same few square yards of turf, year after year.

Why pick

Cerion?

Why, indeed, spend so much time on any detailed particular when all the giddy generalities of evolutionary theory beg for study in a lifetime too short to manage but a few? Iconoclast that I am, I would not abandon the central wisdom of natural history from its inception—that concepts without percepts are empty (as Kant said), and that no scientist can develop an adequate “feel” for nature (that undefinable prerequisite of true understanding) without probing deeply into minute empirical details of some well-chosen group of organisms. Thus, Aristotle dissected squids and proclaimed the world’s eternity, while Darwin wrote four volumes on barnacles and one on the origin of species. America’s greatest evolutionists and natural historians, G.G. Simpson, T. Dobzhansky, and E. Mayr, began their careers as, respectively, leading experts on Mesozoic mammals, ladybird beetles, and the birds of New Guinea.

Scientists don’t immerse themselves in particulars only for the grandiose (or self-serving) reason that such studies may lead to important generalities. We do it for fun. The pure joy of discovery transcends import. And we do it for adventure and for expansion. As drama, Bahamian field trips may seem risible compared with Darwin on the

Beagle

, Bates on the Amazon, and Wallace in the Malay Archipelago—although I would not care to repeat my only close brush with death, caught in a shoot-out among drug runners on North Andros. So much more do I value the quiet times in different worlds: an evening’s discussion of bush medicine on Mayaguana, an exploration of ornamental carvings that adorn roofs on Long Island and South Andros, and the finest meal I have ever eaten—a campfire pot of fresh conch stewed with sweet potatoes from Jimmy Nixon’s garden on Inagua, after a hot and hard day’s work.

If all good naturalists must choose a group of organisms for detailed immersion, we do not select mindlessly or randomly (or even, as some cynics have suggested, because the Bahamas beat the Yukon as a field area). I am interested primarily in the evolution of form and have concentrated on how the varying shapes of an individual’s growth can serve as a source of evolutionary change (see my technical book,

Ontogeny and Phylogeny

, in bibliography). An invertebrate paleontologist with these interests would naturally be led to snails, since their shells preserve a complete record of growth from egg to adult.

A student of form with a penchant for gastropods could not avoid

Cerion

, for this genus exhibits, among its several hundred species, a range of form unmatched by any other group of snails. Some

Cerions

are tall and pencil thin; others are shaped like golf balls. When a colleague ventured “square snails” as an example of impossible animals at a public meeting, I was able to show him the peculiar quadrate

Cerion

from the photo on p. 170, bottom row, second from left. Five years ago, I discovered the largest

Cerion

, a thin and parallel-sided fossil giant from Mayaguana more than 70 mm tall. The smallest is a virtual sphere, scarcely 5 mm in diameter, from Little Inagua (see photo).

Cerion

’s mystery and special interest do not lie in its exuberant diversity alone; many groups of animals include some members with unusual propensities for speciation and consequent variation of form. Species are the fundamental units of biological diversity, distinct populations permanently isolated one from the other by an absence of interbreeding in nature. We should not be surprised that groups producing large numbers of species may become quite diverse in form, since more distinct units provide more opportunities for evolving a wide range of morphologies.

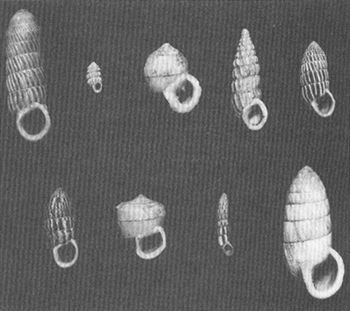

Various

Cerion

shells from the Bahamas and Cuba to show the unparalleled diversity of form within this genus.

PHOTO BY AL COLEMAN

.

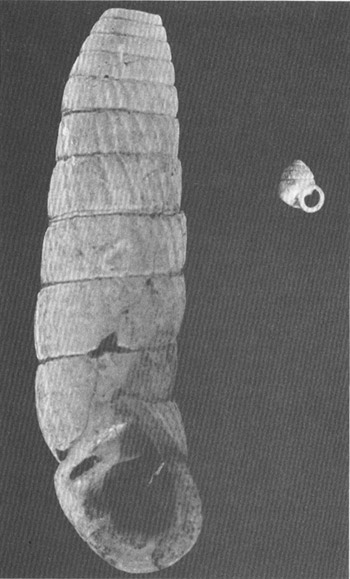

The largest and smallest known

Cerion

shells (and I mean specimens, not representatives of species). I found the giant

Cerion excelsior

on Mayaguana. The dwarf

C. baconi

lives on Little Inagua. I estimate the giant’s height (missing top restored) at over 70 mm.

PHOTO BY RON ENG

.

Faced with such a riotous array of shapes, older naturalists did name species aplenty in

Cerion

, some 600 of them. But few are biologically valid as distinct noninterbreeding populations. In ten years of fieldwork on all major Bahamian islands, we have only once found two distinct

Cerion

populations living in the same place and not interbreeding—true species, therefore. These included a giant and a dwarf—thus recalling various bad jokes about Chihuahuas and Great Danes. In all other cases, two forms, no matter how distinct in size and shape, interbreed and produce hybrids at their point of geographic contact. Somehow,

Cerion

manages to generate its unparalleled diversity of form without parceling its populations into true species. How can this happen? Moreover, if such different forms hybridize so readily, then the genetic differences between them cannot be great. How can such diversity of size and shape arise in the absence of extensive genetic change?

In a related and second mystery, distinct forms of

Cerion

often inhabit widely separated islands. The simplest explanation would propose that these far-flung colonies represent the same species and that hurricanes can blow snails great distances, producing haphazard distributions, or that colonies once inhabiting intermediate islands have become extinct, leaving large distances between survivors. Yet, all

Cerion

experts have developed the feeling (which I share) that these separated colonies, despite their detailed similarity for long lists of traits, have evolved independently

in situ

. If this unconventional interpretation is correct, how can such complex suites of associated traits evolve again and again?

Cerion

thus presents two outstanding peculiarities amidst its unparalleled diversity: Its most distinct forms interbreed and are not true species, while these same forms, for all their complexity, may have evolved several times independently. Any scientist who can explain these odd phenomena for

Cerion

will make an important contribution to the understanding of form and its evolution in general. I shall try to describe the few preliminary and faltering steps we have made towards such a resolution.

Cerion

has attracted the attention of several prominent naturalists, from Linnaeus, who named its first species in 1758, to Ernst Mayr, who pioneered the study of natural populations 200 years later. Still, despite the efforts of a tiny group of aficionados,

Cerion

has not received the renown it deserves in the light of its curious biology and its promise as an exemplar for the evolution of form. Its relative obscurity can be traced directly to past biological practice. Older naturalists buried

Cerion

’s unusual biology under such an impenetrable thicket of names (for invalid species) that colleagues interested in evolutionary theory have been unable to recover the pattern and interest from utter chaos.

The worst offender was C.J. Maynard, a fine amateur biologist who named hundreds of

Cerion

species from the 1880s through the 1920s. He imagined that he was performing a great service, proclaiming in 1889:

Conchologists may take exception to some of my new species, thinking, perhaps, that I have used too trivial characters in separating them. Believing, however, as I do, that it is the imperative duty of naturalists today, to record minute points of differences among animals…I have not hesitated so to designate them, if for no other reason than for the benefit of coming generations.

I trust that I shall not be accused of undue cynicism in recognizing another reason. Maynard financed his Bahamian trips by selling shells, and more species meant more items to flog.

Caveat emptor

.

Professional colleagues were harsh on Maynard’s overly fine splitting. H.A. Pilsbry, America’s greatest conchologist, declared in uncharacteristically forceful prose that “gods and men may well stand aghast at the naming of individual colonies from every sisal field and potato patch in the Bahamas.” W.H. Dall labeled Maynard’s efforts as “noxious and stupefying.” Yet, when tested in the crucible of practice, neither Pilsbry nor Dall lived up to his brave words. Each recognized at least half the species Maynard advocated, still sufficiently overinflated to bury any pattern in the forest of invalid names.

So rich was

Cerion

’s diversity, and so numerous its species, that G.B. Sowerby, the outstanding English conchologist, who fancied himself (with little justification) a poet, wrote this doggerel in introducing his monograph on the genus:

Things that were not, at thy command,

In perfect form before Thee stand;

And all to their Creator raise

A wondrous harmony of praise.

Sowerby then proceeded to list quite a chorus. And this quatrain dates from 1875, before Maynard ever named a

Cerion

!

In the light of this existing chaos, and before we can even ask the general questions about form that I posed above, we must pursue a much more basic and humble task. We must find out whether any pattern can be found in the ecological and geographic distribution of

Cerion

’s morphology. If we detect no correlation at all with geography or environment, then what can we explain? Fortunately, in a decade of work, we have reduced the chaos of existing names to predictable patterns and have thereby established the prerequisite for deeper explanation. Of the nature of that deeper explanation, we have intuitions and indications, but neither definite information nor even the tools to provide it (for we are stuck in an area of biology—the genetics of development—that is itself woefully undeveloped). Still, I think we have made a promising start.

I say “we” because I realized right away that I could not do this work alone. I felt competent to analyze the growth and form of shells, but I have no expertise in two areas that must be united with morphology in any comprehensive study: genetics and ecology. So I teamed up with David Woodruff, a biologist from the University of California at San Diego. For a decade we have done everything together, from blisters on Long Island to bullets on Andros.