The Food of a Younger Land (27 page)

Read The Food of a Younger Land Online

Authors: Mark Kurlansky

In every crowd there is one expert, who builds the fire, prepares the meat, lays the grill over the coals when the blaze has burned down to a tiny flicker, then places the steaks on the grill and tends them with a long handled fork as they sizzle. Loin steak, cut from one-half to three-fourths of an inch thick is used. Hungry guests often eat a half pound at a sitting. Usually tending the steaks is a man’s job. The women prepare the salad, fry the potatoes and make the coffee.

The potatoes are first boiled at home and brought out to the picnic spot in a kettle. Then they are sliced and placed in a skillet with a large dab of grease. If there is room on the grill the skillet occupies a corner and the “spuds” are allowed to fry slowly. Coffee, sometimes prepared at home and brought out in a thermos jug, is better if boiled and served fresh. In that event it is made in the old fashioned way, that is, boiled in an open kettle, the grounds in a muslin sack.

Kansas is a prohibition state where the sale of 5.2 beer is legal; beverages of higher alcoholic content are banned. If there are drinks at the steak roast they are usually poured from a bottle. The men often take their whiskey straight or with plain water, women prefer it with soda and lemon. Few of the sophisticated drinks are served, although a hostess in one of the larger cities used to mix a thermos jug full of martinis for these outdoor celebrations.

Kansans are becoming increasingly addicted to the “Cup that cheers but does not inebriate.” Most office workers go out for coffee at least twice during the day, executives frequently adjourn to the corner coffee shop for a conference over a steaming cup. Mid-morning coffee is popular even in the summer, but the afternoon recess is usually accompanied by iced tea or Coca-Cola. Few Kansans care for hot tea, but consume many glasses of the iced beverage, usually with lemon, with or without sugar. Mint leaves sometimes provide an added flavor. In comparatively recent years iced coffee has attained a degree of popularity as a hot weather beverage.

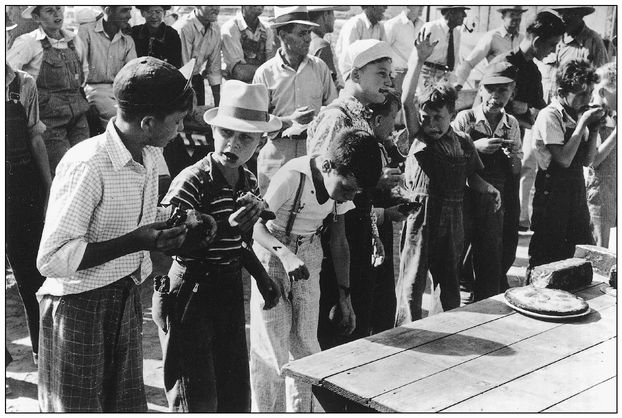

END OF THE PIE-EATING CONTEST. WINNER’S HAND IS RAISED. 4-H CLUB FAIR, CIMARRON, KANSAS. (PHOTOGRAPH BY RUSSELL LEE)

Sioux and Chippewa Food

FRANCES DENSMORE

Frances Densmore was born on May 21, 1867, in Red Wing, Minnesota, where she also died ninety years later almost to the day, on June 5, 1957. In between she was one of the distinguished American women of her generation, translating a lifelong love of music into a celebrated career in anthropology.

She began with music, studying at Oberlin College’s Conservatory of Music, after which she worked as a piano teacher in St. Paul. In 1889 she moved to Boston to study at Harvard under composers John Knowles Paine and Carl Baermann.

In 1893 she attended the Chicago World’s Fair, where she saw the great Apache leader Geronimo, and she heard him humming a tune. That tune marked the beginning of a lifelong fascination with Indian music. In 1907 she published her first anthropological writing, an article in

American Anthropologist

on a 1905 visit to a Chippewa village in Minnesota near the Canadian border. With grants from the Smithsonian, she began recording Indian music. The Smithsonian backed her work for many decades as she recorded on wax cylinders almost 2,500 songs of not only the Chippewa but the Sioux, Pawnee, Yuma, Yaqui, Cocopa, Northern Ute, and some twenty-three other tribes. She did this work at a time when most of the tribes still had rich cultures, but they were soon to fade. Her extensive collection of traditional Indian musical instruments is at the Smithsonian, which has also issued her recordings. The Smithsonian has published her numerous monographs on Indian music as well. Her two volumes on the Chippewa, published in 1910 and 1915, are considered some of her most important work.

American Anthropologist

on a 1905 visit to a Chippewa village in Minnesota near the Canadian border. With grants from the Smithsonian, she began recording Indian music. The Smithsonian backed her work for many decades as she recorded on wax cylinders almost 2,500 songs of not only the Chippewa but the Sioux, Pawnee, Yuma, Yaqui, Cocopa, Northern Ute, and some twenty-three other tribes. She did this work at a time when most of the tribes still had rich cultures, but they were soon to fade. Her extensive collection of traditional Indian musical instruments is at the Smithsonian, which has also issued her recordings. The Smithsonian has published her numerous monographs on Indian music as well. Her two volumes on the Chippewa, published in 1910 and 1915, are considered some of her most important work.

This manuscript on Chippewa and Sioux food was written by Densmore for

America Eats

and edited by the Minnesota Writers’ Project.

America Eats

and edited by the Minnesota Writers’ Project.

T

he principal food of the early Sioux was meat. In the winter they ate muskrats, badgers, otters and raccoons, in the spring they ate fish and the roots of certain wild plants, in the summer they had wild pigeons and cranes as well as fish and certain roots and in the autumn they killed wild ducks, geese and muskrats. These were animals that were plentiful at different seasons of the year. The buffalo was hunted twice a year, and the meat was eaten fresh or dried and prepared in various ways. The tongue of the buffalo was considered the nicest part. In the earliest times the Sioux boiled meat by digging a hole in the ground and lining it with a fresh hide. They put water in this, with the meat, and added stones that were heated in the fire. These heated the water, cooking the meat.

he principal food of the early Sioux was meat. In the winter they ate muskrats, badgers, otters and raccoons, in the spring they ate fish and the roots of certain wild plants, in the summer they had wild pigeons and cranes as well as fish and certain roots and in the autumn they killed wild ducks, geese and muskrats. These were animals that were plentiful at different seasons of the year. The buffalo was hunted twice a year, and the meat was eaten fresh or dried and prepared in various ways. The tongue of the buffalo was considered the nicest part. In the earliest times the Sioux boiled meat by digging a hole in the ground and lining it with a fresh hide. They put water in this, with the meat, and added stones that were heated in the fire. These heated the water, cooking the meat.

Buffalo meat was cut in strips and dried in the sun or over a fire. This was called “jerked meat” and used by many tribes living on the plains. But the favorite way of preparing buffalo meat was in the form of pemmican. For this, thin buffalo steaks were dried, then laid on a broad, flat stone and pounded with a smaller stone. In the old days, the Indians dug a hole like a large bowl in the ground and lined it with a piece of hide, fitting it neatly all around. Then they put in the dried meat and pounded it with a heavy stone. The pounded meat is like a powder with many shreds of threads or fiber in it. This was usually mixed with melted fat, but marrow made even nicer pemmican. Sometimes the Indian women pounded wild cherries, stones and all, and mixed them with the pemmican. The mixture was put in bags made of hide, and melted fat was poured on the top to seal it tightly. Buffalo hide was often used for these bags, with the hair on the outside. Pemmican was very nourishing and could be kept in the sealed bags for three or four years. The bags were of various sizes, those in common use weighing from 100 to 300 pounds.

The Sioux, like other tribes of Indians, had no salt until the traders came, and it took them a long time to learn to like it. Even in 1912 the older members of the tribe did not like the taste of salt.

Some of the Sioux who lived around the upper water of the Minnesota River had a small quantity of corn and beans, but their chief vegetable food was a root that was commonly called “Dakota turnip” or “tipsinna,” although it has several other names. This root was dug in August and was about as large as a hen’s egg. The Sioux ate it raw, or boiled it or roasted it in the ashes; they also dried it and stored it for winter. The dried root was mashed between stones until it was like flour; then mixed with water, this was made into little cakes and baked over the coals. It did not have much taste, yet it was not unpleasant to eat and was very nourishing. Two interesting travelers came to Minnesota in 1823 and mentioned this root in their description of their trip. These men were Major Stephen H. Long and Professor William H. Keating. Near Lake Traverse, they became acquainted with Chief Wanotan, who invited them to a feast. There were many large kettles and the food was emptied into “dozens of wooden dishes which were placed all around the lodge.” The food “consisted of buffalo meat boiled with tepsin, also the same vegetable boiled without meat in buffalo grease, and finally the much-esteemed dog meat, all which were dressed without salt.” The white men were polite and tasted of the dog meat. They did not enjoy eating it, but Keating wrote that it was very fat as well as “sweet and palatable” and quite dark in color. The Sioux considered it a great honor to a guest when they placed a dish of nicely cooked dog meat before him. The writer has seen this custom among both the Sioux and the Chippewa. A small dog, when cooked, looks somewhat like a platter of large chicken.

When the Sioux lived in northern Minnesota, they ate the wild rice that grows in the shallow lakes. This was a nourishing food and easy to gather.

After they learned to raise corn and beans, the work in the field was done by the women. They never planted corn until the wild strawberries were ripe. That was supposed to be exactly the right time to plant corn, and they soaked the seed corn until it sprouted before they put it in the ground. The women planted it quite deep, and when the little plants had two or three leaves the women loosened the earth around the roots with their fingers. When the plants were taller the women made the earth into a little hill around each plant, using hoes for the work. White people gave the Indians several sorts of seed corn, but they usually planted a small kind of corn that ripened quickly.

The women gathered the ripe ears of corn in their blankets and spread them on platforms or scaffolds. The women and children had to stand on the platforms to drive away the birds that came to get the corn. When the husks began to wither, they took off the outer husks and braided the rest in stiff braids as they had been taught to do by the white people. These were hung up so the corn would dry. Some of the corn was boiled, dried and put in bags that contained 1 or 2 bushels. A round hole was dug in the ground, and the bottom and sides were lined with dry grass. The bags of corn were put in the hole, which was filled with earth and firmly stamped down. Corn stored in this way is said to have kept dry and fresh from September until the next April. The hole containing the corn was covered in such a way that no one could see it, but the man who hid the corn could find it even though the ground was covered deep with snow.

The food of an Indian family depended on where the tribe lived. The Chippewa lived on the shores of Lake Superior and along the rivers, so their principal food was fish. They ate fresh fish in summer and dried or smoked fish in winter. They were satisfied in the old days if they had nothing but fish for a meal. The littlest babies were given fish soup, and the heads of fish were said to be very nice when boiled and seasoned with maple sugar.

The Chippewa had many ways of cooking fish, from the little sunfish to the large pickerel. Fresh fish were cleaned and put between the sections of a split stick that was placed in the ground, leaning over the fire. Sometimes the fish, without being cleaned, were stuck through with a sharp stick, head uppermost, and the stick slanted above the fire so that it could be turned and the fish cooked on all sides. Fish eggs were boiled or fried with the fish.

In the fall, the Chippewa strung the sunfish in bunches of 10 or 12 and froze them for winter use. When the snow was deep around the wigwam, they peeled the skin from these little fish and cooked them. Sometimes they strung small fish on strips of basswood bark and hung them in the sun to dry, then packed them in layers, without salt.

The Chippewa had no special food for children, and little children were given very strong tea and meat. It was thought that the meat would make them strong.

Maple sugar was used to sweeten and season all food. Like the Sioux, these Indians had no salt until it was brought by the white men, but they learned to like it. In a treaty made with the Chippewa in 1847, the government promised to give them five barrels of salt every year for five years. This is known as the “Salt Treaty.”

Ducks, wild pigeons and other birds came in the fall, and the Chippewa cooked them in various ways. Sometimes they cooked little birds in hot ashes without removing the feathers, and sometimes they put a sharp stick through the bird, after removing the feathers, and put the stick upright in front of the fire. They also boiled birds with rice, potatoes and meat.

The deer was the principal game hunted by the Chippewa, though they also killed mouse, bear, rabbits and other animals at various seasons. Beaver tails were considered a great luxury because they were so fat. Fresh venison was sometimes boiled with wild rice and sometimes cut in thin slices, roasted and then pounded on a flat stone. Then it was stored in boxes,

ma-kuks

, and the covers sewed down with split spruce root. If the deer was killed in the fall, they cut a portion of the meat in strips, dried it over a fire and wrapped it in the hide. In the winter they boiled this meat or prepared it in other ways. Sometimes they cut the dried meat in pieces, spread it on birchbark and covered it with another piece of the bark. A man then stamped heavily on the upper piece of bark until the meat was crushed. Meat prepared this way was called by a name meaning “foot-trodden meat.”

ma-kuks

, and the covers sewed down with split spruce root. If the deer was killed in the fall, they cut a portion of the meat in strips, dried it over a fire and wrapped it in the hide. In the winter they boiled this meat or prepared it in other ways. Sometimes they cut the dried meat in pieces, spread it on birchbark and covered it with another piece of the bark. A man then stamped heavily on the upper piece of bark until the meat was crushed. Meat prepared this way was called by a name meaning “foot-trodden meat.”

If a deer was killed during the winter, they dried the meat enough so that it would keep until spring. Then they put it in the sun to finish drying.

After the Chippewa had driven the Sioux out of northern Minnesota, they had plenty of wild rice. Here, as in Wisconsin, were quantities of strawberries, blueberries, cranberries, wild plums and cherries, as well as other fruits. They had several recipes for cooking acorns and dug certain roots commonly called “Indian potatoes.” In the spring they made maple sugar and syrup, and in early summer they planted corn, pumpkins and squash. We do not know how much gardening they learned from early white traders and settlers but they made gardens many years ago.

It is said that the Chippewa women were very good cooks and knew how to use all sorts of seasonings, though they had no pepper nor salt. They used wild ginger a great deal in seasoning meat and other food. They made tea out of wintergreen or raspberry leaves, or little twigs of spruce, and in summer they made a refreshing drink by putting a little maple sugar in a cup of cold water.

Other books

The Foremost Good Fortune by Susan Conley

The Barber Surgeon's Hairshirt (Barney Thomson series) by Lindsay, Douglas

Dark Lycan by Christine Feehan

Taste of Lightning by Kate Constable

Oh Danny Boy by Rhys Bowen

Stories From Candyland by Candy Spelling

The Glimpses of the Moon by Edmund Crispin

Essays After Eighty by Hall, Donald

SeducingtheHuntress by Mel Teshco

MadameFrankie by Stanley Bennett Clay