The Food of a Younger Land (31 page)

Read The Food of a Younger Land Online

Authors: Mark Kurlansky

LEFSA

2 qts. hot boiled potatoes

2 tbsp. lard

½ cup sweet cream

1 heaping tbsp. salt

Flour

2 tbsp. lard

½ cup sweet cream

1 heaping tbsp. salt

Flour

Mash potatoes thoroughly. Cool. Heat lard and cream; add to cold potatoes. Knead in sufficient flour to roll very thin. Bake on top of stove.

NORWEGIAN MEAT BALLS2 lbs. ground beef

½ tsp. pepper

1 cup bread crumbs

¼ tsp. nutmeg

2 eggs, beaten

1 small onion, chopped

3 tsp. salt

1 cup milk

½ tsp. pepper

1 cup bread crumbs

¼ tsp. nutmeg

2 eggs, beaten

1 small onion, chopped

3 tsp. salt

1 cup milk

Mix hamburger, bread crumbs, and seasonings. Add beaten eggs. Add milk, gradually, kneading well. Cool overnight. Roll into balls and fry. Remove meat balls from skillet; make gravy by browning flour, and adding equal parts of milk and water. Season to taste. Return meat balls to gravy; place in slow oven for about an hour.

FATTIGMAND10 egg yolks

8 egg whites

1 cup sugar

1 cup whipping cream

1½ tbsp. melted butter

Enough flour to roll out

2 tsp. cardamom

8 egg whites

1 cup sugar

1 cup whipping cream

1½ tbsp. melted butter

Enough flour to roll out

2 tsp. cardamom

Beat egg whites and yolks with sugar for 20 minutes. Add cream, melted butter, and other ingredients. Roll thin; cut in diamonds, and fry in deep fat.

LUTEFISKDry codfish

Water

Lye

Water

Lye

The preparation of lutefisk by this method requires only fifteen days. Place the dry codfish in clean, cold water and let stand one week, changing water every morning. Then make lye solution; 1 tsp. lye to each 4 or 5 pounds of fish. Don’t have the solution too strong, lest the fish soften too rapidly. Let stand four days, keeping in a cold place. Then pour off the lye solution and cover with clear, cold water. Soak another 4 days, changing water each morning, and continuing to keep in a cold place.

When ready to cook, take the amount to be used and place in a cloth bag. Place in kettle and pour boiling water over it. Boil gently 5 to 10 minutes, until done. Add salt to taste. Carefully drain, skin, and bone. Put on a platter and serve with brown melted butter or cream sauce.

Indiana Pork Cake

FROM HAZEL M. NIXON, 40 NORTH GALESTON STREET, INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA

1 pound of ground or finely chopped pork

1 cup of boiling water poured over pork

1 cup of molasses

2 cups of brown sugar

1 teaspoonful of soda

Stir in 1 pound of raisins, 1 pound of chopped dates (latter

not necessary) and ½ pound of finely chopped citron

Add 4 cups of flour

1 teaspoonful of cloves

1 teaspoonful of cinnamon

1 teaspoonful of allspice

1 teaspoonful of nutmeg

1 cup of boiling water poured over pork

1 cup of molasses

2 cups of brown sugar

1 teaspoonful of soda

Stir in 1 pound of raisins, 1 pound of chopped dates (latter

not necessary) and ½ pound of finely chopped citron

Add 4 cups of flour

1 teaspoonful of cloves

1 teaspoonful of cinnamon

1 teaspoonful of allspice

1 teaspoonful of nutmeg

Pork must be fresh and raw; fat preferred. Will keep two or three months, if wrapped in greased paper, then in dry paper. Don’t bake too quickly.

Nebraska Lamb and Pig Fries

H. J. MOSS

O

ften referred to as mountain oysters, lamb and pig fries are a much dramatized special food event. Being distinctly male in character it is associated more or less with stag parties or mere man get-to-gethers. Somehow the ladies just don’t seem to fit into such affairs. Still they are sometimes present and take a keen interest in the menu, which of course is principally what the title of the banquet implies. Groups, such as the American Legion, hunting clubs, gun clubs, and so forth, go in for this sort of thing in Nebraska in a big way. Little publicity is necessary so the general public hears very little about such banquets or feeds.

ften referred to as mountain oysters, lamb and pig fries are a much dramatized special food event. Being distinctly male in character it is associated more or less with stag parties or mere man get-to-gethers. Somehow the ladies just don’t seem to fit into such affairs. Still they are sometimes present and take a keen interest in the menu, which of course is principally what the title of the banquet implies. Groups, such as the American Legion, hunting clubs, gun clubs, and so forth, go in for this sort of thing in Nebraska in a big way. Little publicity is necessary so the general public hears very little about such banquets or feeds.

Beer (or stronger) drinking is associated with these affairs and is probably the rule instead of the exception. Since the average lady cook has very little experience in cooking pig or lamb fries, a man cook, better versed, usually officiates at the stove. The fries are generally dipped in egg-batter and cracker crumbs and dropped into very hot, deep fat. Ordinarily most epicures like their fries done to a crisp. Rare fries are not looked upon with favor.

Fries are one article of food which seldom finds its way to the family table. It is definitely limited to male group meetings and is the theme of the entire program and the reason for its existence. It provides a subtle atmosphere of the carnal and unusual and its very character enhances the occasion in a sort of “forbidden fruit” or “a little of the devil” way.

These fries are quite popular in Nebraska and are more deliberate than they are spontaneous, since advance arrangements usually have to be made—the item generally not being available in the open market. Docking pigs and lambs is a sort of community activity and farmers often take advantage of the occasion to hold a fry as a fitting sequel to the activity itself. This food item is particularly rich and those who overeat are quite apt to be deviled with a splitting headache the following day, which malady often is blamed to the overindulgence in other refreshments more liquid in form.

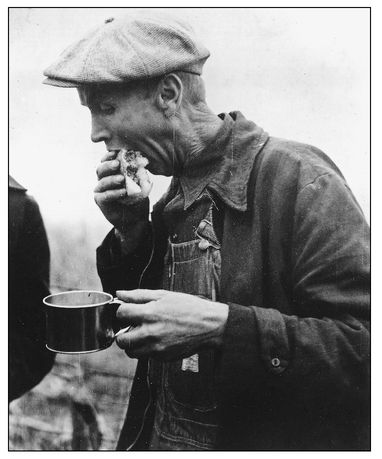

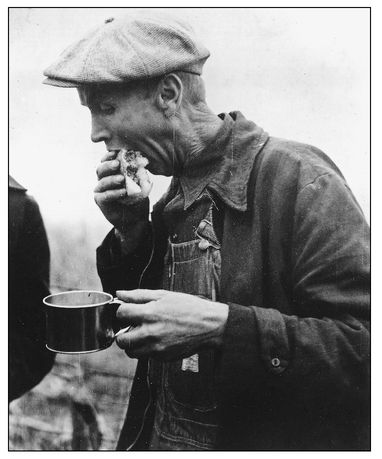

FARMER EATS HAMBURGER AT CORN-HUSKING CONTEST, MARSHALL COUNTY, IOWA . (PHOTOGRAPH BY ARTHUR ROTHSTEIN)

Kansas Beef Tour

WILLIAM LINDSAY WHITE

The reference to “Young Bill White” was because at this time he was largely known as the son of the newspaper editor William Allen White. Many of the people in Emporia, Kansas, thought that the younger Bill, William Lindsay White, was a bit too uppity. It was not just that he went to Harvard, but while there his Kansas accent seemed to have been replaced by something vaguely English that went with his new habit of wearing a monocle. For a time he was listed as one of the best-dressed men in America. His wife, Katherine, a friend of Bernard Baruch, Claire Booth Luce, and John O’Hara, was what was called in Emporia “a New York sophisticate.” Baruch wrote that she was the most beautiful woman in New York. The Whites lived part-time in Kansas and part-time in their New York brownstone. White was a prominent war correspondent and worked with the legendary Edward R. Murrow at CBS. He wrote a number of successful books on World War II that were picked up by Hollywood, the most well known of which was the 1942 bestseller

They Were Expendable

.

They Were Expendable

.

But in 1944 his ailing father persuaded him to return to Kansas and take over the post of editor of the

Emporia Gazette

, from which position he opposed urban renewal and championed Republican politicians. He played an important role in the launching of the career of U.S. Senator Bob Dole and was a friend and supporter of Richard Nixon. By coincidence, White died in 1973, at the height of his friend’s Water-gate scandal.

Emporia Gazette

, from which position he opposed urban renewal and championed Republican politicians. He played an important role in the launching of the career of U.S. Senator Bob Dole and was a friend and supporter of Richard Nixon. By coincidence, White died in 1973, at the height of his friend’s Water-gate scandal.

T

he Lyon County Beef Tour and Barbecue, which has become an important annual event in the Flint Hills during the past few years, is described by W. L. “Young Bill” White, whose comments on the art of barbecue and other traditional dishes of the range will be interesting to the editors.

he Lyon County Beef Tour and Barbecue, which has become an important annual event in the Flint Hills during the past few years, is described by W. L. “Young Bill” White, whose comments on the art of barbecue and other traditional dishes of the range will be interesting to the editors.

“The Beef Tour is a regular event in this part of the world, the annual feast day of the cow country. It is under the auspices of the county agent and this year there were several visiting dignitaries from the State Agricultural college and from the Department of Agriculture in Washington.

“It takes a whole day, and is routed through the best farms and ranches. At each stop the visitors range their cars in a huge half moon and stay in their seats so as not to frighten the cattle. Cowboys then drive the herd as close as possible, which is seldom closer than 50 yards from the line of windshields. Any nearer and the steers take fright and stampede, hightailing it off across the creek and over the hills on the horizon. But each cattleman has had a chance to judge them.

“He can study a 1,400 pound steer a city block away and tell you his weight within three pounds.

“Then the owner of the herd is called to the microphone attached to the big loudspeakers on top of the county agent’s car, and he tells the other cowmen just what brand and breed his string is, how much they cost, how many pounds of feed per day they have eaten, what each kind cost, how much they have gained, when he expects to sell them, and what his profit is, as of the present market. The cattlemen listen attentively to these figures, each comparing it with the cost of his own string.

“At noon the caravan halts for chuck at the Eddie Jones ranch. The food, as you might guess, is beef, the barbecue hind quarters of a prime Lyon county steer specially ordered from the Kansas City stockyards for this discriminating audience. To make sure they got a good one the Verdigris Valley ladies who prepared it got Big Walter Jones to put in the order himself.

“Big Walter is the most important cattleman of the region. His pastures in Kansas and Texas, if put together, would make up a sizeable part of the State of Rhode Island. He ships thousands of cattle a year, judges the market shrewdly, and even the big packing companies jump when Big Walter speaks out. So Big Walter went to the phone, called the Morrell Packing Company in Kansas City and told them to send him down a hind quarter off one of that string of steers which Floyd Lowder had shipped to market last week. Big Walter, visiting Floyd, had seen that string munching out in Floyd’s feeding corrals, and for 1,000 miles around there is no better judge of beef, either on the hoof or in the roaster, than Big Walter. You would agree if you could have seen the big chunks of it—each double the size of your head and beautifully roasted, set out on plank tables under the trees down by the creek on Eddie Jones’ ranch, and watched the juicy tender slices curl away from the sharp edges of the butcher knives as the hot meat was doused with hot sauce and put into barbecue sandwiches.

“How much did it cost? Well, nobody knows exactly. But the Verdigris Valley ladies had prudently allowed a pound of beef apiece for everyone present. Then there was the bread and coffee and sugar and thick country cream—something less than $30 in all, and everyone in the county welcome to come and stuff himself with barbecue. So, to pay for it, after everyone had finished and was gossipin in the shade, a couple of the boys passed the hat. You dropped in what you liked, according to how much money you made this year or what you figured you had eaten—anything from a nickel to a silver dollar. It has been a good year for most cowmen, and when the big Stetson hat had gone halfway through that crowd it was so heavy the boys figured it must have at least $30 so they knocked off and didn’t bother the rest of the folks.

“That’s the way they do business out here in the cow country, where the descendants of Anxiety IV—$15,000,000 worth of them this year—are far away red dots in the big blue stem and buffalo-grass pastures of Kansas. Cowmen think it’s a satisfactory way to do business when dealing with honest folks that you know—it’s much quicker than double entry bookkeeping and you don’t get your fingers all messed up with ink.

“The eastern visitor on vacation, driving west across the low mountains, heading down into the Mississippi valley and then beginning the slow climb toward the Rocky Mountains, is frequently mystified by the Barbecue Belt. He leaves the hot dog behind him as he crosses the Alleghenies. He enters the hamburger country at the Ohio valley. But as he nears the cattle country of the Southwest the barbecue stands displace the hamburger joints, and continue unbroken to the Pacific coast.

“If he samples Barbecue on the highway, he has eaten it at its worst. True Barbecue is seldom to be had, and is worth driving many miles to eat. In the strict definition of the term, Barbecue is any four footed animal—be it mouse or mastodon—whose dressed carcass is roasted whole. Occasionally it is a hog, often it is a fat sheep, but usually and at its best it is a fat steer, and it must be eaten within an hour of when it was cooked. For if ever the sun rises upon Barbecue its flavor vanishes like Cinderella’s silks and it becomes cold baked beef—staler in the chill dawn than illicit love.

“This is why it can never be commercialized, for no roadside stand could cook and sell a whole steer in a day. This is why true Barbecue, like true love, cannot be bought but must always be given, and so is found only as a part of lavish hospitality in the cow country.

“Consider, for instance, how the Floyd Ranch at Sedan, Kansas, recently entertained several hundred visiting cowmen on the beef tour of Chautauqua county.

“The cowboys first cut out from the Floyds’ herds a pair of the fattest 2-year-old steers. These were slaughtered, and the quartered carcasses hung in the cooler for proper aging. The day before the celebration a huge pit was dug, and in the early morning of the feast seasoned hickory logs were piled high in it and set ablaze. By mid afternoon it had burned down to a thick bed of red-hot coals. The two carcasses now come out of the cooler, the quarters are cut into 30 pound chunks and buried deep in the coals, which first sear the outside of the meat, sealing in the flavor, and then cook it slowly and succulently, the smell of baking beef and hickory smoke coming up through the coals and perfuming the country to attract discriminating eaters for miles around.

Other books

12 The Family Way by Rhys Bowen

Darkfall by Dean Koontz

Straight Cut by Bell, Madison Smartt

Revenge at Bella Terra by Christina Dodd

Mr. Mercedes by Stephen King

Points West (A Butterscotch Jones Mystery Book 5) by Jackson, Melanie

KILL ME IF YOU CAN (Dave Cunane Book 8) by Frank Lean

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne

The Betrayal by Ruth Langan

Wait Till I Tell You by Candia McWilliam