The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka (63 page)

Read The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka Online

Authors: Clare Wright

Tags: #HIS004000, #HIS054000, #HIS031000

Now there was the clean-up.

All the unclaimed dead and wounded were brought to the Camp in carts that afternoonâthree dray-loads full of maimed and lifeless bodies. Huyghue saw the mangled remains in the Camp hospital. The dead rebels' faces were

ghastly and passionately distorted

. Half-clothed, surprised from sleep, they remained frozen in a burlesque of battle. The nameless dead were unceremoniously buried at the cemetery on Monday. Regimental and civilian surgeons attempted to patch up the shattered limbs and ragged gashes of the wounded.

Four soldiers were dead: Privates William Webb (nineteen years) and Felix Boyle (thirty-two years) of the 12th Regiment and Michael Roney (twenty-two years) and Joseph Wall of the 40th (twenty years). At least nine more soldiers and police were wounded.

Captain Henry Wise, a twenty-five-year-old commissioned officer and the most popular soldier in the division, died of a gunshot wound to his leg on 21 December. He had only been in the country four weeks before he sustained his mortal injury leading the first line of troops into the Stockade. Before he died, Wise gamely announced that

his dancing was spoiled

. Henry Wise left a wife, Jane, to dance alone. Did she have a friend to comfort her at the Victoria Barracks in Melbourne, so forlorn, so far from home? Perhaps not; a Mrs Wise sailed for London in February 1855.

It is impossible to say exactly how many civilians died at the Stockade, in the surrounding tents or in the bush and the mine shafts where the dazed and wounded fled. There were many body counts that circulated in the following days and weeks. Peter Lalor famously published a list of the Eureka martyrs, in which he named twenty-two. Timothy Shanahan also counted twenty-two. Samuel Huyghue estimated thirty to forty. Dan Calwell reported to his American relatives a figure of thirty killed. In his diary entry for 6 December, Thomas Pierson noted twenty-five deaths. But some time later he scrawled in the margin,

time has proved that near 60 have died of the diggers in all

. Captain Thomas wrote in his official report that the casualties of the military action had been

great

but there was

no means of ascertaining correctly.

He estimated at least thirty killed on the spot, and

many more died of their wounds subsequently

. The numbers of injuries and fatalities, reported the

GEELONG ADVERTISER

on 8 December, were

more numerous than originally supposed

.

Among the known dead were Martin Diamond, Anne's husband; John Hynes, cousin to Bridget Hynes' husband; Patrick Gittens, who had been the best man at Bridget's wedding; Prussian Jew Teddy Thonen, the âlemonade seller'; Llewellyn Rowlands, who was shot in the chest by troopers outside his tent, half a mile from the Stockade. He wasn't Elizabeth Rowlands' husband, but maybe the troopers thought he was and deliberately sought him out for his wife's presumed treachery the previous morning. So many people caught in the wrong place at the wrong time, collateral damage of bitterly unfriendly fire. G. H. Mann simply recorded that

an onerous number of funerals were frequently passing to the cemetery for many days

.

Of these funeral corteges, Charles Evans described only oneâthe one that began our story. This is the coffin trimmed with white and followed by

a respectable and sorrowful group

. This is the coffin containing a dead woman, whose body was claimed but not named. This is the woman mercilessly butchered by a mounted trooper while she was pleading for the life of her husband. We don't know whether he was sparedâwhether she took the bullet or the bayonet for him. We don't know whether she left motherless children behind. We don't know how many other women may have been among the numbers of dead that could not be ascertained correctly. This is the woman who was slipped quietly into the earth by her weeping friends and loved ones, then slipped just as silently out of history.

The seismic front had passed, but there was one fatal aftershock. Directly after the riots, as the government would now refer to the storming of the Stockade, Ballarat was placed under martial law by order of Governor Hotham. There could be no light in any tent after 8pm. Reprisals were expected; the Camp was still jumpy as a cut snake. On Monday night, one trigger-happy sentry thought he heard gunfire coming from a tent close to the Camp. He opened fire.

Among the victims of last night's unpardonable recklessness

, wrote Charles Evans in his diary on Tuesday,

were a woman and her infant. The same ball which murdered the mother (for that's the term for it) passed through the child as it lay sleeping in her arms

. He also recorded that another young woman had a miraculous escape.

Hearing the reports of musketry and the dread whiz of bullets around her, she ran out of her tent to seek shelter. She had just got outside when a ball whistled immediately before her eyes passing through both sides of her bonnet.

This is the Woman of '54, the one who would write to the papers in 1884 to tell of the night she almost lost her life, a tale she related as an antidote to the noticeably chauvinistic thirtieth anniversary commemorations. This is the woman who called Humffray a coward. Closer to the action, Charles Evans had no trouble attesting to

monstrous acts like these polluting the soil with the innocent blood of men women and children

.

One woman's terror was another's opportunity. In the midst of the chaos of renewed firing, screaming and panic on that Monday night, a lone figure stole out from the Camp. Clouds obscured the moon, waning now, and the person chose the moment to run down the hill, keeping close to the picket fence to avoid holes and tent ropes.

In an instant

, recalled Samuel Huyghue,

a dozen rifles were pointed at the moving object when a ray of moonlight befriended her (for it proved to be a woman) and she got off scatheless

. The soldiers were more discerning now than they had been the previous morning.

As soon as her garments revealed her sex the deadly weapons were lowered,

wrote Huyghue.

It was a close shave but perhaps she never realised to the full the danger she escaped.

It's more likely this woman was fully aware of the risks of stealing into the Camp to see her husband, who was one of the prisoners. But Anastasia Hayes was nothing if not a risk-taker. She had five children and a newborn baby, but still she found the nerve to broker a

secret communication

with Timothy through the connivance of the lockup keeper, who was subsequently arrested for his perfidy. Huyghue's own suspicion was that Anastasia was working as a spy for the reform league and that part of her plan was to rescue the prisoners by creating a diversion.

Paranoia had gripped the Camp by now. For good measure, the prisoners were transferred from the âlogs' to the zinc-lined commissariat store. This means the women who had stayed at the Camp during the previous terrifying days, including Ellen Neill and baby Fanny, must have been moved out. Maggie Johnston recorded the week's bizarre arrangements in her diary.

December 3 Sunday

The awful day of the attack made at the Eureka at 5 in the morning.

December 4 Monday

All day long funerals passing.

December 5 Tuesday

Somewhat similar.

December 6 Wednesday

Mrs Lane staying with me for a week.

By the end of that train wreck of a month, the bulk of the funerals were over, the shops were once again open, mining operations were in full steam and the rattle of the windlass chimed in syncopated rhythm with squeezeboxes, street bands, shrieking children and barking dogs.

Peter Lalor, with the connivance of Stephen and Jane Cuming, was in hiding in Geelong, under the care of Alicia Dunne. Along with Lalor, Frederick Vern, George Black and James McGill had a £500 price tag on their heads. Thirteen menâincluding Timothy Hayes, Raffaello Carboni and the

nigger rebel

, African-American John Josephâwere on their way to Melbourne to be tried for treason. Henry Seekamp had been arrested in his home, with Clara and her children looking on, and would contest a charge of sedition.

The rest of the prisoners were released to the ruins of their burnt-out tents, grief-stricken kin and uncertain futures. Robert Rede's report for the last week of December noted a population increase of 855 women and 1955 children, and a decrease of 4130 men.

A better state of order is returning

, he wrote,

and the miners are resuming workâ¦little gold has been raised

.

36

Eureka Wright, whose parents Thomas and Mary Wright were in their tent inside the stockade when it was stormed, celebrated her first birthday.

Dear Jamie and I spent a quiet day all alone

, wrote Maggie Johnston.

Our first Christmas after our marriage.

Her baby quickened.

A year earlier, Thomas Pierson had wondered what fate would befall him, Frances and Mason by the next Christmas. Now, he joined with thousands of other drunk and sunburnt people thronging the long Main Road that ran through the Flat to rejoice at the birth of Christ and other small miracles. It was a hundred degrees; the flies were as thick as Connecticut snow, and Thomas reckoned he would never grow accustomed to this strange country. Yuletide tells a story of birth, hope and promise in a spiritual sanctum, but for Thomas and Frances, after all they had seen,

the exiles dream of home is past

.

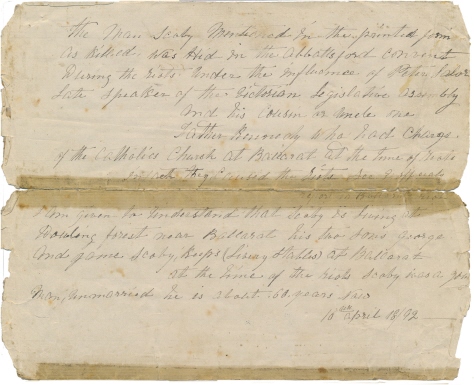

Note written by Catherine Bentley on the back of a copy of the petition to free her husband. Dated 10 April 1892, the anniversary of James Bentley's suicide. Transcription p. 479.

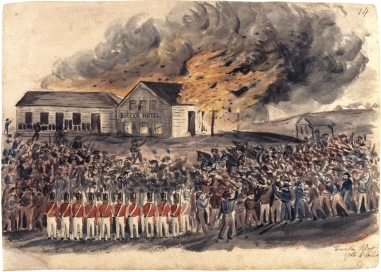

The Bentleys' dreams go up in smoke, as witnessed by Charles Doudiet, 1854.