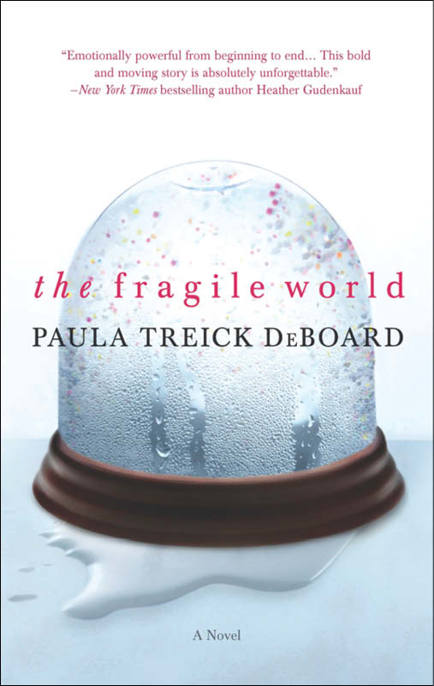

The Fragile World

Authors: Paula Treick DeBoard

From the author of stunning debut

The Mourning Hours

comes a powerful new novel that explores every parent’s worst nightmare…

The Kaufmans have always considered themselves a normal, happy family. Curtis is a physics teacher at a local high school. His wife, Kathleen, restores furniture for upscale boutiques. Daniel is away at college on a prestigious music scholarship, and twelve-year-old Olivia is a happy-go-lucky kid whose biggest concern is passing her next math test.

And then comes the middle-of-the-night phone call that changes everything. Daniel has been killed in what the police are calling a “freak” road accident, and the remaining Kaufmans are left to flounder in their grief.

The anguish of Daniel’s death is isolating, and it’s not long before this once-perfect family finds itself falling apart. As time passes and the wound refuses to heal, Curtis becomes obsessed with the idea of revenge, a growing mania that leads him to pack up his life and his anxious teenage daughter and set out on a collision course to right a wrong.

An emotionally charged novel,

The Fragile World

is a journey through America’s heartland and a family’s brightest and darkest moments, exploring the devastating pain of losing a child and the beauty of finding the way back to hope.

Praise for the novels of Paula Treick DeBoard

“Emotionally powerful from beginning to end, Paula Treick DeBoard’s novel

The Fragile World

chronicles the heartbreaking dissolution of a family after tragic loss. Exquisitely told, this bold and moving story is a study in grief and the transforming power of love. Absolutely unforgettable.”

—Heather Gudenkauf,

New York Times

bestselling author of

The Weight of Silence

“A heart-stopping series of events drives

The Fragile World,

as Paula Treick DeBoard skillfully alternates between a father and daughter dealing with tragic loss. The result is a gripping read, but one that delivers, by the book’s end, a beautiful reminder of the resilience of love.”

—Karen Brown, author of

The Longings of Wayward Girls

“A coming-of-age tale about a family in crisis expertly told by Ms. DeBoard.

The Fragile World

examines how profound loss changes all who are forced to come to terms with it. Touching and compelling, it will move you.”

—Lesley Kagen,

New York Times

bestselling author of

Whistling in the Dark

and

The Resurrection of Tess Blessing

.

“Assured storytelling propels DeBoard’s first novel.… What most compels is the observant Kirsten’s account of how a small town and a family disintegrate under the weight of the tragedy.”

—

Publishers Weekly

on

The Mourning Hours

“Rich and evocative…compelling.”

—

RT Book Reviews

on

The Mourning Hours

Also by Paula Treick DeBoard

THE MOURNING HOURS

THE FRAGILE

WORLD

Paula Treick DeBoard

For my parents, who taught me that a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single packed-to-the-gills station wagon.

Contents

The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.

—Franklin D. Roosevelt

Also, blenders.

—Olivia Kaufman

prologue

Olivia

I

n the beginning there was Daniel. He was the only child my parents ever needed, because he was perfect. His first word was

magnet

and, the story goes, he said it while looking at the refrigerator, where my mother had spelled out D-A-N-I-E-L in brightly colored letters. Other kids might have memorized the stories their parents read to them from the Little Golden Books, but my mother always swore that Daniel was actually reading, even though he wasn’t three years old yet. By the time he was five and still belted into a child seat in the back of Mom’s car, he was already reading every sign on the road: City Limit and Closing Sale and Fresh Donuts. His early teachers strongly suggested that he skip grades, and if my parents hadn’t worried about his size—smallish—and his sociability—shyish—he would probably have been one of those kids who make the news when they graduate from university at age twelve.

When he was six years old, Mom enrolled Daniel in piano lessons, since he had taken to singing road signs as they drove and later banging out the tunes on the kitchen table with his fork and spoon. Prompted by the sight of the golden arches, he would launch into “Two all-beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese...” and he could produce, on demand, the exact jingle that matched every car dealership in the greater Sacramento area. When I was born—and just for a moment, let’s pause to consider why, exactly, my parents would want another child when surely they had everything a parent could want in Daniel—he was already on his way to becoming a musical prodigy.

Physically, our lives revolved around Daniel and his music. Our funky, turn-of-the-last-century house near downtown Sacramento was crammed full with musical instruments—the upright piano in the living room, the drum set at the top of the stairs, his guitar propped against one wall or another. I was convinced that he was the only person on earth who could make a recorder look cool.

When Daniel was in the seventh grade, Mom picked me up from kindergarten one afternoon and drove me across town to his middle school auditorium for the annual talent show. The other kids were truly kids—they performed bright, cheery dance routines in spangly costumes, they lip-synced to pop songs, they executed strange karate routines that involved a lot of posturing and choppy air kicks. Daniel was the last one to take the stage, no doubt because the organizers knew he was the best. He announced that he was playing “Flight of the Bumblebee” by Rimsky-Korsakov and the entire gym went quiet with the opening notes. His fingers flew confidently over the keys; if he was intimidated in any way by hundreds of eyes on him, it didn’t show. Mom had tried to convince him earlier that day to bring the sheet music as a backup, but Daniel had only tapped his head with one finger, meaning

It’s all up here.

It was the first time I realized that Daniel was really great, something special.

What a disappointment I must have been, must still be. I took three years of piano lessons and barely advanced beyond the “early learner books.” I remember one song, played with my right thumb on middle C and my right index finger on D.

See the bear, on two feet, begging for a bite to eat.

All I had to do was toggle my fingers between the two keys, and yet somehow I couldn’t help but hit adjacent keys or lose the simple beat, giving up in a frustrated squash of all my fingers against the keys at once. Inside, a voice was saying, regular as a metronome:

Don’t mess up. Get it right. Play the notes.

It didn’t seem hard—but somehow I couldn’t do it.

On the day of what would be my last lesson, Mom arrived at my teacher’s house as I was fumbling my way through a simple scale I’d spent hours practicing. I’d been biting my lip in deep concentration, but when I saw her listening in the doorway, I burst into tears.

“It’s okay,” she said as we drove home, my tears finally drying against my cheeks. “You know, I’m not a musical person, and your father isn’t, either. We’re all talented in different ways. I don’t want you to feel bad about this, all right?”

But I did feel bad. Not because I had any illusions about my musical ability—even as a third grader, I understood that the awkward clunking sounds I made at the piano were never going to evolve into the effortless music Daniel made. It hurt me, though, to think that my mother had given up on me so early, that she had accepted my lack of talent so easily. I might have resented the hell out of her for it later on, but at that moment, I wanted her to fight for me—or at least give the slightest acknowledgment that I was worth fighting for, even if it was a lie. Something like: “Olivia, you have hidden potential....”

But no. I was an eight-year-old failure.

As he got older, Daniel seemed to float through our lives on his way from one practice or event to another—concert band, musical ensemble, pep band, a steel drum band that met before school, a band that jammed for hours in our garage after school. He was a member of the youth symphony orchestra; he played piano for the spring musical his junior and senior years. Colleges fell over themselves with scholarship offers—on top of everything else, Daniel had maintained a 4.3 grade point average throughout high school. Basically, he was that one-in-a-million kid, the one who participated in everything and volunteered for everything and did a fan-

freaking-

tastic job at everything. His face—pale beneath a shock of dark hair—appeared dozens of times in his high school yearbooks, the margins crammed with notes from friends and phone numbers from hopeful admirers.

Sometimes I thought his success would have been easier to take if Daniel had been an asshole, some mean-spirited genius who could only look down his nose at everyone else. But the thing was—he was so damn nice. He was the best big brother you could have. He never once told me to go away because I was bothering him. He never once told me that I sucked at the piano or worse, showered me with pity. He made up silly songs for me every year as a birthday present, and when he got his license, he once spent an entire Saturday afternoon driving me around Sacramento in search of the best sno-cone. When he went away to Oberlin, he sent emails that were just for me, separate from the ones he sent to Dad and Mom, filled with jokes and links to funny things he’d found online, like penguins bowling and dogs chasing their tails. He liked to set cat videos to his own music, little things he composed for a joke and that I thought were genius.

Basically, I worshipped him. And as bad as I felt for disappointing Dad and Mom, I never once felt that I had disappointed Daniel. You just couldn’t feel bad about yourself around him, because he didn’t have that effect on people.

In the beginning, there was Daniel.

Until one day, there wasn’t.

The obituary in

The Sacramento Bee,

written by Aunt Judy when neither of my parents was up to the task, left out everything interesting and reduced my brother to the barest of facts: Daniel Owen Kaufman was predeceased by both his paternal and maternal grandparents. He is survived by his immediate family, parents Curtis and Kathleen Kaufman and sister Olivia. He is also survived by an uncle and aunt, Jeff and Judy Eberle, cousin, Chelsey, and friends throughout the Sacramento and Oberlin, Ohio, areas.

Survived,

when you think about it, is a funny term.

Survived

implies that we were there on the sinking ship, that somehow we got on the lifeboat, but Daniel didn’t.

Survived

suggests that we were pulled from the wreckage of the collapsed building, but Daniel wasn’t.

Survived

also means we kept on living—and I’m not sure that’s true.

Oh, we were still alive in the biological sense of hearts beating and lungs inflating. Dad kept on showing up at Rio Americano High, where he had taught physics for so long that he was almost an institution unto himself. Mom, who had been a buyer for an antiques dealer before branching into her own furniture restoration business, threw herself into her work with a passion that bordered on mania. And me—I guess you could say that I kept going, too. I was still living and breathing and getting decent scores on my homework. I still basically

looked

like a normal kid. But nothing ever

felt

right.

Somehow, as the years passed, Daniel was still there. Not in some weird, spiritual way, as if his ghost were haunting our upstairs hallway or his profile had appeared on a moldy tortilla, but in the hold that he had over me—every memory of my childhood had Daniel in it, hovering at the edges like an orb sneaking into the background of a photo. Moving forward—

moving past the incident,

as our family therapist had said in her nice-nice way, as if everything bad could be covered over with a euphemism—was like stepping into a vacuum, a World Without Daniel, a blank space, an empty room. Some people, I heard, kept phone messages from their dead loved ones, replaying them for a dose of comfort, a reassurance of immortality. Mom’s way of keeping Daniel alive was to say his name as much as possible, to bring him into conversations like that old saying I’d learned about Jesus,

the silent guest at every meal.

Seeing a notice in the paper about a soloist in a holiday concert, she’d say “That name sounds familiar. I wonder if that’s the younger sister of what’s-her-name, the one who used to play clarinet with Daniel?” Cleaning out our junk drawer: “This must be the missing piece to Daniel’s little gadget, that little thingamajig that he used to spin around on the patio....” For no reason at all: “Remember when we rode the cable cars to the wharf and Daniel...”

Yes, Mom. I remember. We know.

Dad and I, by tacit consent, mentioned his name less and less, until we stopped saying it at all. The space Daniel had occupied was now a silent void, a sort of musical black hole that we tried to fill with the television, with random chitchat about things that didn’t matter at all. It was as if Daniel had taken with him all the arias and sonatas and symphonies, all the pianissimos and fortes, all the beauty and improvisation.

Dad and I kept our silence because it was too hard—it was shitty, frankly—to acknowledge that Daniel had ever existed, because then we had to remind ourselves that he didn’t exist anymore, that he was, and would always be, dead.