The Friar of Carcassonne (33 page)

Pedro Berruguete's late-fifteenth-century rendering of St. Dominic presiding over an auto-da-fé (the victims are lower right). Hanging in Madrid's Prado, it is a celebrated example of the anachronistic “inquisitorializing” of Dominic's biography. The inquisition did not exist in the saint's lifetime.

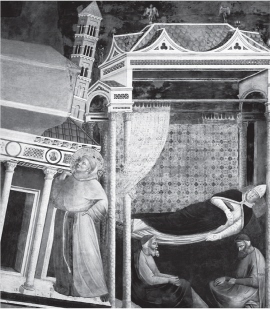

Giotto's depiction of Pope Innocent III dreaming of Francis of Assisi supporting the weight of St. John Lateran, then the principal church of Christendom and, as such, a symbol of the Church itself.

M

ANY PEOPLE HAVE CONTRIBUTED

to the making of this book, through their help, consideration, and kindness. In the southwest of France, home to the story of Brother Bernard, the invaluable assistance of the indefatigable journalist Pascal Alquier, aka Monsieur Toulouse, opened doors for me, led me to scholars and scholarship, and provided welcome shelter for me in his flat near the Basilica of St. Sernin. In the countryside Jean-Pierre Pétermann and his wife, Joelle, welcomed me into their home in Auterive several times, and when Jean-Pierre (a medical professional in real life but in truth a modern-day Cathar) and I returned from our photographic safaris of Languedoc, a hearty meal always awaited, as did a fine bottle from the local bounty. In the mornings after the nights before, Jean-Pierre and Joelle's young, voluble triplets, Aymeri, Aurenca, and Aélis, made sure that we did not shirk our duty to hit the road again brightish and earlyish.

Other denizens of Languedoc edified, informed, and welcomed, including scholar Father Georges Passerat, troubadour Christian Salès, cultural impresario Robert Cavalié, radio journalist Laura Haydon, and writer Suzanne Lowry. In Carcassonne, my thanks also to Jean-Louis Gasc, who conducted me on a tour of the ramparts that was exclusively devoted to the trial of Bernard Délicieux. In the Bourg, at the Centre d'Ãtudes Cathares, the staff assembled hard-to-get monographs and articles on the history of

la rage carcassonnaise

. They simplified my research immensely andââFrancophobes take note and repentâwent out of their way to do their job, even to the point of making up for a missed rendezvous (because of a hospitalized child!) by going to the center and photocopying documents for me during its August closing, no less.

In the Roussillon, on the tracks of Bernard's failed plot, I was welcomed in Camélas once again by Vladimir and Yovanka Djurovic and Martine and Francis Péron. Farther north, in King Philip the Fair's scheming metropolis, my research sojourns in Paris were made even more enjoyable by the hospitality of Heidi Ellison and Sandy and Elisabeth Whitelaw. In London, home to so many good bookstores, my stays there were always enlivened by the warm welcome of Kate Griffin and her daughters Flo and Georgie. In Toronto, I would like to thank Helen Mercer and Eleanor Wachtel for their hospitality and support. In Ottawa, a similar thank-you to artist Patrick Cocklin and, of course, to my dad, Daniel O'Shea.

Most of this book was written and researched in Providence, Rhode Island. As in the past, the eagle eye and writerly advice of novelist pal Eli Gottlieb, out in Boulder, Colorado, have been much appreciated. I'd like also to thank two hyperliterate lawyers, Fred Stolle of Providence and Edward Hernstadt of New York City, for training their gaze on the manuscriptâparticularly the third chapterâfor signs betraying the legal neophyte. Ed and his wife, Maia Wechsler, old friends from our Paris days together, have made their Dumbo loft in Brooklyn a second home for me in my frequent stays in the city.

Here in my first home, as ever, a heartfelt thank-you to my family, Jill, Rachel, and Eve, for their supportâeven though daughters Rachel and Eve insist on taking obscure revenge for my monomania by always referring to my heretics as “Cathires.” To those friends here who did not take the subject of my research as an instance of rôtisserie-league Catholicism, I say thank you: Claude Goldstein, Allen Kurzweil, Rosemary Mahoney, Bill Viall. To those who did, I say nothing. A debt of gratitude is also owed to two medievalists resident in Rhode Island, both specialists of the fourteenth century (providential, no?), who led me from the path of error: Joëlle Rollo-Koster and Alizah Holstein.

Professionally, I owe much to agent Chuck Verrill, who guided this project expertly from the outset. I am also indebted to talented designer Cara T. Collins for escorting me onto the Web in style (

stephenosheaonline.com

âplease feel free to check it out and leave comments, suggestions, brickbats, etc., for me on this present work at the contact point provided; I am much better at responding to e-mail than to snail mail). And thanks again to publishers Scott McIntyre (Canada), George Gibson (United States), and Peter Carson (United Kingdom) for their untiring support and confidence. I, alas, am wholly responsible for whatever infelicities and inaccuracies the book contains.

Last, but most important, a word about research. Whatever else one may say about America, here in New England the sheer profusion of great libraries, digital archives, easy access to interlibrary loans and the like is nothing less than world-class, a true example of democracy in action. Many thanks to my research assistant, Jennifer Schneider, for attacking the stacks when I couldn't. A recent graduate of Brown, Jenny was able to find just about anything at the libraries of her alma mater.

Elsewhere, the staff at the Fox Point branch of the Providence public library system pulled some rabbits out of their hats, as did the friendly librarians of the Providence Athenæum. And for those mendicant obscurities unavailable anywhere else, I am indebted to Providence College and its research library, its stacks admirably open to the general public. I enjoyed slipping in there, with Brother Bernard hidden in my backpack, for Providence College is the only university in North America run by the Dominicans. It has a good men's basketball team, the Friars.

A narrative with a claim to immediacy on events long past necessitates a good deal of notes. As many, but not all, of the details about Brother Bernard's activities come from his trial, I will point the skeptical reader frequently to Jean Duvernoy's French translation of the trial transcript. Decisions and inferences made by me and others will also be discussed. Mundane matters of fact found in all his previous biographies will not be cited, as that would put everyone to sleep. Where the biographers differ, however, will be flagged.

Also cited are sources not directly germane to Bernard, such as, for example, those dealing with the affair of the Templars. And I will also provide additional material in the notes that I could not somehow shoehorn into the main narrative. These digressions, I hope, may lead in a roundabout way to a better understanding of Délicieux and his place in history. Some are amusing, some appalling.

Bibliographical detail in the notes is provided the first time a work is cited. After that, abbreviated entries are the rule. If you don't want to lose your temper flipping back through the notes to see where such-and-such a book is first mentioned, save yourself the trouble and go to the bibliography. Last, the publishing date covers the edition I used.

B

ROTHER

B

ERNARD

*

Those who commissioned him sought to bolster local pride and regional

identity, and to instruct and edify:

Tastes changed and the history painting went out of fashion. The most memorable epitaph for the genre came from the savagely witty pen of Saki (Hector Hugh Munro) in his story “The Reticence of Lady Anne”: “They leaned towards the honest and explicit in art, a picture, for instance, that told its own story, with generous assistance from its title. A riderless warhorse with harness in obvious disarray, staggering into a courtyard full of pale swooning women, and marginally noted âBad News,' suggested to their minds a distinct interpretation of some military catastrophe. They could see what it was meant to convey, and explain it to friends of duller intelligence.”

The Complete Saki

, London, 1998, pp. 46â48. For immediate gratification, the story can be found online:

http://haytom.us/showarticle.php?id=119

.

*

his three major biographers:

Jean-Barthélemy Hauréau,

Bernard Délicieux

et l' inquisition albigeoise (1300â1320),

Paris, 1877; Michel de Dmitrewski, “Fr. Bernard Délicieux, O.F.M. Sa lutte contre L'Inquisition de Carcassonne et d'Albi, son procès, 1297â1319,”

Archivum Franciscanum

Historicam

, 17, 1924, pp. 183â218, 313â337, 457â488; 18, 1925, pp. 3â32; Alan Friedlander,

The Hammer of the Inquisitors: Brother Bernard Délicieux

and the Struggle Against the Inquisition in Fourteenth-Century

France

, Leiden, 2000. To these larger works must be added two invaluable monographs: Jean-Louis Biget, “Autour de Bernard Délicieux. Franciscanisme et société en Languedoc entre 1295 et 1330,”

Revue

d' histoire de l'Eglise de France

, 70, 1984, pp. 75â93; Yves Dossat, “Les origines de la querelle entre Prêcheurs et Mineurs provençaux,”

Cahiers

de Fanjeaux

, 10, 1975, pp. 315â354. These scholars produced other works germane to Bernard's story, but the five works cited here form the core material, aside from the transcripts of the trial. Their other works, and those of other scholars to treat the story, appear in the bibliography.

*

an American historian undertook the task of collating, transcribing and

publishing:

Alan Friedlander,

Proâcessus Bernardi Delitiosi: The Trial of Fr.

Bernard Délicieux, 3 Septemberâ8 September 1319,

Philadelphia, 1996.

*

rendered the Latin of the original into a modern vernacular:

Jean Duvernoy,

Le Procès de Bernard Délicieux 1319

, Toulouse, 2001.

*

the memory of Brother Bernard Délicieux:

The Franciscan is not universally revered. While inspecting the lower town of Carcassonne (called the Bourg in the main narrative) in the summer of 2009, I entered an old cathedral, St. Michel, which stands more or less unchanged since Bernard's time. I was alone. I took notes, which I didn't end up using, on the interior of this fine example of Languedocian Gothic. A figure approached from a side aisle, smiling, thirtysomething, in priestly attire. I asked him about his church, its past and present. He was very affable, knowledgeable, a learned clergyman affiliated with the Dominicans. His edifying explanations drawing to a close, he asked me why I was so interested in the church. I told him I was researching a book on Bernard Délicieux. It was if I had slapped his face with a large, wet fish. He recovered his smile, then snapped in premature parting, “On dit tout et n'importe quoi à son sujet!”âdon't believe what you hear about him.

1. T

HE

B

RIDGE AT

R

OME

*

the drudges of his

Wasteland

:

The passage is found in T.S. Eliot,

The

Wasteland

:

i The Burial of the Dead

, 60â64. From T. S. Eliot,

Collected

Poems, 1909â1962

, New York, 1963.

*

the Ponte St. Angelo:

The beautiful bridge still stands and is reserved exclusively for pedestrians, a measure enacted by Mussolini in the early 1930s.

*

Dante commanded his underworld denizens:

Dante,

Inferno

, xviii 27â32:

come i Roman per l'essercito molto,

l'anno del giubileo, su per lo ponte

hanno a passar la gente modo colto,

che da l'un lato tutti hanno la fronte

verso ' l castello e vanno a Santo Pietro,

de l'altra sponda vanno verso ' l monte.

de l'altra sponda vanno verso ' l monte.

I used in the narrative the verse translation of Pinsky,

Inferno

. It is clear. A more stately, but not altogether transparent, translation of the passage was made by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, published to great fanfare in 1867:

Even as the Romans, for the mighty host,

The year of Jubilee, upon the bridge,

Have chosen a mode to pass the people over;

For all upon one side towards the Castle

Their faces have, and go unto St. Peter's;

On the other side they go towards the Mountain

The Castle is undoubtedly Hadrian's mausoleuem, aka the Castel St. Angelo. The Mountain or mount is the Gianicolo (Janiculum), the tall, distant ridge beyond the Borgo of central Rome and another bend of the Tiber. It is not one of the Seven Hills.

*

“Day and night two priests stood at the altar of St. Paul's”:

The chronicler is William Ventura, cited in Paul Hetherington,

Medieval

Rome: A Portrait of the the City and Its Life

, New York, 1994, p. 79.

*

he was moved to undertake his

Nuova Cronica

:

Rome impressed him so much that he thought of Florence: “It was the most marvellous thing that was ever seen . . . Finding myself on that blessed pilgrimage in the holy city of Rome, beholding the great and ancient things therein, and reading the stories and the great doings of the Romans, written by Virgil and Sallust and Lucas and Titus Livius and Valerius and Paulus Orosius, and other masters of history . . . I resolved myself to preserve memorials . . . for those who should come after . . . But considering that our city of Florence, the daughter and creature of Rome, was rising, and had great things before her, whilst Rome was declining, it seemed to me fitting to collect in this volume and new chronicle all the deeds and beginnings of the city of Florence . . . and to follow the doings of the Florentines in detail.” Giovanni Villani,

Nuova Cronica

, viii 36. From translator Rose E. Selfe,

Villani's Chronicle,

Being Selections from the First Nine Books of the Croniche Fiorentine

of Giovanni Villani

, London, 1906, p. 321. In this section Villani estimates a crowd of 200,000 pilgrims is present every day of that year in Rome.