The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement (14 page)

Read The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement Online

Authors: Eliyahu Goldratt

We keep going. The die spins on the table and passes from hand to hand. Matches come out of the box and move from bowl to bowl. Andy’s rolls are—what else?—very average, no steady run of high or low numbers. He is able to meet the quota and then some. At the other end of the table, it’s a different story.

"Hey, let’s keep those matches coming.’’

"Yeah, we need more down here.’’

"Keep rolling sixes, Andy.’’

"It isn’t Andy, it’s Chuck. Look at him, he’s got five.’’ After four turns, I have to add more numbers—negative numbers—to the bottom of the chart. Not for Andy or for Ben or for Chuck, but for Dave and Evan. For them, it looks like there is no bottom deep enough.

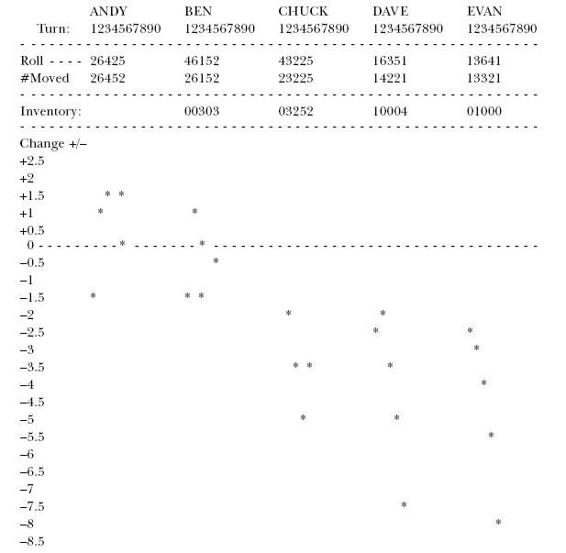

After five rounds, the chart looks like this:

"How am I doing, Mr. Rogo?’’ Evan asks me.

"Well, Evan... ever hear the story of the Titanic?’’ He looks depressed.

"You’ve got five rounds left,’’ I tell him. "Maybe you can pull through.’’

"Yeah, remember the law of averages,’’ says Chuck. "If I have to wash dishes because you guys didn’t give me enough matches . . .’’ says Evan, letting vague implications of threat hang in the air.

"I’m doing my job up here,’’ says Andy.

"Yeah, what’s wrong with you guys down there?’’ asks Ben.

"Hey, I just now got enough of them to pass,’’ says Dave. "I’ve hardly had any before.’’

Indeed, some of the inventory which had been stuck in the first three bowls had finally moved to Dave. But now it gets stuck in Dave’s bowl. The couple of higher rolls he had in the first five rounds are averaging out. Now he’s getting low rolls just when he has inventory to move.

"C’mon, Dave, gimme some matches,’’ says Evan.

Dave rolls a one.

"Aw, Dave! One match!’’

"Andy, you hear what we’re having for dinner tonight?’’ asks Ben.

"I think it’s spaghetti,’’ says Andy.

"Ah, man, that’ll be a mess to clean up.’’

"Yeah, glad I won’t have to do it,’’ says Andy.

"You just wait,’’ says Evan. "You just wait ’til Dave gets some good numbers for a change.’’

But it doesn’t get any better.

"How are we doing now, Mr. Rogo?’’ asks Evan.

"I think there’s a Brillo pad with your name on it.’’

"All right! No dishes tonight!’’ shouts Andy.

After ten rounds, this is how the chart looks . . .

I look at the chart. I still can hardly believe it. It was a balanced system. And yet throughput went down. Inventory went up. And operational expense? If there had been carrying costs on the matches, operational expense would have gone up too.

What if this had been a real plant—with real customers? How many units did we manage to ship? We expected to ship thirty-five. But what was our actual throughput? It was only twenty. About half of what we needed. And it was nowhere near the maximum potential of each station. If this had been an actual plant, half of our orders—or more—would have been late. We’d never be able to promise specific delivery dates. And if we did, our credibility with customers would drop through the floor.

# Dave’s inventory for turns 8,9, and 10 is in double digits, respectively rising to 11 matches, 14 matches, and 17 matches.

All of that sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

"Hey, we can’t stop now!’’ Evan is clamoring.

"Yea, let’s keep playing,’’ says Dave.

"Okay,’’ says Andy. "What do you want to bet this time? I’ll take you on.’’

"Let’s play for who cooks dinner,’’ says Ben.

"Great,’’ says Dave.

"You’re on,’’ says Evan.

They roll the die for another twenty rounds, but I run out of paper at the bottom of the page while tracking Dave and Evan. What was I expecting? My initial chart ranged from +6 to −6. I guess I was expecting some fairly regular highs and lows, a normal sine curve. But I didn’t get that. Instead, the chart looks like I’m tracing a cross-section of the Grand Canyon. Inventory moves through the system not in manageable flow, but in waves. The mound of matches in Dave’s bowl passes to Evan’s and onto the table finally—only to be replaced by another accumulating wave. And the system gets further and further behind schedule.

"Want to play again?’’ asks Andy.

"Yeah, only this time I get your seat,’’ says Evan. "No way!’’ says Andy.

Chuck is in the middle shaking his head, already resigned to defeat. Anyway, it’s time to head on up the trail again. "Some game that turned out to be,’’ says Evan. "Right, some game,’’ I mumble.

For a while, I watch the line ahead of me. As usual, the gaps are widening. I shake my head. If I can’t even deal with this in a simple hike, how am I going to deal with it in the plant?

What went wrong back there? Why didn’t the balanced model work? For about an hour or so, I keep thinking about what happened. Twice I have to stop the troop to let us catch up. Sometime after the second stop, I’ve fairly well sorted out what happened.

There was no reserve. When the kids downstream in the balanced model got behind, they had no extra capacity to make up for the loss. And as the negative deviations accumulated, they got deeper and deeper in the hole.

Then a long-lost memory from way back in some math class in school comes to mind. It has to do with something called a covariance, the impact of one variable upon others in the same group. A mathematical principle says that in a linear dependency of two or more variables, the fluctuations of the variables down the line will fluctuate around the maximum deviation established by any preceding variables. That explains what happened in the balanced model.

Fine, but what do I do about it?

On the trail, when I see how far behind we are, I can tell everyone to hurry up. Or I can tell Ron to slow down or stop. And we close ranks. Inside a plant, when the departments get behind and work-in-process inventory starts building up, people are shifted around, they’re put on overtime, managers start to crack the whip, product moves out the door, and inventories slowly go down again. Yeah, that’s it: we run to catch up. (We always run, never stop; the other option, having some workers idle, is taboo.) So why can’t we catch up at my plant? It feels like we’re always running. We’re running so hard we’re out of breath.

I look up the trail. Not only are the gaps still occurring, but they’re expanding faster than ever! Then I notice something weird. Nobody in the column is stuck on the heels of anybody else. Except me. I’m stuck behind Herbie.

Herbie? What’s he doing back here?

I lean to the side so I can see the line better. Ron is no longer leading the troop; he’s a third of the way back now. And Davey is ahead of him. I don’t know who’s leading. I can’t see that far. Well, son of a gun. The little bastards changed their marching order on me.

"Herbie, how come you’re all the way back here?’’ I ask.

"Oh, hi, Mr. Rogo,’’ says Herbie as he turns around. "I just thought I’d stay back here with you. This way I won’t hold anybody up.’’

He’s walking backwards as he says this.

"Hu-huh, well, that’s thoughtful of you. Watch out!’’

Herbie trips on a tree root and goes flying onto his backside. I help him up.

"Are you okay?’’ I ask.

"Yeah, but I guess I’d better walk forwards, huh?’’ he says. "Kind of hard to talk that way though.’’

"That’s okay, Herbie,’’ I tell him as we start walking again. "You just enjoy the hike. I’ve got lots to think about.’’

And that’s no lie. Because I think Herbie may have just put me onto something. My guess is that Herbie, unless he’s trying very hard, as he was before lunch, is the slowest one in the troop. I mean, he seems like a good kid and everything. He’s clearly very conscientious—but he’s slower than all the others. (Somebody’s got to be, right?) So when Herbie is walking at what I’ll loosely call his "optimal’’ pace—a pace that’s comfortable to him —he’s going to be moving slower than anybody who happens to be behind him. Like me.

At the moment, Herbie isn’t limiting the progress of anyone except me. In fact, all the boys have arranged themselves (deliberately or accidentally, I’m not sure which) in an order that allows every one of them to walk without restriction. As I look up the line, I can’t see anybody who is being held back by anybody else. The order in which they’ve put themselves has placed the fastest kid at the front of the line, and the slowest at the back of the line. In effect, each of them, like Herbie, has found an optimal pace for himself. If this were my plant, it would be as if there were a never-ending supply of work—no idle time.

But look at what’s happening: the length of the line is spreading farther and faster than ever before. The gaps between the boys are widening. The closer to the front of the line, the wider the gaps become and the faster they expand.

You can look at it this way, too: Herbie is advancing at his own speed, which happens to be slower than my potential speed. But because of dependency,

my

maximum speed is the rate at which Herbie is walking. My rate is throughput. Herbie’s rate governs mine. So Herbie really is determining the maximum throughput.

My head feels as though it’s going to take off.

Because, see, it really doesn’t matter how fast any

one

of us can go, or does go. Somebody up there, whoever is leading right now, is walking faster than average, say, three miles per hour. So what! Is his speed helping the troop

as a whole

to move faster, to gain more throughput? No way. Each of the other boys down the line is walking a little bit faster than the kid directly behind him. Are any of them helping to move the troop faster? Absolutely not. Herbie is walking at his own slower speed. He is the one who is governing throughput for the troop as a whole.

In fact, whoever is moving the slowest in the troop is the one who will govern throughput. And that person may not always be Herbie. Before lunch, Herbie was walking faster. It really wasn’t obvious who was the slowest in the troop. So the role of Herbie— the greatest limit on throughput—was actually floating through the troop; it depended upon who was moving the slowest at a particular time. But overall, Herbie has the least capacity for walking. His rate ultimately determines the troop’s rate. Which means—

"Hey, look at this, Mr. Rogo,’’ says Herbie.

He’s pointing at a marker made of concrete next to the trail. I take a look. Well, I’ll be...it’s a milestone! A genuine, honest-to-god milestone! How many speeches have I heard where somebody talks about these damn things? And this is the first one I’ve ever come across. This is what it says:

<---5-->

miles

Hmmm. It must mean there are five miles to walk in both directions. So this must be the mid-point of the hike. Five miles to go.

What time is it?

I check my watch. Gee, it’s 2:30 P.M. already. And we left at 8:30 A.M. So subtracting the hour we took for lunch, that means we’ve covered five miles ...in five hours?

We aren’t moving at two miles per hour. We are moving at the rate of one mile per hour. So with five hours to go . . .

It’s going to be DARK by the time we get there.

And Herbie is standing here next to me delaying the throughput of the entire troop.

"Okay, let’s go! Let’s go!’’ I tell him.

"All right! All right!’’ says Herbie, jumping.

What am I going to do?

Rogo, (I’m telling myself in my head), you loser! You can’t even manage a troop of Boy Scouts! Up front, you’ve got some kid who wants to set a speed record. and here you are stuck behind Fat Herbie, the slowest kid in the woods. After an hour, the kid in front—if he’s really moving at three miles per hour—is going to be two miles ahead. Which means you’re going to have to run two miles to catch up with him.

If this were my plant, Peach wouldn’t even give me three months. I’d already be on the street by now. The demand was for us to cover ten miles in five hours, and we’ve only done half of that. Inventory is racing out of sight. The carrying costs on that inventory would be rising. We’d be ruining the company.

But there really isn’t much I can do about Herbie. Maybe I could put him someplace else in the line, but he’s not going to move any faster. So it wouldn’t make any difference.

Or would it?

"HEY!’’ I yell forward. "TELL THE KID AT THE FRONT TO STOP WHERE HE IS!’’

The boys relay the call up to the front of the column.

"EVERYBODY STAY IN LINE UNTIL WE CATCH UP!’’ I yell. "DON’T LOSE YOUR PLACE IN THE LINE!’’

Fifteen minutes later, the troop is standing in condensed line. I find that Andy is the one who usurped the role of leader. I remind them all to stay in exactly the same place they had when we were walking.

"Okay,’’ I say. "Everybody join hands.’’

They all look at each other.

"Come on! Just do it!’’ I tell them. "And don’t let go.’’

Then I take Herbie by the hand and, as if I’m dragging a chain, I go up the trail, snaking past the entire line. Hand in hand, the rest of the troop follows. I pass Andy and keep walking. And when I’m twice the distance of the line-up, I stop. What I’ve done is turn the entire troop around so that the boys have exactly the opposite order they had before.

"Now listen up!’’ I say. "This is the order you’re going to stay in until we reach where we’re going. Understood? Nobody passes anybody. Everybody just tries to keep up with the person in front of him. Herbie will lead.’’

Herbie looks shocked and amazed. "Me?’’

Everyone else looks aghast too.

"You want

him

to lead?’’ asks Andy.

"But he’s the slowest one!’’ says another kid.

And I say, "The idea of this hike is not to see who can get there the fastest. The idea is to get there together. We’re not a bunch of individuals out here. We’re a team. And the team does not arrive in camp until all of us arrive in camp.’’

So we start off again. And it works. No kidding. Everybody stays together behind Herbie. I’ve gone to the back of the line so I can keep tabs, and I keep waiting for the gaps to appear, but they don’t. In the middle of the line I see someone pause to adjust his pack straps. But as soon as he starts again, we all walk just a little faster and we’re caught up. Nobody’s out of breath. What a difference!

Of course, it isn’t long before the fast kids in the back of the line start their grumbling.

"Hey, Herpes!’’ yells one of them. "I’m going to sleep back here. Can’t you speed it up a little?’’

"He’s doing the best he can,’’ says the kid behind Herbie, "so lay off him!’’

"Mr. Rogo, can’t we put somebody faster up front?’’ asks a kid ahead of me.

"Listen, if you guys want to go faster, then you have to figure out a way to let Herbie go faster,’’ I tell them.

It gets quiet for a few minutes.

Then one of the kids in the rear says, "Hey, Herbie, what have you got in your pack?’’

"None of your business!’’ says Herbie.

But I say, "Okay, let’s hold up for a minute.’’

Herbie stops and turns around. I tell him to come to the back of the line and take off his pack. As he does, I take the pack from him—and nearly drop it.

"Herbie, this thing weighs a ton,’’ I say. "What have you got in here?’’

"Nothing much,’’ says Herbie.

I open it up and reach in. Out comes a six-pack of soda. Next are some cans of spaghetti. Then come a box of candy bars, a jar of pickles, and two cans of tuna fish. Beneath a rain coat and rubber boots and a bag of tent stakes, I pull out a large iron skillet. And off to the side is an army-surplus collapsible steel shovel.

"Herbie, why did you ever decide to bring all this along?’’ I ask.

He looks abashed. "We’re supposed to be prepared, you know.’’

"Okay, let’s divide this stuff up,’’ I say.

"I can carry it!’’ Herbie insists.

"Herbie, look, you’ve done a great job of lugging this stuff so far. But we have to make you able to move faster,’’ I say. "If we take some of the load off you, you’ll be able to do a better job at the front of the line.’’

Herbie finally seems to understand. Andy takes the iron skillet, and a few of the others pick up a couple of the items I’ve pulled out of the pack. I take most of it and put it into my own pack, because I’m the biggest. Herbie goes back to the head of the line.

Again we start walking. But this time, Herbie can really move. Relieved of most of the weight in his pack, it’s as if he’s walking on air. We’re flying now, doing twice the speed as a troop that we did before. And we still stay together. Inventory is down. Throughput is up.