The Good Rain: Across Time & Terrain in the Pacific Northwest (12 page)

Read The Good Rain: Across Time & Terrain in the Pacific Northwest Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

The official, living link to all this British baggage is Robert Gordon Rogers, the Queen’s representative. I went to spend some time with Mr. Rogers one day when the morning sun guided the blossoms in the Royal Rose Garden into a chorus of color. He lives in a granite castle called Government House, overlooking the strait. The grounds are exquisite,

thirty-five acres of exotic flowers placed around ponds and old-growth evergreens. Mr. Rogers’s personal secretary, a young man with Edwardian hair and flawless manners, had asked me several questions a few days earlier when I set up the interview.

“Eeee-gun?” He puzzled. “How do you spell that?”

“E-g-a-n.”

“I see. The Irish spelling.”

“Yes.”

“Mmmmmm.”

Government House is not open to the public except on New Year’s Eve, when loyal subjects of the Queen are invited to the annual levee. Inside, the red-carpeted entrance hall is 150 feet long. The oak-paneled interior is filled with oil portraits of lesser royalty, while life-size paintings of Her Majesty the Queen and His Royal Highness the Duke of Edinburgh hang on each side of a granite fireplace. There is also a portrait of Mr. Rogers himself, wearing the gold breastplate, sword, and feathered hat of the Windsor garment. On this morning, servants in white uniforms and little headpieces that look like napkins tiptoe back and forth across the immense hall, carrying tea and coffee for Mr. and Mrs. Rogers, who live amidst the hush of elegance and the low hum of servant gossip.

I’m ushered into a private chamber, where I meet the Vice Regal. He seats me, and a servant brings coffee on a silver tray. Mr. Rogers looks a lot like Walter Cronkite: silver hair, slicked back, a neatly trimmed silver mustache, silver eyebrows used as conversational punctuation marks. He’s sixty-eight years old, tall, trim, well manicured; he looks and smells the part. Mr. Rogers is having a typical day, welcoming visiting royalty, in this case the Crown Prince of Thailand and his accompanying swordsmen.

He tells me about his uniform, which is kept in a glass case when not worn on formal occasions such as the opening of Parliament. When fully dressed in the garment, Mr. Rogers is anchored in thirty pounds of formalwear. The gold-braided breastplate alone weighs more than ten pounds.

“It’s quite a load,” he says.

I ask him if all these trappings of royalty seem like a lot of blather for what is basically a ceremonial title. Not so, replies Mr. Rogers; in fact, he is the chief executive officer of the Province of British Columbia. Even though the Canada Act of 1982 gave Canadians full power to amend their own constitution, ultimate authority still, he says, rests with the monarchy. All bills passed by the B.C. legislature must be signed by him to

become law. If he wanted to, he could veto any bill in the name of the Queen.

“However, if I chose to do so, it would set off a constitutional crisis,” he says. No Vice Regal has done such a thing in recent memory.

Mainly, he flies the flag—his official flag, at that, a design of Union Jack melded with the B.C. symbol and topped by a St. Edward’s Crown in proper colors—which is hoisted on the ferry whenever he crosses over to the mainland. And he drinks a lot of tea with a lot of visiting royalty. Upon appointment five years ago, his first guests were the Prince and Princess of Wales.

“Nice chap, Charles,” Mr. Rogers said.

Well, what’s he like?

“Puts his pants on one leg at a time, he does.”

Mr. Rogers is very nice, very polite, within reason. What angers the Vice Regal is a woman in Victoria who does occasional parodies of the Queen for local television. She is not particularly vicious; her likeness to QE-2 is used in a gentle inducement to get viewers to buy certain products.

“It’s an outrage!” says the Honourable Mr. Rogers. “An absolute outrage!”

I ask how Victoria would be different if the boundary had not been drawn at the 49th Parallel. He rolls his eyes. “We’d probably be like Los Angeles,” he says, referring to a place that might as well be West Beirut. American cities, even Seattle, seem big and cold and hostile, overbuilt to accommodate the automobile and the egos of office developers. Victoria, he says with absolute assurance, is the British Eden, the prettiest spot in the Empire.

Late afternoon, back on the American side of the Tweed Curtain on the west shores of San Juan Island. I’m at the edge of a forgotten bay, empty of any visitors on this spring day save a wild turkey rooting through the woods on the hill. The Union Jack flies over an abandoned garrison on this far northwestern isle of America, a place of peace that nearly became a battleground. Here, on the eve of the American Civil War, a battalion of British Royal Marines and a motley crew of American soldiers nearly went at each other in a dispute over a dead pig.

Less than ten thousand people live on the 172 islands of the San Juan archipelago, which bask in the rain shadow in protected waters north of the entrance to Puget Sound. Most of the islands are uninhabited, green

cones which rise from the sea, the tops of a mountain chain submerged when retreating glaciers melted away. For the most part, developers and bridge-builders and clearcutters have been kept away; the islands still look as if they were sketched from a Japanese woodcarving.

At low tide, much of the sea changes to land, and then more than seven hundred islands can be counted. People come here to hide, to find something they can’t find on the mainland, to get religion through solitude. From June till September, nearly every day is perfect, with the 10,778-foot volcano of Mount Baker rising from the tumble of the Cascades to the west, blue herons and bald eagles crowding the skies, killer whales breaching offshore. The water is exceptionally clear, the result of a twice-daily shift-change in tide, when it sweeps north toward the Strait of Georgia, then back south toward the Strait of Juan de Fuca. In some places, the rip tides create white water like rapids on a foaming river. Being is bliss. But then the winters come and the tourists all go home and clouds hang on the horizon and unemployment doubles and the island dweller is left with whatever it is that led him to escape the rest of the world.

This seems an odd place for war. After the Treaty of Washington between America and Great Britain was signed in 1846, it remained unclear which country owned the San Juans. According to the treaty, Britain got everything above the 49th Parallel and all the land “to the middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver’s Island; and thence southerly through the middle of said channel, and of Fuca Straits, to the Pacific Ocean.…” The trouble was that several channels fit this description. No one much cared about the ambiguity, at first. The Hudson’s Bay Company fort at Victoria sent a boatload of 1,300 sheep to San Juan Island, the largest in the chain, and they mingled with a handful of British and American farmers.

Then, on June 14, 1859, a pig owned by a British settler wandered into the potato patch of a particularly cantankerous American farmer named Lyman Cutler. Cutler shot the pig, and the two settlers had hot words, each calling the other a foreign trespasser, each declaring his country would back him in a jurisdictional dispute. Overreacting in the tradition of combat-hungry commanders, U.S. Army Captain William S. Harney sent a platoon of troops to the island to back up Cutler’s right to shoot a British pig in his potato patch. The British responded by dispatching troops of their own. Before long there were more than a thousand armed soldiers facing each other, three ships from the British Royal Navy, and

one howitzer-heavy American vessel on hand, with another due to arrive soon. Nine miles apart, each side set up camp and prepared for war.

But nothing happened. For the next thirteen years, the troops remained at their respective garrisons, in time getting to know each other quite well. The opposing forces held banquets and track meets together, shared whiskey and practical jokes, and in all those years never fired a shot. To kill time, the Royal Marines stationed at English Camp started a formal garden, a beautiful rectangular plot of land where only the finest of traditional English flowers would grow. Seeds came from all over the Empire, arriving on Royal Navy ships with fresh supplies and the implements of battle. The Pig War was eventually settled by the German Kaiser, acting as mediator, who gave the islands to America. The English went back to Victoria, or home.

What is left today at English Camp on the American side of the Tweed Curtain is the rectangular garden, the oddest legacy in one of the oddest troop deployments in the history of the Royal Marines. In the Pig War, the ground was turned to begin life, not to bury it. The roses are just starting to blossom on this spring day, the oak which shaded the soldiers is in full foliage. The air is sweet and salty clean—the air of a formal garden in a wild setting—evoking no sense of remorse or the whispers of the dead, a tribute to what happens when an empire leaves rose bushes and rhododendrons behind as its chief colonial legacy.

Chapter 4

T

HE

L

AST

H

IDEOUT

I

’m looking for Beckey. From peak to valley, from glacier to meadow, from fang to overhang, I hear nothing but talk of Beckey. His name echoes off the salmon-colored granite walls of the North Cascades and rustles through fields of waist-high wildflowers. Faces appear out of a fog, muttering Beckey, Beckey, goddamn Beckey. In the alpine villages on either side of the international border, the barkeeps and mini-mart merchants all know Beckey. They’ve seen him, oh yes. Just yesterday, or was it last week? Don’t tell me about Beckey, son: I knew him before he was a statue. He never stays at sea level any longer than it takes to restock his supplies and slake the demands of his libido. In Marblemount and Mazama and Hope, tough little mountain towns pressed against the vertical edge of the Cascades, Fred Beckey is the rarest form of legend: one who’s still alive.

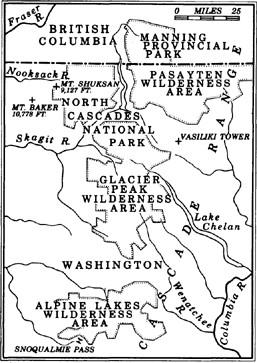

Outside the walls of Beckey’s kingdom, I look up at the sawblade skyline of the North Cascades. These mountains rise from the sea, holding the weight of every storm that blows east off the ocean, delivering an annual dump of 650 inches of snow on the summit barriers. Though uplifted by continental-plate collision and wracked by recent volcanism, the North Cascades owe their surface appearance to water, the master architect of the Northwest. A museum of ice, they are layered with all those low-pressure memories from the Pacific, more than seven hundred living glaciers in all. Think of glaciers, and what comes to mind are slow-moving frozen rivers viewed from the deck of an Alaskan cruise ship. But up here in the folds of the land between Snoqualmie Pass and the Fraser River, the glaciers are in constant and violent downward motion, actively reshaping the land. They crack, roar, scrape and tug, along the way polishing the vertical walls, depositing water in every available bowl, and feeding a forest of evergreens.

Nearly twice the size of Yellowstone National Park, the North Cascades lie within an hour’s drive of four million people. Yet, while the rest of the range, stretching through Oregon and into California, is overrun with visitors, the year-round cannon fire of the north keeps people away from the high country here. Within sight of Seattle and Vancouver are flanks of the earth that have yet to feel a human footprint. Those peaks that have been touched, in all likelihood were first touched by Fred Beckey. Too harsh for prospectors, too high for the casually curious, the North Cascades—one of the last places in mainland America to be fully mapped and explored—have been the domain of the driven.

After crossing over from the lowland warmth of the San Juan Islands, I head east into the mountains, looking for Beckey. He’s supposed to be here, somewhere. The only reason I know this is because Beckey usually migrates in the early summer from the High Sierra of California to the North Cascades of Washington and British Columbia. My first stop is at the Forest Service ranger station in the town of Glacier, deep inside the cedar tunnel of the Mount Baker Highway. Beckey? Sure, everybody knows Beckey, says the ranger. Behind him is a wall-sized map of the North Cascades, an area which William O. Douglas said contained “peaks too numerous to count.” The high points on the map are called Terror, Fury, Despair, Forgotten, Forbidden, Formidable, Freezeout, Inspiration, Triumph, Challenger, Desolation, Isolation, Damnation, Illusion, Joker, Nodoubt, Redoubt, Three Fools. These are not the kind of names that come from dull-witted surveyors or Forest Service committees. These are climbers’ names, many of them Beckey’s, most of them recently coined.

Usually, you can tell a peak that’s been named by Beckey because it has something to do with sex or alcohol. Aphrodite Tower, the Chianti, Burgundy and Pernod Spires—these are Beckey’s peaks.

The forest ranger in Glacier has heard that Beckey is climbing the Nooksack Tower, just south of the Canadian border. Beckey’s got to be getting up there in years, says the ranger. “I remember him from the forties.” Fred Beckey is sixty-five years old, I tell him, same age as Chuck Yeager, the Beckey of the skies. For the last five decades, almost everything he’s climbed has never been climbed before. “Yeah, he’s something, that Beckey,” says the ranger, “but he never checks in with us. If you see the little bastard,” the ranger says, “tell him he’s supposed to get a permit before he crosses Forest Service property into the North Cascade National Park.” Right.