The Good Rain: Across Time & Terrain in the Pacific Northwest (9 page)

Read The Good Rain: Across Time & Terrain in the Pacific Northwest Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

A take-no-prisoners style of logging is used on these six-hundred-year-old trees: all life, from ferns and huckleberry bushes on the ground, to eagles’ nests on the tree crowns, is cut down, bulldozed into garbage heaps, stripped of commercial wood, and then burned. The great, deliberately set fires on state and national forest land are the main cause of air pollution in Seattle and Tacoma during the late summer, as the smoke drifts eastward into the Puget Sound basin and obscures views of the mountains. The giant trees of the peninsula are among the world’s greatest storehouses of carbon. Once they are cut down, and the slash is burned, the fires release enormous amounts of carbon dioxide into the air, contributing in a small way to the greenhouse effect and shortening the planet’s life span. A curious paradox is at work on the forests of the Olympic Peninsula: while the American government scolds Brazil for cutting and burning its tropical rain forest, the Forest Service is aiding and abetting the death of the American rain forest.

My legs move slowly in the deep, wet snow above the Hamma Hamma. The sky is starting to muddy. I’m not a technical climber; I know nothing of the fancy French rock-jock terms or moves, nor can I scale a granite wall. I can use an ice axe to keep from falling in a glacial crevasse, and I have a reasonable idea how to stay out of avalanche gullies. I can read a map. I understand when the sky is trying to tell me something, but like most climbers, amateur and hotdog, I don’t always listen. Most of my life, I’ve stared out at The Brothers from Seattle—a two-breasted beauty that seems to sweep up from the very surface of Puget Sound. From the city, the tips turn pastel in sunset and then dark in silhouette, a very theatrical mountain, almost a custom fit of Winthrop’s description of a peak that, viewed from a seat in civilization, stirs the soul. If ever there was a place where city and wild country could live side by side, this would be it, each needing the other, separated by the moat of Puget Sound. An irony of modern times is that the city dweller is often more appreciative, more protective, of the wild treasure than its rural neighbor. Thus, residents of the Columbia River Gorge fought the legislative protection of a National Scenic Area, and landowners around the Olympic National Park oppose further wilderness designation, just as many of their grandparents were against formation of the park. The larger question for the Northwest, where the cities are barely a hundred years old but contain three-fourths of the population, is whether the wild land can

provide work for those who need it as their source of income without being ruined for those who need it as their source of sanity.

The sky continues to darken. I shift all thoughts to the summit. More than anything, at this instant, I want to stand atop this earthen cloud-grabber. Climbing is not something easily explained. The body gets to working, steaming, ploughing ahead with a single, all-consuming goal in mind. To the east, I can see the Puget Sound basin, wherein lies the Navy base of Bangor, home port for ten Trident submarines, each of which is longer than the Washington Monument is high and carries enough nuclear weapons to vaporize 240 cities. Farther across the water, Seattle can barely be made out. For the ice and rock ahead of me, I could be in the Himalayas, but instead I’m looking straight at a city with thousand-foot-high skyscrapers and ribbons of freeway clogged with traffic. Two hundred inches of precipitation can fall on this mountain, but just across the water Seattle gets less rain than New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Washington and Miami.

Now I come to a rock section too steep to hold the late snow of spring. I put my ice axe behind me, strapped to the pack, and start to clamber up the rock. This must be the last stretch of the mountain, and then I will touch the top and hurry down. But I’m having trouble. I’m slipping, and the way is not clear. Sweat stings my eyes. My fingertips are numb. My knee is shaking against the vertical rock. Only a few feet more, I think, just over the rise. Hold on, hold on … there—but what’s this? I slip back, frightened. A massive white creature with a pair of big, wet eyes, two sharp horns and a full facial beard is staring back at me, not more than five feet away. A ghost. No. He’s clinging … vertically. How? I don’t know. He won’t move. He’s planted there, a two-hundred-pound, snow-white mountain goat. I fall back, startled. My mind was so intent on making this rise—which is not the summit at all—that I blanked everything else out. Now this—an arrogant goat. A warning, perhaps.

The clouds chase me down, spears of rain all around. I slip and slop, making a hasty exit from this high-country home of goats. I think nothing but dark thoughts, of being lost in a storm, buried somewhere, never to be found. Prodded by fear, my heart pounds harder on the way down than it did on the way up. The imagination runs wild. I stop and sit under the overhang of a boulder, shielded from the storm, and try to talk my way down. I have a compass. I know if I continue to descend, I will be in the forest, and then I can follow the runoff to the streams and down to the lake. The mountain goat—poor bastard—his days here are numbered.

Once there were no goats on the Olympic Peninsula. Then, sixty years ago, a dozen of them were introduced as an experiment. Like every other form of life in the Olympics, they flourished, breeding madly, growing to absurd heights, some with pot bellies. Plenty of high-country meadows in the summer and rich valleys in the winter. No hunters. With the gray wolf extinct in these parts, and mountain cougars reduced to a handful, there are no natural predators. Now there are more mountain goats in the Olympics than anywhere else in the country. They tear up the fragile meadows, defoliate the shrubs, and drop large turds in the trickling fresh water of the alpine zone. The goats are cute. Very athletic. Their eyes are big, moist, brown, irresistible. But they are not indigenous, and are making life hard for plants that are, and so the Park Service has decided they must go. At a cost of $1,000 per goat, the rangers are airlifting them out and sending them to goat-deprived areas throughout the West.

The storm has picked up. Visibility about ten feet. Nothing to do but come out from under this rock overhang, wipe the cold rain from my face and slog down. Visiting a tree in a glass cage does have its advantages, but leaves nothing for the storyteller.

Chapter 3

T

OE OF THE

E

MPIRE

O

n the ferry to Vancouver Island, not more than a hundred yards from the international boundary, I look up, and there she is: Her Majesty Elizabeth II, Queen of England, ceremonially smiling under the weight of the Crown. She has a nice smile for a symbol, somewhat more human than a visage on a postage stamp. The Queen is framed in silver, a full-color photograph hanging prominently inside the bow of the ship, overseeing all the sensibly dressed white people. I’m crossing the Tweed Curtain, going from a land of E-Z terms and BBQ to a country full of fellows named Fisswidget, Craigenforth and Hangshaft. On the north coast of Washington, most of the settlements are small and ragged—some with get-to-the-point names like Whiskey Creek or Forks, others remnants from a Salish Indian past all but wiped out, places called Pysht, Sekiu, Sappho, Hoh, Yahoo, Klahowya, Sequim. Nothing regal.

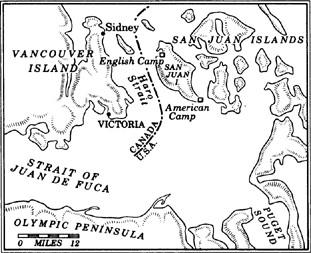

But away from the rain forest, across the swift-moving Strait of Juan de Fuca and up the Gulf Channel, are the mannerly burgs of Sidney and Ladysmith and Victoria, which was the last city in North America to give up the custom of driving on the left-hand side of the road.

At the moment, passengers are queued up for tea on the ferry, Her Majesty now smiling from another picture, this from the boat’s dedication, complete with a tag line not seen on the American side of the Tweed Curtain: G

OD

S

AVE THE

Q

UEEN

. Out the window, three bald eagles are circling for prey near the rock cliffs of an uninhabited island. A covey of harbor seals are crawling over one another on a basaltic perch next to the shore. Shiny red madrona trees stripped of their bark and polished by the wind lean out over the edge. Here and there, groves of Sitka spruce hold to shallow topsoil. The islands are dollops of evergreen that look as if they were plopped in the inland sea like raw dough on a cookie sheet. The rock shore is glacier-carved—lined, furrowed and cracked—a legacy of the last Ice Age, which retreated through here about twelve thousand years ago and carved out Puget Sound and most of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Except for this strange hole of blue sky overhead, it looks like the rest of the Pacific Northwest.

In Victoria, which is neatly sewn into the southern tip of Vancouver Island, they grow cactus; palm trees are conspicuous in front of the several large estates. On the high bluff of the city’s Beacon Hill Park, the old native cedars hold firm, but they are properly manicured, as evenly trimmed as a pensioner’s mustache. On the vast grounds nearby, not a weed is in sight, not a single hawthorn hedge out of place, not a primrose or pansy in less than perfect health. The blossoms are everywhere, crowding ponds inhabited by royal swans (imported from the Queen’s Preserve in Windsor Castle), bordering paths and playfields, all in flawless formation. The minute they start to droop or fade—gone, snipped away lest their sagging remains mar the effect. I wonder: don’t flowers die around here? Archways drip wisterias. Small shrubs are cleanly topped. And near one of these ever-groomed gardens, two teams of eleven gentlemen in matching outfits and funny hats are playing … cricket. Yes, British baseball, with wickets and such. This is tournament play, the scores and details of which will be reported the next day in the Victoria

Times-Colonist

.

As manicured as a fresh-primped poodle, Victoria is the capital of the province of British Columbia, which spreads north in a mostly roadless expanse to the Yukon Territory and east to the plains beyond the Rocky Mountains in Alberta—an area about one-third larger than Texas. Much

of the province briefly entered the American attention span during the presidential campaign of 1844, when “54–40 or Fight” was a slogan of James K. Polk, referring to the latitudinal point where Russian America, now the tip of southeast Alaska, snuggled into British Columbia, or New Caledonia, as it was known before Queen Victoria approved of the present name. Glaciers and wheat farms and forests—the barren, the bounty and the meat of the Canadian West—all are managed from under a pocket of blue sky next to a statue of an overweight Queen.

If the entire Northwest were ever to cleave from the continent and become a nation-state (a suggestion that has already prompted a name for the new country, Ecotopia), it would have not only geography but political sentiment in common. For just as Washington and Oregon were the only states in the West to vote Democratic in the 1988 presidential election, British Columbia went against the tide two weeks later and sent eleven additional members of the liberal New Democratic Party to Parliament. But those new Parliament members are among the harshest critics of the excesses of the American Northwest, which is considered a threat to their way of life. Many British Columbians who look south of the border ask: Why can’t the Americans practice some self-restraint? In perhaps no other place in North America are the character quirks of two nations, one young and wild, the other old and reserved, so evident as here, on either side of the Tweed Curtain. Settling a land of benign extremes, the British reacted cautiously; the Americans never took a breath. The British chose to carve a small patch of perfection from the last unsettled edge of the New World; the Americans went to war against the land.

A visitor from New York City, who came to Victoria more than a century ago, made several observations which are as true now as they were then. He said, “The skies are ever clear, the air is always refreshingly cool, the people look quiet and respectable, and everything is intensely English.” The New Yorker’s only complaint was about Victoria’s women, who “tend toward the ponderous.” So, given the blessings of God and Queen, what have they done with it? Is Victoria a realization of the prophecy of Winthrop—the true city on a hill—the embodiment of a place he thought would emerge from a “climate where being is bliss”? Is this the civilization that would be ennobled by the elements? A land where the totem pole stands next to the statue of the Queen, and the twining of both cultures has produced an offspring of civility?

When Winthrop crossed the Strait of Juan de Fuca, there was no town of Vancouver (which is now the largest city in the Canadian West), just

a Hudson’s Bay Company fort at Langley on the Fraser River, which drains one-fourth of British Columbia. Victoria, by comparison, was a settled character who’d been sitting around the hearth long enough to be bronzed. The only major city on an island the size of Taiwan, Victoria has a metropolitan population of 250,000. Up until 1950, when emigration policies changed, opening the province to more Asian newcomers, more than eighty percent of Victoria’s residents traced their ancestry to Great Britain. Now, only a third are English. Despite repeated admonitions from Canadian government officials, many Victorians still fly the Union Jack every day, fourteen thousand sea miles from the Mother Country.