The Good Rain: Across Time & Terrain in the Pacific Northwest (22 page)

Read The Good Rain: Across Time & Terrain in the Pacific Northwest Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

But instead of being hailed as a model capitalist, Satiacum was shunned by non-Indian business leaders and by many within his own tribe, who distrusted him, comparing the Chief to a mafia don. By the late 1970s, Satiacum’s activities had drawn the attention of the federal government; ever since the Medicine Creek Treaty, the ears of government agents had never been far from the tracks into Indian Country. FBI agents turned an ex-con and Satiacum employee into an informer and wired him. He was sent into Satiacum’s den with instructions that if he could nail the Chief, drug charges against him would be dropped. The feds believed Satiacum was behind several arson fires and attempted shootings of tribal business rivals. The two months their informer spent with Satiacum formed the basis of a sixty-seven-count racketeering indictment filed against him in 1980. Then the IR

S

hit him with $24.7 million in liens against all his property, and the Supreme Court ruled that states could collect taxes on cigarettes sold on reservation land.

Satiacum, the Chief of Chiefs from the lowly, nearly extinct Puyallups, was finished. A jury found him guilty on two counts of racketeering, one of arson, and forty-four of bootlegging cigarettes. By 1982, he was facing a sentence of 225 years in jail, and the movement for self-sufficiency among the Puyallups was dead. On a cold night in December 1982, while out on bail and awaiting sentencing, he said goodbye to his wife and seven children and fled north. He lived for a year on the lam in Canada, until he was arrested by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in Saskatchewan. Dirt-poor, tired and sick, he was thrown in jail. He requested political asylum. After more than three years in British Columbia’s custody, he was granted political refugee status—the first American citizen ever given such designation in Canada. Unlike Joseph of the Nez Perce, the Chief finally found a home in the land of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

While the Chief was on the skids, the lawsuit pursued by his two former cohorts in the Fish War took a dramatic turn. After a three-year trial, Federal Judge George Boldt declared that all the Indians in Puget Sound

who had signed the original 1854 treaties with Stevens were entitled to half the salmon caught in Washington waters. For the first time in their lives, Silas Cross and Bob Satiacum could take fish from the “usual and accustomed grounds” of their ancestors.

My friend Benjamin, who is five years old and loves the woods much as I did as a forty-five-pounder, is going through his Indian phase. In the week the Puyallups were trying to decide what to do with the offer for their land in Tacoma, I went for a walk with Benjamin. He wore his feathered headdress, buckskin pants and moccasins, and carried a bow and arrow. I told him that when I was ten years old I’d wanted to be an Indian and even made plans with a friend to float down the river in our canoe and never come back to the city. We’d just live off the land, hunting deer and fishing and sleeping outside every night and never going back to school. Man, what a life. Benjamin asked me if I’d ever seen a real Indian, and I said yes, lots of times. His face lit up as his mind filled with the images he’d been seeing in all his Indian books. Are they good horse-riders? Did you ever see them spear a whale? Is it true they can split a tree with just a bunch of stone wedges? Could you take me to see an Indian? I started to tell Benjamin that the Indians I knew worked in smoke shops and 7-11s and cinder-block government offices, but he wouldn’t let me finish. He started crying, then kicked me in the leg.

“No! No! No! I want to see a real Indian!”

Driving home from Benjamin’s house, I realized that my perception of the American natives was not all that different from a five-year-old’s. Earlier this summer I had gone looking for the Chief Joseph band of the Nez Perce, but all I’d found was a broken little town in a reservation north of the Grand Coulee Dam. At nine in the morning, I stopped to ask two men for directions to the grave of Chief Joseph, which is the question outsiders almost always ask when they arrive in the arid pine forests of the Colville Reservation in central Washington State. One of the men was clearly drunk; his buddy was on the way. He told me I could drive down to the main junction, where they had a little plaque atop a rockpile in the lot of an abandoned gas station. The inscription said Chief Joseph was buried on this reservation and that he was a military genius who evaded capture for 1,700 miles. But, what about the actual gravesite, I asked. “You can’t see that,” said the second man. Why not? He looked at me coldly, then walked away. Driving through the reservation I saw the worst poverty in the Northwest; homes without electricity or front

doors, rusted cars lying in dried streambeds, emaciated animals prowling through backyard garbage.

When I went to the Warm Springs Reservation in Oregon looking for the horse-riders and fishermen of the inland Columbia River, I found a suicide epidemic. Within a two-month period, seven young tribal members had killed themselves. “It’s so hard to stay alive,” said a Paiute boy of eighteen; two of his brothers had hanged themselves. For most of my life, American Indians have existed only as icons, naturalist heroes of the past; I’m like Benjamin.

The people who took over the Northwest did not treat the Indians any better or worse than other Americans had treated other tribes. Winthrop cast a cold eye on the “fishy siwashes,” as he called them. He was disgusted by their inability to contain themselves after drinking alcohol. But in writing that civilization in the Northwest would be different from any other, more attuned to the land and its influences, Winthrop might as well have been talking about the Indians. They were different from others on this continent, and they still are. The Salish-speaking people along the misted coastline, so wealthy in pre-European times, have now used the lawsuit so effectively they have become role models for the rest of the 1.6 million American Indians. Their efforts have led to a renaissance among some tribes. If old trees are saved because the Nisquallies threaten lawsuits against loggers who damage the salmon watershed, we have them to thank. If Puget Sound is kept free of toxic dumping for the same reason, the tribes are a big part of the reason why.

The aboriginal people of the Pacific Northwest never saw anything like the riches that came to the fallen nations of Japan and Germany after World War II. After all the Indian wars and deceptive treaties, the legalized land-grabbing, the allotment schemes and the assaults of state courts, the tiny nations that lived at river mouths draining the Cascade Mountains were left with nothing but the lawsuit.

And so it was that the non-Indian property owners of Tacoma came to offer $162 million for the land that was supposed to belong to the Puyallups for eternity. If the tribe approves the package, it will be one of the largest Indian land claims in history—second, in this century, to the Alaskan native settlement in 1971. The full moon is well over Commencement Bay, flooding the water in silvery light. All the votes are in. Silas Cross, who runs a small smoke shop and has a satellite dish in his backyard and still farms part of the original allotment given his grandfather, says, “They’re asking us to give up something you can never give up. It’s just another Indian buyout.” But Frank Wright, Jr., doesn’t see

it that way; after nearly 150 years of passive restraint, the Puyallups can now control their destiny, he says. His father, the tireless Fish War leader, cannot lend his voice; he’s too sick to talk. And Bob Satiacum is back in jail, facing charges in Vancouver of having sex with a minor.

If the offer is approved, the Puyallups will get cash, their own deep-water port on Puget Sound—offering them the opportunity to become the first Native American tribe to control a Pacific port—nine hundred acres of tideland, some forest land, a permanent trust fund, and $10 million to rebuild the fishery in the Puyallup River. The river? Why would the Puyallups want anything to do with a limp channel bordered by industrial parasites and sewage-treatment plants? You can’t breathe life back into a body that’s gone cold. Frank Wright, Jr., looks out from the old brick building, beyond the freeway and the smokestacks, and sees a river that one day will bring salmon back to his people. He has no idea what the Puyallup River used to be like, but his father, his body now atrophied from cancer treatment, has told him stories. Plenty of stories.

The vote is 319 to 162 in favor of accepting the offer and dropping the historical claim to the land. A few days later, Frank Wright, Sr., dies of cancer at the age of fifty-nine. By modern standards for the Puyallups, he was an old man.

Chapter 7

F

RIENDS OF THE

H

IDE

A

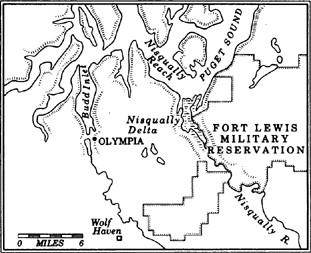

t the Nisqually Delta, where Puget Sound picks up the runoff from one of Mount Rainier’s longest glaciers and then doglegs north, creatures of the air and water have hunkered down for their last stand. It’s an odd place for a sanctuary, this intersection of man and aqua-beast, of freeway and marsh, of fresh water and salt. At the time of Winthrop’s visit, the mouth of the Nisqually served as regional headquarters for the otter- and beaver-hide trade; it was a swap mart for hard-edged men carrying furs to be worn by soft-edged urbanites in distant cities. The fashion designer stood atop the predator chain then.

I come to the Nisqually Delta, not by canoe as did Winthrop, but on an interstate that carries eight lanes of traffic through eighty miles of megalopolis. As the road drops to cross the delta, leaving behind acres of inflatable exurbs and Chuck E.

Cheese pizza palaces, the land turns shaggy and damp, a sudden reappearance of the original form. What used to be the fortress of man, surrounded by wild, has become the fortress of beast, surrounded by city. I find a handful of Nisqually Indians holding to a slice of land along the river, and soldiers playing golf on a bluff once guarded by the Hudson’s Bay Company. The mosaic of salt water and river rush—one of the last true wetlands left on the West Coast—now is a federal wildlife refuge, the animal equivalant of the Indian reservation. Hunters pick off returning loons as they near the Nisqually, but once the birds make it through the firing line to land on the fingers of the river, they find a smorgasbord of food, and federal government protection. The refuge designation came just in time: the Weyerhaeuser Company, owner of 1.7 million acres of timberland in Washington, wanted to build a log-export facility in the Nisqually Delta to help speed the shipment of fresh-cut trees to Japan. When the company backed off during the timber recession of the mid-1980s, conservationists stepped in and saved the delta. However, it may turn out to be wildlife under glass; the county surrounding the delta is the fastest-growing community in the country outside of Florida, and Weyerhaeuser, which calls itself the tree-growing company, plans to build a new city of fourteen thousand people on its acreage bordering the refuge.

A sponge for winter rains, and feasting grounds for species that thrive in the blend of mud and grass, the wetlands in this wet land have always been looked upon as ill-defined and malformed. Not suitable for human habitation, they were judged to be worthless. One by one, the estuaries of the West Coast have been filled in, paved over, planked up. Puget Sound, with more than two thousand miles of inland shoreline, has only a few small places left where river and soil and tide converge to support the bounty of delta life. The Snohomish, outside Everett, has lost three-fourths of its marsh; the Duwamish marsh has disappeared altogether, its tideland filled in with 12 million cubic yards to accommodate Seattle’s early-century expansion. Commencement Bay, where the Puyallup has lost all but a few acres of its wetland cushion, is a toxic nightmare, home of the three-eyed fish and a pulp mill which has been the source of one of the most lasting nicknames in the Northwest—the Aroma of Tacoma. For the last century, oxygen-starved marine life in Commencement Bay has been fed a diet of heavy metals, PCBs and algae.

The Nisqually, for the time being, looks as it did when Winthrop saw it: wide and wet, a stew of shorebirds and marine mammals, more than 240 animal species, with tall grass growing around scattered firs, thick

cottonwoods along the river, and in early summer, waves of pink blossoms from the thorny blackberry bushes. I could set up camp here, as the Nisquallies have for centuries, as Winthrop did overnight, and never need to walk more than a few miles to find every food source necessary to lead a long life. But I don’t need the delta for food.

Walking a trail planked over the mud and eelgrass on a warm summer morning, a day when much of the country is praying for water and trembling about the prospect of global warming, I pass through a window to the air-conditioned wild; with each step, traffic noise gradually recedes and the full-throated sounds of marsh creatures gain. Inside this thousand-acre garrison eagles nest atop box springs of heavy twigs, mallards feast, needle-legged blue herons and big-headed belted kingfishers dive for prey, and assorted others of webbed toe and water-resistant coat hide out for a few weeks. But where are the sea otters? Winthrop found stacks of their furs inside the palisade of Fort Nisqually here. Where are the packs of wolves that howled outside the gates and disrupted his sleep? Where are the whales he dodged while paddling down the length of Puget Sound? Where are the geoducks he called “large, queer clams,” century-old bivalves with necks half as long as a jumprope?