The Good, the Bad and the Unready (23 page)

Read The Good, the Bad and the Unready Online

Authors: Robert Easton

William Shakespeare is to be credited (or blamed) for this nickname. No one called the duke of Lancaster ‘John of Gaunt’ (a corruption of his birthplace of Ghent in Flanders) after he was three years old, but Shakespeare reintroduced the epithet in his play

Richard II

, in which he has John make the famous nationalist speech which ends with the words, ‘This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England’. John of Gaunt, meanwhile, is to be credited (or blamed) for introducing morris dancing to England from Spain.

Emma the

Emma the

Gem of Normandy

Emma, queen of England, d.1052

One of the few portraits of Emma to survive (a self-commissioned work entitled

In Praise of Queen Emma

) depicts a woman with pretty eyes and an attractive oval face. The picture must have been fairly accurate since the French noblewoman garnered not only a unique nickname from an adoring nation but also offers of marriage from two kings.

Her first husband, Ethelred the

UNREADY

, was delighted with his beautiful bride and as a wedding present gave her a large chunk of southern England. Her new subjects were similarly

delighted and called their new queen ‘the Gem of Normandy’. For a while the gem shone brilliantly among her new countrymen. Her popularity dipped but then soared when she was first accused and then cleared both of being an accessory to the murder of her son, Prince Alfred, and of ‘misconduct’ with the bishop of Winchester. Legend has it that she proved her innocence by walking unhurt over nine red-hot ploughshares in Winchester Cathedral. A few years later, however, the gem lost much of her lustre when she fled back to Normandy – some chroniclers say because she was disgusted with her husband’s drunkenness and lawlessness.

Ethelred died in 1016 and the following year Emma regained much of her shine by marrying ‘Canute the Great’ (

see

Great…

BUT NOT THAT GREAT

), with whom she reigned for a further eighteen years.

Nicholas the

Nicholas the

Gendarme of Europe

see

Nicholas the

IRON TSAR

Gloriana

Gloriana

see

GOOD QUEEN BESS

Alexander the

Alexander the

Glorious

Alexander III, king of Scotland, 1241–86

Alexander’s reign began in sad circumstances and ended in tragedy, but the middle years were comparatively glorious. His father, Alexander the Peaceful’, died when Alexander was a boy, and at ten young Alexander found himself married to Margaret, the daughter of Henry III of England. The alliance that this marriage caused was initially an uneasy one, but after some ugly squabbling and sabre-rattling a pact was drawn up that was beneficial to both nations.

With his relationship with England pleasantly cordial, Alexander was able to focus his attention on the north. In 1261 he offered to buy sovereignty of the Hebrides from ‘Haakon the

Old’. Haakon, however, was not selling, and instead of making a deal with Alexander he invaded Scotland, claiming the Isle of Man as well as the Hebrides for himself. Some claim that a Viking, trying to sneak ashore stealthily and catch some Scots by surprise, yelped when he trod on a thistle, thus revealing his whereabouts and securing the thistle’s status as the national emblem of Scotland. The Viking conquest fizzled out, the aged Haakon caught a fever and died, and Alexander was able to purchase all of the Western Isles for a gloriously paltry sum.

A string of personal tragedies then knocked the stuffing out of the king. Alexander’s eldest son died at the tender age of twenty, a second died aged only eight, and his daughter died in childbirth. Finally, while galloping back from a council meeting in Edinburgh, his horse slipped and hurtled off a cliff with him still in the saddle. Alexander and his horse plunged to their deaths; Scotland plunged into a period of bleak and bloody ignominy.

Athelstan the

Athelstan the

Glorious

Athelstan, king of the English, 895–939

Son of Edward the

ELDER

(and, scandal-mongers would have us believe, of a humble shepherd’s daughter to whom Edward had taken a fancy) Athelstan was the first Saxon king of all England. He was tall and handsome, a courageous soldier and an avid collector of art and religious relics who was generous both to his subjects and to the Church. His greatest legacy, however, has to be his judicial reforms. Extant law codes tell of his drive to reduce the punishments meted out to young offenders and also suggest the existence of a corps of skilled scribes – perhaps the beginning of a civil service. His nickname possibly stems from a eulogy by an anonymous German cleric who compares him favourably to the Frankish Charles the

GREAT

: ‘King Athelstan lives,’ he writes, ‘glorious through his deeds!’

Philip the

Philip the

Godless Regent

Philip II, duke of Orleans, 1674–1723

When Philip became regent to the five-year-old Louis the

WELL-BELOVED

, so began one of the most liberal, irreligious and debauched decades in French history. The stifling hypocrisy of the court of Philip’s uncle Louis the

SUN KING

was replaced with a rich mixture of scandal and candour. Banned books were reprinted, the Royal Library was opened to all and tuition fees at the Sorbonne were scrapped.

Philip was a Renaissance man, a talented painter who enjoyed acting in plays by Molière and composing music for opera. As for his ‘godlessness’, there is no doubt. A professed atheist, he celebrated religious feast days by holding orgies at Versailles, and when forced to attend Mass, would read the works of Rabelais hidden inside a Bible. New Orleans, a city not known for its prudishness, was named in his honour.

Albert the

Albert the

Good

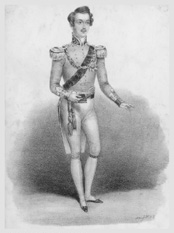

Albert, prince consort of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom, 1819–61

In late November 1861, after a miserably wet day inspecting the buildings for the new military academy at Sandhurst, Albert, the prince consort of Queen Victoria, returned home with a bit of a cold. A few days later, following a visit to Cambridge to admonish his wayward son Edward the

CARESSER

, the cold had developed into something of a severe chill. Within a fortnight he was dead of typhoid fever.

Two years before Albert’s death, the Poet Laureate Alfred Lord Tennyson had dedicated his work

Idylls of the King

to the prince with the lines:

Beyond all titles, and a household name,

Hereafter, thro’ all times, Albert the Good.

And Victoria the

WIDOW OF WINDSOR

was now determined that her late husband should be known as ‘the Good’ because of his modest, gentle devotion, both to his wife and to his adopted country. She accordingly arranged for a number of his speeches to be published, commissioned an immense biography to be written, and impressed Tennyson to join in the hagiographical chorus.

Albert the

Good