The Great American Steamboat Race (25 page)

Read The Great American Steamboat Race Online

Authors: Benton Rain Patterson

Within three minutes the water had reached the upper deck, and passengers there could see from the stern railing people in the river, struggling to stay afloat in the icy stream. Some passengers on the lower deck had been able to save themselves by climbing into the yawl, which they cut loose as the water rose and, finding no oars in it, paddled it to shore with a broom. The only safe place left aboard the vessel was the hurricane deck, but it became difficult to reach as the boat’s bow sank deeper into the river. The only way to get to it was from the stern. Most, if not all, of the passengers that had been in the main cabin, on the boiler deck, managed to reach the roof of the hurricane deck. Some of them were aided by passenger Robert Bullock, a young man from Maysville, Kentucky, who with little regard for his own safety went from stateroom to stateroom and whenever he heard a young child crying he took the child and handed him or her up to someone on the hurricane deck. Among those he helped save was the so-called Ohio Fat Girl, a 440-pound woman who was a member of a carnival troupe.

The powerless vessel, carried downstream by the current, crashed into a second snag, this rising one above the surface. The boat nearly capsized when it struck the snag, tipping over on its larboard side, then lurching to starboard, and spilling a number of passengers into the icy river, only some of whom were able to swim to shore. The boat righted itself and continued to drift downstream, then struck the riverbank so hard that the cabin was separated from the hull. The hull then sank on a sandbar; the cabin continued a short distance and it, too, hit a sandbar and became stuck.

The steamer

Henry Bry

had stopped at Carondelet, just below St. Louis, and as the cabin of the

Shepherdess

floated past its position, the

Henry Bry

’s captain ordered his yawl launched into the river to rescue as many as he and his crewmen could by making repeated trips to haul survivors to safety. The ferryboat

Icelander

came down from St. Louis to join the rescue effort around three

A

.

M

. and removed all the remaining survivors from the

Shepherdess

’s marooned cabin. An estimated forty persons, many of them young children, failed to survive the disaster.

Snags and other objects in the river had been a menace ever since the first steamboat on the Mississippi, the

New Orleans

, had its hull pierced by a stump and sank in 1814. Another early victim was the

Tennessee

. Steaming upriver through a snowstorm, its pilothouse windows coated with snow and its pilot unable to see through them, it ran into a snag near Natchez on the night of February 8, 1823, and had a hole the size of a door torn in its hull. Its yawl was lowered into the water and it took one load of passengers to shore, but with only one oar to propel it, it made just one trip. Many of the passengers and crewmen who were left aboard jumped into the river when they felt the boat going down. Some found floating wreckage to cling to until they could be rescued by skiffs that were rowed out from shore to save them. The rest were not so fortunate. Sixty persons were lost to the river.

The steamer

John L. Avery

left New Orleans on March 7, 1854, and about forty miles below Natchez on March 9, while it was apparently racing another steamer, it struck what was believed to be a tree that had been washed into the river by a recent rain. Water immediately rushed into the boat’s hold through the pierced hull. The boat’s carpenter and J.V. Guthrie, one of the engineers, were standing just forward of the boilers when the crash occurred, and the carpenter dashed to the hold to assay the damage, but the water was pouring in too fast to do anything about the leak, and the carpenter had to quickly retreat back to the deck. Guthrie then hurried for the engine room, but the water was up to his knees before he reached it. The cabin passengers quickly sought refuge on the hurricane deck. Minutes later the hull separated from the cabin and went down in sixty feet of water.

Six persons who had remained in the main cabin were rescued by the captain, J.L. Robertson, and the boat’s two clerks, who lifted them from the rising water through a skylight onto the hurricane deck. One of those pulled through the skylight was a woman with one of her children her arms. She

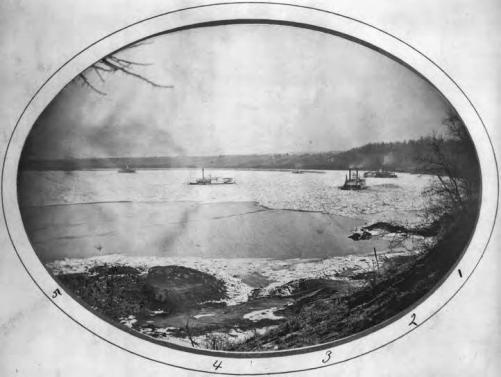

The ice gorge that trapped five steamers in the Mississippi between Cairo, Illinois, and Columbus, Kentucky, in February 1872. Along with explosions, fires, collisions and snags in the river, ice, which could rip open a hull and sink a vessel, was one of the perennial perils for steamers on the upper Mississippi (Library of Congress).

had to be restrained from plunging back into the cabin, nearly filled with water, to rescue her baby, who had been asleep on the woman’s bed. Many of the deck passengers were trapped by freight on the main deck and drowned as the boat sank. The second mate and another person launched the steamer’s yawl, but it was almost immediately turned over by panicked passengers fleeing the doomed vessel. Twelve of the boat’s twenty firemen drowned. Witnesses told of seeing struggling passengers and crewmen in the river, going down one by one in the murky water. At least eighty persons lost their lives in the

John L. Avery

disaster.

On the upper Mississippi ice was a hazard that claimed several steamers, including the

Iron City

, crushed by ice in the river at St. Louis on December 31, 1849; the

Northern Light

, which struck ice along the shore about 1862; the

Fanny Harris,

sunk by ice in 1863; and the

Metropolitan

, sunk by ice at St. Louis on December 16, 1865. Rocks were another peril. The

J.M. Mason

struck a rock that sank it in 1852, and the

H.T. Yeatman

ran into rocks and sank at Hastings, Minnesota, in April 1857. Sandbars were often no worse than a hindrance when steamboats ran onto them, but sometimes they would sink a boat, as one did to the

Kentucky No. 2

, which sank on a sandbar near Prescott, Wisconsin. In some cases the boat that had hit a sandbar was not sunk but simply left hopelessly stranded, unable to be lifted or pulled off, doomed to become a derelict after its passengers and crew had been removed from it.

One of the oddest river hazards was encountered by the steamer

Baltimore

. In 1859 it had the misfortune of running onto the underwater wreck of the steamboat

Badger State

, which had sunk three years earlier. With its hull opened up by the submerged vessel’s superstructure, the

Baltimore

quickly went down, so fast that it settled atop the hulk of the

Badger State

.

Bridges were — and still are — a potential hazard to steamboat navigation. The captain of the modern excursion boat

Mississippi Queen

, replying to a passenger’s question about the worst danger he faced on the river, said it was bridges that presented the biggest concern. If the boat should strike a bridge at a bad angle, there was a great danger that the boat, top heavy as it is, would capsize. The danger posed by bridges has existed since 1856, when the first bridge across the Mississippi River was completed after three years of construction. It was a railroad drawbridge that spanned the river between Rock Island, Illinois, and Davenport, Iowa. It consisted of three parts — a bridge over what is a narrow channel that passes between the Illinois shore and an island in the river (Rock Island), a section of track that ran across the island, and a long bridge over the wider part of the river, between the island and the Iowa shore. The placement of the bridge was disadvantageous for boats, for at that spot, there were cross-currents and boils produced by the chain of rocks in the river, all of which made boat navigation there a pilot’s challenge.

When it was proposed, the bridge met powerful opposition from steamboat interests, who argued that it would be a hazard to navigation, and from the United States secretary of war, Jefferson Davis, who issued a ruling prohibiting its construction on the grounds that it would cross a government reservation. Nevertheless, it was built, the railroad interests proving more powerful than those who opposed the bridge.

On the morning of May 6, 1856, fourteen days after the first train had chugged across the newly completed bridge, the steamer

Effie Afton

passed under the bridge’s draw and when it was some two hundred feet above the bridge, its starboard paddle wheel inexplicably stopped, and the boat turned, swung back and crashed into one of the bridge’s piers. The impact apparently knocked over the stove in the

Effie Afton

’s galley, starting a fire that rapidly spread over the boat, destroying it and a section of the bridge as well. A number of lives were lost.

The

Effie Afton

’s owners swiftly sued the bridge company for damages. Suspecting that sympathy for the steamboat owners and for the

Effie Afton

’s victims would be strong, the directors of the bridge company carefully chose a lawyer who could persuasively argue their case. The man they picked was a forty-seven-year-old lawyer from Sangamon County, Illinois, who had been recommended to them as “one of the best men to state a case forcibly and convincingly, with a personality to appeal to any judge or jury hereabouts.” His name was Abraham Lincoln.

The case went on the docket as Hurd vs. Railroad Bridge Company and was tried before Justice John McLean in Circuit Court in September 1857. Lawyers for the steamboat company presented two main arguments. One, that the Mississippi River was the great waterway for the commerce of the entire Mississippi valley and it could not be legally obstructed by a bridge. And two, the bridge involved in the accident was so situated in the river’s channel at that point that it constituted a peril to all water craft navigating the river and it formed an unnecessary obstruction to navigation.

Lincoln argued that “one man had as good a right to cross a river as another had to sail up or down it.” He asserted that those rights were equal and mutual rights that must be exercised so as not to interfere with each other, like the right to cross a street or highway and the right to pass along it. From the assertion of the right to cross the river, Lincoln moved on to the means of crossing it. Must it always be by canoe or ferry? he asked rhetorically. Must the products of the vast fertile country west of the Mississippi be forever required to stop at the west bank of the river, there to be unloaded from railway cars and transferred to boats, then reloaded onto cars on the east side of the river? The steamboat interests, he argued, ought not to be able to so hinder the nation’s commerce and to stifle the development of the extensive area of the country that lay west of the Mississippi.

Lincoln conceded that the currents at the site of the bridge were problematic, but on the fourteenth day of the trial he presented a model of the

Effie Afton

and used it to show the jury, with the support of witnesses’ testimony, how the accident occurred and to contend that it was the fault of those in command of the

Effie Afton

, that the boat had altered its course from the safe channel in order to pass another steamer, the

Carson

, which was also ascending the river. “The plaintiffs have to establish that the bridge is a material obstruction,” he declared in his closing argument, “and that they have managed their boat with reasonably care and skill.”

The jury apparently did not think the

Effie Afton

’s owners had made the case Lincoln said they must. The jury failed to agree on a verdict and was discharged.

On May 7, 1858, a St. Louis steamboat owner, James Ward, filed a petition in the U.S. District Court of the Southern Division of Iowa asking that the bridge be declared a nuisance and that the court order it removed. The federal district judge, John M. Love, so ordered, but on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court in December 1862 the order was overturned and the bridge was allowed to remain. Complaints about the bridge continued to come from steamboat owners and captains, to the point that in 1866 the United States Congress passed an act requiring the Rock Island bridge to be dismantled and replaced by a new one farther up the river, the cost of which was to be shared by the railroad and the United States government. The new bridge, erected just above Rock Island, was completed in 1872, and the old one was torn down.

Bridge laws enacted by Congress in the 1870s allowed railroads to build bridges at locations specified in the enactments, but the bridges were required to be of a design and style of construction that would avoid serious obstructions to river navigation.

As for the other steamboat perils, a spokesman for the steamboat industry, William C. Reffield, evidently seeking to avoid further regulation, assured the United States secretary of the treasury, “The magnitude and extent of the danger to which passengers in steamboats are exposed, though sufficiently appalling, is comparatively much less than in other modes of transit with which the public have been long familiar.... It will be understood that I allude to the dangers of ordinary navigation [on the seas], and land conveyances by animal power of wheel carriages. In the former case, the whole or greater part of both passengers and crew are frequently lost, and sometimes by the culpable ignorance or folly of the officers in charge, while no one thinks of urging a legislative remedy for this too common catastrophe. In the latter class of cases, should inquiry be made for the number of casualties occurring ... and the results fairly applied to our whole population and travel, the comparatively small number injured or destroyed in steamboats would be a matter of great surprise.”

6

Even so, the steamboat trade publication

Lloyd’s Steamboat Directory

in 1856 listed eighty-seven major disasters that had occurred on western rivers up to that time, many of which had each claimed a hundred or more lives. Also listed were 220 “minor disasters,” as the publication called them. Between 1811, when the first steamboat descended the Mississippi, and 1850, at the midpoint of the golden age of the Mississippi River steamboat, steamboat accidents on the Mississippi killed or injured more than four thousand people.

7

By far the worst catastrophe on the Mississippi, the deadliest maritime disaster in the nation’s history to this day, taking more lives than did the

Titanic

, was the tragic loss of the steamer

Sultana

. It was a large — two hundred and sixty feet long, forty-two feet in the beam — handsome side-wheeler that had been launched at Cincinnati on January 3, 1863. It had been built for Captain Preston Lodwick, owner of three other steamboats, who paid $60,000 for it and who within the first year of the boat’s operation had made more than twice that amount carrying freight and Union troops under contracts with the U.S. government.

It was equipped with four tubular boilers arranged horizontally and parallel to one another. The boilers were of a kind rarely used on the muddy Mississippi, because the mud carried by the river water, which was drawn into the boilers to produce steam, accumulated not in mud drums but in the two dozen five-inch-wide flues (or tubes) inside each boiler, necessitating frequent cleaning of the flues to prevent them from clogging and bursting.

The

Sultana

was built to accommodate seventy-six cabin passengers — the first-class passengers who occupied the staterooms — and three hundred deck passengers. Its legal capacity, then, was three hundred and seventy-six, plus the eighty to eighty-five members of the crew.

The boat’s captain was thirty-four-year-old Cass Mason, who with two partners had bought the

Sultana

from Lodwick for $80,000 on March 7, 1864. Mason had first become a captain after marrying Mary Rowena Dozier, daughter of Captain James Dozier, who owned several steamers, including one named

Rowena

, which Dozier gave Mason to command. Mason apparently decided to use his new position to make a little money on the side by dealing in contraband, at which he was caught red-handed. On a trip downriver the

Rowena

was stopped by a Union gunboat on February 13, 1863, near Island No. 10 in the Mississippi and had its cargo searched. The search revealed a quantity of quinine destined for Tiptonville, Tennessee, then held by Confederate forces, and three thousand pairs of Confederate uniform pants. The gunboat’s commander confiscated the cargo and the

Rowena

, which the U.S. Navy added to its river fleet and which was permanently lost to Dozier when it struck a snag near Cape Girardeau and sank two months after being seized. Mason managed to avoid arrest, but not the wrath of his father-in-law, who refused to have any further business dealings with him.

Since becoming part owner of the

Sultana

, Mason had evidently incurred more financial problems, for by early April 1865 he had sold most of his share in the boat, reducing his interest from three-eighths to one-sixteenth.

On April 9, 1865, the day that General Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to General Grant at Appomattox Court House, the

Sultana

, with a full load of passengers aboard, docked at St. Louis, having just ended its voyage from New Orleans. Three days later it turned around in the river and began its return trip to the Crescent City. It arrived at Cairo about one o’clock the next morning, April 13. While it still lay docked there, on the evening of April 14, John Wilkes Booth shot President Lincoln in Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. The following morning, the same morning that the president died of his wound, the

Sultana

shoved off from the wharf at Cairo and resumed its downriver run.

The

Sultana

arrived at Memphis on the morning of April 16 and departed that same morning, on its way to Vicksburg. Near Vicksburg, at Camp Fisk, a large number of Union soldiers who had been recently released from Confederate prisoner-of-war camps were waiting to be shipped to Camp Chase, Ohio, near Columbus, and Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, near St. Louis, to be mustered out of the Army before being allowed to return to their homes. The U.S. Army would pay five dollars for each enlisted man and ten dollars for each officer to be transported from Vicksburg to those two destinations. Learning about the released POWs, Mason determined to get a boatload of those veterans as passengers on the

Sultana

. They represented a potential boon to him — perhaps a partial solution to his money problems. Moreover, he figured the

Sultana

was entitled to a load of those passengers because it was one of the steamers of the Merchants’ and People’s Line, an organization of independently owned steamboats that had been formed two months earlier and that held U.S. government contracts to transport freight and troops.