The Great American Steamboat Race (26 page)

Read The Great American Steamboat Race Online

Authors: Benton Rain Patterson

No sooner had the

Sultana

docked at Vicksburg than Mason was talking to Lieutenant Colonel Reuben B. Hatch, chief quartermaster for the U.S. Army’s Department of Mississippi, about picking up his share of military passengers when the

Sultana

made its return trip from New Orleans. Hatch assured him the

Sultana

would get some of the troops.

The

Sultana

arrived at New Orleans on April 19. At about ten o’clock in the morning on Friday, April 21, with seventy-five passengers aboard, as well as a hundred live hogs and sixty mules and horses and other cargo, it backed away from the Gravier Street wharf and began its voyage upstream. The river, running high, was swollen with the waters of the usual spring run-off from melting snow and ice in the northern reaches of the Mississippi and its tributaries. In many places it had surged out of its banks and was streaming southward wide, fast and cold.

With ten hours to go before the

Sultana

was scheduled to reach Vicksburg, its chief engineer, Nathan Wintringer, noticed steam escaping from a crack along a seam in one of the boilers of the larboard engine. He decided the

Sultana

could continue on to Vicksburg, but at a slower speed, and that repairs would have to be made at Vicksburg, where the boat had had to undergo boiler repairs once before.

It reached Vicksburg in the late afternoon on April 23, and Wintringer hustled ashore to find R.G. Taylor, a Vicksburg machinist, and have him assay the boiler problem. Taylor obligingly went aboad and upon inspection of the boilers, found a bulge in the seam of the middle larboard boiler. He asked Wintringer why the boiler hadn’t been repaired before the boat left New Orleans (an indication perhaps of the danger he believed the bulge presented). Wintringer replied that the boiler was not leaking when the vessel was at New Orleans.

Captain Mason then entered the conversation and instructed Taylor to fix the bulging seam as quickly as he could. Taylor responded that to do the job right, he would have to replace two of the boiler’s iron sheets and, apparently encountering some resistance, said that if he were not allowed to make the repairs he felt were necessary, he would make no repairs at all. He then turned and strode off the boat.

Right behind him went Wintringer and Mason, explaining their concern over the amount of time that it would take to replace the two sheets and asking Taylor instead to do the best he could within reasonable time constraints. Mason promised Taylor that when the

Sultana

reached St. Louis, he would make the more extensive repairs that Taylor said were needed. But for now, he urged Taylor, for the sake of time, to simply rivet a patch onto the boiler to take care of the leak. Charmer that he was, he at last persuaded Taylor. A metal patch twenty-six by eleven inches and a quarter-inch thick would be applied to the faulty boiler. The patch would be thinner than the iron sheets that formed the boiler, which were one-third of an inch thick. Taylor’s idea was to smooth out the bulge first, then apply the patch. He was talked out of that and instead was asked to attach the patch over the bulge.

Time was the big consideration for Mason. He knew that those released prisoners of war were waiting for transportation, and he was apparently worried that he might lose his share of them if the

Sultana

were delayed too long. Major General Napoleon J.T. Dana, commander of the Army’s Department of Mississippi, had made known that he wanted those veterans returned home as soon as possible, and two steamers, the

Henry Ames

and the

Olive Branch

, had already embarked a load of them and left Vicksburg earlier that day. The

Sultana

had to be repaired quickly, lest all the troops depart by the time lengthy repairs were done. Those potential passengers had become extremely important to Captain Mason.

Mason wasn’t the only one whose mind was on something other than safety and the welfare of the soldiers who were to become passengers. The U.S. Army officers in charge of the arrangements for transporting the men were showing their own lack of good judgment. Despite the availability of other steamers, including the

Lady Gay

, another Merchants’ and People’s Line steamer, which had a greater capacity than the

Sultana

but had been refused any of the soldiers, and the

Pauline Carroll

, which sat virtually empty at the Vicksburg waterfront, all of the estimated 2,400 released soldiers were crammed onto the

Sultana

. First came 398 soldiers who had just been released from the nearby Army hospital. Then came the first trainload, about 570 men. Then came a second trainload, about 400 men. Then came a third trainload, about 800 men. And all the while, despite gentle protests that the

Sultana

was being overloaded and that the

Pauline Carroll

was standing there empty and ready to go, the officers in charge, Army captain George Williams, the U.S. officer in charge of the U.S.-Confederate exchange of prisoners, and Army captain Frederic Speed, temporarily in charge of the released Union prisoners, refused to put any of the men aboard any boat other than the

Sultana

.

Williams claimed that the

Pauline Carroll

had offered a bribe of twenty cents per man to get the former POWs as passengers and for that reason it could not have a single one of them. Besides, he said, “I have been on board [the

Sultana

]. There is plenty of room, and they can all go comfortably.”

The loading continued on into the darkness of April 24, and when all were aboard, the

Sultana

was literally loaded to the gunwales, from stem to stern. A long row of double-decker cots was set up through the center of the saloon to provide beds for the officers. The enlisted men, the great mass of the troops, had at first been assigned sections of the boat according to their units, the men of the Ohio regiments going to the hurricane deck and filling it, the men of the Indiana regiments going to the boiler deck, encircling the cabin, but as the day had worn on and the troops waiting on the wharf mingled with one another, order and control were lost, the rolls becoming confused and the men allowed to claim space aboard the boat wherever they could find it, men from Michigan, Tennessee, Kentucky and Virginia, most in their early twenties, many looking like skeletons from their months of starvation at the Cahaba and Andersonville prison camps, all eager to get home after having survived the ordeals of the war and the camps.

They filled the main deck, they crowded the hurricane deck, they climbed and took over the roof of the texas deck, the mass of their bodies so heavy that William Rowberry, the

Sultana

’s first mate, directed a work party of deckhands to wedge stanchions between the boiler deck and the hurricane deck to prevent the sagging upper decks from collapsing.

To sleep, the troops would have to lie down anywhere they could, on the steps of companionways, beside the engine room, most on the open decks, stretched out like pieces of cordwood beside one another. In the absence of restrooms, they would contort themselves over or under the boat’s rails to relieve themselves.

William Butler, a cotton merchant from Springfield, Illinois, who from the deck of the

Pauline Carroll

watched the third trainload of troops board the

Sultana

, reported the troops’ reaction: “When about one third of the last party that came in had got on board, they made a stop, and the remainder swore they would not go on board. They said they were not going to be packed on the boat like damned hogs, that there was no room for them to lie down, or a place to attend to the calls of nature. There was much indignation felt among them, and among others who went about the boats. Some person on the wharf boat, an officer I presume, ordered them to move forward and they went on board.”

8

About nine o’clock in the evening on April 24 the

Sultana

at last backed away from the Vicksburg wharf and resumed its northward voyage, the men making the best they could of their miserable situation, which must have seemed but an extension of the horrors they had suffered in the prisoner-ofwar camps. Through two nights and two days they endured as the

Sultana

steamed northward toward home.

About one o’clock in the morning of Thursday, April 27, 1865, having loaded aboard enough coal to get it to Cairo, the

Sultana

pulled away from the coaling station at Memphis and again headed upstream, into a particularly dark night and misting rain. All was quiet on the decks, in the saloon and in the staterooms, almost all of the passengers and most of the crew deep in slumber as the lights of Memphis receded and disappeared. About seven miles above Memphis the

Sultana

approached a group of marshy islands called Paddy’s Hen and Chicks. Ordinarily the river at this spot was three miles wide, but now, swollen with floodwaters, it was three times that width, its waters covering both banks.

At one-forty-five the

Sultana

passed one of the Chicks, island No. 41, near the Arkansas side of the river. After that came Fogelman’s Landing. It was now two o’clock.

Suddenly the

Sultana

erupted in a massive explosion, as if struck by a thunderous earthquake, shattering the vessel, blasting a chasm in the superstructure above the boilers, spraying deadly scalding steam over passengers, blowing parts of the upper decks to fragments and shooting them and passengers high into the night sky, toppling the two chimneys, hurling most of the pilothouse from its perch atop the texas, scattering debris and human bodies, many broken and dead, others still alive but gravely injured, into the cold, dark, surging river. Burning coals, blasted from the vessel’s fireboxes,

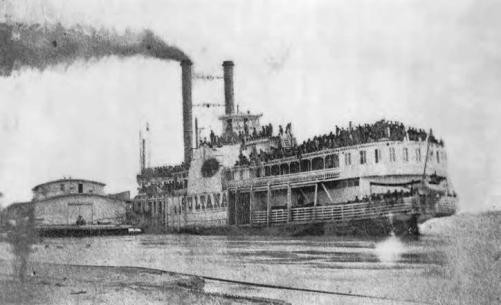

The ill-fated steamer

Sultana

, victim of the worst maritime disaster in U.S. history, photographed at Helena, Arkansas, on April 26, 1865. Early the next morning, as it steamed northward from Memphis, crammed with Union soldiers recently released from Confederate prisoner-of-war camps, it exploded and burned, taking more lives than did the

Titanic

(Library of Congress).

rose like fireworks into the air and rained back down on the wooden decks and superstructure, setting them alight. Within minutes the shattered

Sultana

was engulfed in flames.

From everywhere came the cries, shouts, shrieks and panicked screams of desperate passengers, scalded, burned or critically injured, many trapped beneath wreckage, unable to save themselves or be saved. Soon many hundreds faced the horror of being burned alive or escaping the flames by jumping into the dark and deadly river. Nearly all who were able chose the river. The badly injured and the horribly scalded begged their fellow passengers to lift them and throw them overboard, which some did. The river within yards of the boat quickly became a seething mass of struggling humanity, individuals bobbing so tight together it became impossible for more escaping passengers to leap into the water without landing first on those who had jumped before them. Those unable to swim grasped at anything, anyone within reach, and many went down to their deaths in the frantic grip of each other.

The exact total number of the

Sultana

’s victims remains uncertain, because the number of military passengers aboard is in dispute, as is the number of survivors. Many — perhaps three hundred or more — who were admitted to hospitals and were initially counted as survivors died of their burns or injuries within days after being hospitalized. The estimates of the total number of victims, military and civilian, range from 1,238 (the estimate of Brigadier General William Hoffman, who conducted an inquiry immediately following the disaster) to 1,547 (the estimate made by the U.S. Customs Department at Memphis) to 1,800 or more (calculated from the varied estimates of the number of survivors, which ranged from fewer than 500 to around 800).

9

The likelihood is that the higher estimates of victims are more accurate.

The boat itself, “a massive ball of fire,” as an eyewitness on shore described it, drifted downriver and became lodged against one of the Chick islands near Fogelman’s Landing, just above Mound City, Arkansas. There it sank, its charred remains eventually buried beneath the river’s sediment. In the years since, the river, as if abhorring any reminder of the disaster, shifted its course three miles to the east of Mound City, and the

Sultana

’s grave is now unknown, lying somewhere in an Arkansas farm field.

The cause of the explosion is likewise unknown. An investigation, ordered by Major General Cadwallader C. Washburn, commander of the U.S. Army’s District of West Tennessee, yielded an official report, made public on May 2, 1865, that declared the cause was insufficient water in the boilers. General Dana, commander of the Army’s Department of Mississippi, the man who had ordered the released prisoners sent home as soon as possible, also held an investigation, which, like Washburn’s, had more to do with the overloading of military passengers aboard the

Sultana

than it did with the circumstances of the explosion. On April 30, the U.S. secretary of war, Edwin Stanton, ordered the commissary general of prisoners, Brigadier General William Hoffman, to conduct an additional investigation. Hoffman’s report concluded that there was not enough evidence to establish the cause of the explosion, but that the evidence did suggest that insufficient water in the boilers was the cause.

And there, insofar as the Army was concerned, the matter rested. Claims that Confederate saboteurs had placed explosives aboard the

Sultana

were apparently never seriously considered by the investigators. There is no mention of such in the testimony given to the investigators, and nothing in the investigators’ inquiries indicates sabotage was even suspected.

The relevant civilian authority, J.J. Witzig, the supervising inspector of steamboats for the area that included St. Louis, faulted the patch riveted onto the leaking boiler and put the blame for allowing it on the

Sultana

’s chief engineer, Nathan Wintringer. Witzig, however, conceded that the tubular boilers were part of the problem.

In the end, no one was held accountable for the

Sultana

disaster. The guilt was eventually assigned to the design of the boilers. After the

Walter R. Carter

, equipped with tubular boilers like the

Sultana

’s, blew up later in 1865, killing eighteen people, and the

Missouri

, similarly equipped, exploded the next year, killing seven, the offending boilers were removed from all steamers traveling south of Cairo.