The Great American Steamboat Race (30 page)

Read The Great American Steamboat Race Online

Authors: Benton Rain Patterson

St. Louis Republican

issued terse reports on the race from his perspective :

G

RAND

T

OWER

, July 4, 1:50

A

.

M

.— The R.E. Lee is now passing at speed unprecedented within the memory of the oldest inhabitant.

2:08

A

.

M

.— The Lee is out of sight, abreast of Devil’s Oven. Nothing has been seen of the Natchez yet.

RAND

T

OWER

, 4:30

A

.

M

.— Fog so dense that no boat can get through it. Nothing heard of Natchez yet.

The fog behind the

Lee

had unpredictably blown away and then had returned, thicker than ever, all to the disadvantage of the

Natchez

. As it remained tied up at Shepherd’s Landing, some of the exhausted crew members took as much rest as they could get. Others took turns standing watch, eager for the first sign that the fog was diminishing. After four hours of idleness, just before five o’clock on the morning of July 4, Captain Leathers, thinking he detected a thinning of the fog, ordered the engine room to crank up the

Natchez

’s engines and get it going again. After moving only a few yards, Leathers could see he was mistaken. The fog had yet to break. He ordered the boat tied up again.

Another hour and a half passed. Now it became clear that the fog was indeed dissipating. As the fog broke up, the

Natchez

started up once more, churning its way out into the middle of channel and steaming northward again. Whatever hope Leathers still had for catching the

Robert E. Lee

must have vanished like the fog when the

Natchez

reached Grand Tower and someone in a small boat rowed out to tell him that the

Lee

had passed Grand Tower at two

A

.

M

. and was six hours ahead of him.

About five o’clock the sun had come up, wiping out the last remnants of the fog, pouring light onto the wooded riverbanks and brightening the summer sky. It was going to be a glorious Independence Day on the river. On board the surging

Robert E. Lee

Captain Cannon, peering far astern, could see no sign of the

Natchez

, no telltale smudges of black smoke rising above the horizon. It was obvious to him that he and the

Lee

were far, far ahead.

Past Ste. Genevieve the

Lee

steamed, past old Fort de Chartres on the Illinois shore. By mid-morning it had passed Herculaneum, moving now at less than full speed, Cannon and his pilots knowing there was no longer need for it. At the Missouri village of Sulphur Springs, passengers aboard the

Lee

could see an excursion train of the Iron Mountain Railroad stopped on the tracks that ran beside the river, its passengers having left the train to stand on the riverbank to await the

Lee

’s arrival and greet it with waving handkerchiefs and cheers as it steamed past them, swiftly headed for the finish line.

• 14•

Celebration in St. Louis

When the

Robert E. Lee

approached the lower end of Jefferson Barracks, more cheers of greeting were shouted across the water by passengers on the steam ferryboat

East St. Louis

, which was tied to the riverbank to provide a reviewing stand for a multitude of spectators. As the

Lee

steamed past Jefferson Barracks it received a three-gun artillery salute from the old Army post, and the

Lee

returned the salute with its signal cannon.

At the northern end of Jefferson Barracks four excursion steamers, filled with celebrants, stood in the river waiting for the

Lee

, and when it appeared, the crowds on the steamers and those on the bluffs above Jefferson Barracks roared their greetings and congratulations. Adding to the tremendous welcome was the excursion train that was now dashing toward St. Louis abreast of the

Lee

, blowing its whistle in ear-splitting salute, as the

Lee

’s pilots repeatedly answered with the steamboat’s whistle, filling the sultry air with sounds of raucous celebration. The cheering mass of spectators along the shore grew thicker as the

Lee

reached Carondelet and proceeded on toward downtown St. Louis. The scene was recorded in an eyewitness account by a reporter for the

St. Louis Democrat

:

Long before the Lee was expected, the people began to assemble on the wharf boat, the steamers and the houses fronting the levee. Every boat was crowded with anxious spectators, men, women and children, all determined to see the boat when she came in....

At ten minutes past 11 o’clock a cry was heard from the crowd standing on the levee at the foot of Market street —“There she comes!”

The cry was caught up by the people on the steamers and wharf boats, and along the whole line of the levee it was passed, and “There she comes!” was heard from Market street to the shot tower. There was a movement of the crowd, and all eyes were turned down the river, but no boat was in sight. Then voices exclaimed, “That’s a sell!” and the people settled down again, watching with anxious eyes for the first faint cloud of smoke that might appear in the distance. A few minutes passed, and the word was given that she was “Coming sure!”

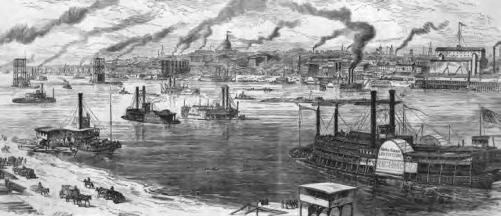

View of the St. Louis riverfront as it appeared in 1871, a year after the race. The

Robert E. Lee

’s arrival on July 4, 1870, was greeted by a cheering mass of spectators along the shore, by passengers on excursion steamers waiting in the river and by the ear-splitting whistle of a train dashing beside the river, abreast of the

Lee

(Library of Congress).

A tug now put out, and proceeded to the foot of Chouteau Avenue, meeting the Lee near that point. At 11:20 the black smoke from the Lee’s chimneys was seen rolling past the foot of Cedar street. A minute later and she shot into view at Market street, and the boom of cannon announced her arrival. The multitude held their breath in eager expectancy, while ever and again the voice of the cannon proclaimed the progress of the victorious steamer. An old colored fireman shouted: “I golly! dat puts me in mind of war times!”

At twenty-five minutes past 11 o’clock the Robert E. Lee passed her place of mooring, at the New Orleans wharf boat, firing a gun as she got opposite. Now the pent-up enthusiasm of the people broke forth in shouts and yells, waving of handkerchiefs and tossing of hats. The salute was returned by those on board the Lee. As she passed we observed two colored men sitting aside the cross-timbers of her jackstaff ; one seemed to be playing the banjo, while the other was yelling at the top of his voice....

The Lee passed on to the head of Bloody Island, where she rounded to. The multitude followed her up the levee, and there was a scene of the wildest confusion — men, women and children hurrying along as in chase of the boat; baggage wagons and hotel coaches dashing through the crowd — people rushing on shore from the steamers and wharf boats, and everybody panting with excitement.

The shouts were not so loud as it was expected they would be from the size of the crowd. The enthusiasm was not so demonstrative as became the importance of the occasion. The colored boatmen, however, made a great deal of noise, some of them yelling at the top of their voices, some falling on the ground and rolling over in the agony of delight.

Slowly the victor backed about, and gracefully moved down stream, then rounded to again and came alongside of the wharf boat, to which she was made fast. Then there was a grand rush on board, and the friends of the officers grasped their hands, and tendered their congratulations.

1

The victorious

Robert E. Lee

had reached its destination at 11:24:30 a.m., and its official time from New Orleans to St. Louis was announced to the cheering crowd on a long, canvas banner tied to the larboard railing on the boat’s boiler deck :

N.O.

TO

S

T

. L

OUIS

, 3

D

., 18

H

. 14

M

The

Lee

had not only beaten the

Natchez

to St. Louis but it had also beaten the record time for a voyage from New Orleans to St. Louis, set by the

Natchez

on June 22, 1870, less than two weeks earlier, by three hours and forty-four minutes.

In New Orleans the feat of the

Robert E. Lee

and its captain and crew was extravagantly heralded on the front page of the

Picayune

, whose readers were informed:

proudly the title of C

HAMPION OF THE

M

ISSISSIPPI

R

IVER

.

Not easily were her honors won, for her rival was swift of keel, and so closely contested the race that it may almost be said she shared the honors with her.

The people of the entire Mississippi Valley have been excited about this race as they never were before by any similar event, and the banks of the great river were thronged with thousands of deeply interested spectators during the progress of the race, all along the route from New Orleans to St. Louis.

It is not to be denied that the illustrious name which the victor bears had much to do with the popular sympathy for her in this contest. To such an extent was this feeling carried that we heard of parties who had their money staked on the Natchez declare they would prefer to lose it rather than the Rob’t E. Lee should be defeated.

2

On reaching downtown St. Louis, Captain Cannon had sped the

Lee

past Walnut Street, where it was to land, and as if taking a victory lap, continued up to where the piers for the new bridge across the Mississippi were under construction, then had made a sweeping turn and headed back to Walnut Street, slowed his vessel and tied it up to the wharf boat there. Once it was tied up, the throng of well-wishers pushed their way onto the boat to congratulate all who were aboard, creating a lively celebration.

“On board the

Lee

,” the

Democrat

’s reporter wrote, “the scene was one the like of which is seldom witnessed. Although the police placed on the steps leading to the cabin were active and determined, such crowds passed up and through the cabin that hardly anything could be heard for the noise arising from the confused movements.”

3

Cannon found himself swamped by the crowd, but managed to push free of the mass of bodies and make his way off the

Lee

and onto the wharf boat, where he was met by the official welcomers, including Captain Nat Green, who led him away from the throng and into a private office to escape the crowd and confusion, which he seemed to tolerate well enough. “He does not seem exhausted by the vigils necessary for the task performed,” the

Democrat

reporter commented. Among the dignitaries on hand to congratulate Cannon were a host of fellow steamboat captains as well as Mary Lee, the thirty-five-year-old daughter of the man for whom the triumphant

Robert E. Lee

had been named, and James B. Eads, designer of St. Louis’s new bridge.

A man of forceful personality and opinions, Eads volunteered to Cannon that he would bet a thousand dollars that if the

Lee

had an iron hull, instead of its wooden hull, it would have made the trip from New Orleans faster by five hours. He told Cannon that an iron hull would have made the

Robert E. Lee

a foot lighter in the water and he then pressed Cannon to tell him how much faster the

Lee

could have gone if its draft had been a foot less. Fortunately for Cannon, another well-wisher was brought to him to be introduced then and he was able to turn away from the argumentive Eads.

Captain Cannon did take time to answer other questions, though. One of his fellow steamboat captains asked him about the stage of water he preferred when attempting a fast trip. Cannon quickly responded, “Bank full of water. I want it bank full, always for my fast trip.”

4

Cannon, the reporter observed, seemed “very happy,” and when asked about his feelings, Cannon replied that if he seemed happy, it was because he had met so many friends and was deeply gratified by the reception given him. Cannon attributed his success to the

Robert E. Lee

’s machinery, calling its engines “the best in the world” and claiming that except for the water leak, the boat’s machinery was in as good condition at the end of the race as it was when the

Lee

left New Orleans. Commenting on the fog that had slowed down the

Lee

and had critically delayed the

Natchez

, Cannon admitted, “Someone aboard was in favor of laying up,” apparently referring to himself, “but I persisted in running slow, and in a few minutes the fog was left behind.”

5

Amid the hubbub, one of the

Lee

’s passengers, feeling effusive over the success of the

Lee

and Captain Cannon’s handling of the vessel, penned a note of gratitude and commendation to him:

We, the undersigned passengers of the Robt. E. Lee, take this method of tendering our thanks to Capt. John W. Cannon and his officers, for the pleasant trip just made, and would compliment Captain Cannon on his superior judgment and skill in the management of his boat, making the time quicker than it was ever made before. And we must say in praise of the noble craft, that everything worked to the satisfaction of all aboard. And we would hardly have known that she was on a fast trip had it not been for the continued cheering that greeted us at every landing as we passed. There was no excitement exhibited by the officers and crew during the whole trip. We would say to those who wish to take a pleasant, safe and speedy trip, to go on the “Robt. E. Lee.”

6

The note’s author then asked his fellow passengers if they would like to sign the statement, and the thirty who affixed their signatures to the note thereby entered their names into the annals of American maritime history, forever identified as participants in the great river’s greatest race.

7

It was almost six o’clock that evening when the

Natchez

came steaming into sight at St. Louis. As it passed Carondelet, steamers standing in the river greeted the

Natchez

with their whistles and bells, and the crowds on shore, standing on the riverbank and on the porches and balconies of houses, shouted and waved handkerchiefs. The crowds in downtown St. Louis, still celebrating the Fourth of July and the conclusion of the historic race, likewise cheered and hailed the late-arriving

Natchez

as loudly and enthusiastically as they had the

Lee

. As his vessel came up to its wharf boat Captain Leathers again pulled his new watch from his pocket and consulted it. It said 5:51 p.m., New Orleans time. The clock on the wharf boat, however, said 6:02, St. Louis time. In either case, the

Natchez

had finished the course some six and a half hours behind the

Robert E. Lee

.

Warmly greeted by a legion of friends, Leathers also faced the newspaper reporters and others in the crowd who had questions for him. He promptly let them know that he believed the

Natchez

had run a faster race than had the

Lee

. He conceded that the

Lee

had arrived six and a half hours before him, but maintained that allowances should be made for the difficulties the

Natchez

had encountered. He said thirty-six minutes should be subtracted from his boat’s running time for the time it lost when it had to stop at Milliken’s Bend for repairs to the valve of its intake pump, and more than six hours should be subtracted for the idle time the

Natchez

had spent waiting for the fog to lift. When all was considered, Leathers figured, the

Natchez

had actually made the trip in twelve minutes less than had the

Robert E. Lee

.

8

Apparently no one in the crowd wanted to argue the matter with the formidable-looking captain of the

Natchez

. “The expression of his countenance,” one newspaperman reported, “is open, frank and rather pleasing. But if anyone is willing to calmly read that face, such a one would very probably conclude that he would not like to have him [Leathers] for an enemy.”

9

To t h e

St. Louis Republican

reporter who had been aboard the

Natchez

all the way from New Orleans and had become one of its champions, Leathers’s argument made perfect sense. “The

Natchez

,” he wrote, “was beaten to St. Louis several hours, yet if an accurate deduction of the time she lost by accident to her pump and also by making two special landings for passengers alone, together with the time lost in the fog and by her numerous backings toward New Orleans from shoal water [were made], it will appear that her real running time to St. Louis is not greater than that of the

R.E. Lee

.”

10

That same reporter, though, decided that the

Natchez

was no faster in the water than was the

Lee

, that they were equal. “The

Natchez

cannot possibly pass the

Lee

under way. She can get just so close as to ride on her swells and not another inch can she gain. The same would be the case with the

Lee

in the wake of the

Natchez

.... Were they let loose at New Orleans together on a big river they both would reach St. Louis in three days and twelve hours from New Orleans.”

11

Captain Leathers, in an interview with a

St. Louis Democrat

reporter the next afternoon, July 5, remained steadfast in his belief that the race had not proved the

Lee

to be the superior vessel:

REPORTER

: “Captain, are you prepared to admit that the Lee is faster than the Natchez?”

LEATHERS

: “No. The Lee is not faster, by a long sight. No, sir.”

REPORTER

: “Any objection to tell me something about your trip?”

LEATHERS

: “No. We went to New Orleans and there were over 90 people’s names on the register for the Natchez and we were to take passengers at Vicksburg, Greenville and Memphis. We had 40 deck and cabin passengers for Cairo, whom we put on boats or tugs, and we brought through to St. Louis about 70 cabin passengers.”

REPORTER

: “How about the Lee?”

LEATHERS

: “She did not land alongside any wharf boat on the river. We lost thirty-six minutes at Buckhorn in Milliken Bend, and put out twenty passengers at Memphis.”

REPORTER

: “Were you as thoroughly stripped as the Lee?”

LEATHERS

: “We did no stripping except of the extra cattle dunnage, and my boat is in perfect order in every particular.”

REPORTER

: “What is the fastest trip you can make from New Orleans to St. Louis?”

LEATHERS

: I can come in 3 days 12 hours; but I am sure not to try it in shoal water. I think the Natchez has the capacity to do it. But for two of my stoppages, I would have beaten the Lee to St. Louis.”

REPORTER

: “Wherein was the Lee’s greatest advantage in this contest?”

LEATHERS

: “She received one hundred cords pine wood off the Pargoud; that was her great aid and advantage, and then I lost six hours in the fog, and the thirty-six minutes I have mentioned before. But for those we would have beaten the Lee’s time to St. Louis some twenty odd minutes. My losing landings were at Buckhorn and Devil’s Island.”

REPORTER

: “Then, as to your preparation for a race, captain?”

LEATHERS

: “I made none. I took fuel at the usual places, and had assistance from nobody. No fuel but Pittsburg coal.”

REPORTER

: “Your passenger receipts must be considerable.”

LEATHERS

: “We had $3000 or $4000 passenger receipts. I wasn’t prepared to tear up my boat, but to carry passengers.”

REPORTER

: “How did you expect to get along above Cairo?”

LEATHERS

: “I expected to clean her out in this river. At Cape Girardeau I was only one hour behind her. I touched bottom twice, having missed the channel twice. We merely bumped, and immediately backed off.”